by Sheila Dunning | Dec 13, 2019

As the migratory birds stop off or stay in the Panhandle this winter, they need to find food, food and more food. There is a wide variety of migration activity in Florida beginning in the fall months of September, October, and November. From woodland song birds to waterfowl to the annual warbler invasion, so many different species show up in Florida. While year-to-year migration patterns and winter foraging grounds can shift for some species due to a variety of reasons, some birds stay in Florida for the winter months of December, January, and February. Some may arrive early and others may stay late.

As the migratory birds stop off or stay in the Panhandle this winter, they need to find food, food and more food. There is a wide variety of migration activity in Florida beginning in the fall months of September, October, and November. From woodland song birds to waterfowl to the annual warbler invasion, so many different species show up in Florida. While year-to-year migration patterns and winter foraging grounds can shift for some species due to a variety of reasons, some birds stay in Florida for the winter months of December, January, and February. Some may arrive early and others may stay late.

Some North American breeding birds endure harsh winters; however, they are physically suited for cold environments in a number of ways. One, they are able to drop their metabolic rate to a near comatose state using very little energy. Two, they are able to position their feathers, or puff up, to trap heat generated by their own body. Others need to head to warmer climates.

Birds migrate for two reasons. Food and weather avoidance. North American breeding birds who nest in the northern part of the continent will migrate south for the winter. As winter approaches, insect and plant life diminishes in the snow-covered states. Migrating birds head south in search of food. Places like Florida are rich in insects, plant life, and nesting grounds.

Birds need high energy food to stay warm. Berry and seed producing plants contain proteins, sugars and lots of fats. Many native trees, shrubs and grasses can aid migratory and winter visiting birds in their relentless search for food. Gardening for birds and other wildlife enables an opportunity for people to experience animals up close, which providing an important habitat in the urban environment.

For more information on which plants are preferred by specific bird species go to: https://www.audubon.org/native-plants

For more information on landscaping for wildlife refer to: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/UW/UW17500.pdf

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 10, 2019

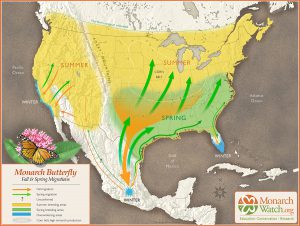

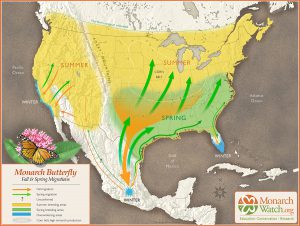

Over 1.8 million Monarch butterflies have been tagged and tracked over the past 27 years. This October these iconic beauties will flutter through the Florida Panhandle on their way to the Oyamel fir forests on 12 mountaintops in central Mexico. Monarch Watch volunteers and citizen scientists will be waiting to record, tag and release the butterflies in hopes of learning more about their migration and what the 2019 population count will be.

Over 1.8 million Monarch butterflies have been tagged and tracked over the past 27 years. This October these iconic beauties will flutter through the Florida Panhandle on their way to the Oyamel fir forests on 12 mountaintops in central Mexico. Monarch Watch volunteers and citizen scientists will be waiting to record, tag and release the butterflies in hopes of learning more about their migration and what the 2019 population count will be.

This spring, scientists from World Wildlife Fund Mexico estimated the population size of the overwintering Monarchs to be 6.05 hectacres of trees covered in orange. As the weather warmed, the butterflies headed north towards Canada (about three weeks early). It’s an impressive 2,000 mile adventure for an animal weighing less than 1 gram. Those butterflies west of the Rocky Mountains headed up California; while the eastern insects traveled over the “corn belt” and into New England. When August brought cooler days, all the Monarchs headed back south.

What the 2018 Monarch Watch data revealed was alarming. The returning eastern Monarch butterfly population had increased by 144 percent, the highest count since 2006. But, the count still represented a decline of  90% from historic levels of the 1990’s. Additionally, the western population plummeted to a record low of 30,000, down from 1.2 million two decades ago. With estimated populations around 42 million, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began the process of deciding whether to list the Monarch butterfly as endangered or threatened in 2014. With the additional information, FWS set a deadline of June 2019 to decide whether to pursue the listing.

90% from historic levels of the 1990’s. Additionally, the western population plummeted to a record low of 30,000, down from 1.2 million two decades ago. With estimated populations around 42 million, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began the process of deciding whether to list the Monarch butterfly as endangered or threatened in 2014. With the additional information, FWS set a deadline of June 2019 to decide whether to pursue the listing.

Scientists estimate that 6 hectacres is the threshold to be out of the immediate danger of migratory collapse. To put things in scale: A single winter storm in January 2002 killed an estimated 500 million Monarchs in their Mexico home. However, with recent changes on the status of the Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has delayed its decision until December 2020. One more year of data may be helpful to monarch conservation efforts.

Individuals can help with the monitoring and restoring the Monarch butterflies habitat. There are two scheduled tagging events in Panhandle, possibly more. St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge is holding their Butterfly Festival on Saturday, October 26 from 10a.m. to 4 p.m. Henderson Beach State Park in Destin will have 200 butterflies to tag and release on Saturday, November from 9 – 11 a.m. Ask around in the local area. There may be more opportunities.

Individuals can help with the monitoring and restoring the Monarch butterflies habitat. There are two scheduled tagging events in Panhandle, possibly more. St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge is holding their Butterfly Festival on Saturday, October 26 from 10a.m. to 4 p.m. Henderson Beach State Park in Destin will have 200 butterflies to tag and release on Saturday, November from 9 – 11 a.m. Ask around in the local area. There may be more opportunities.

There is something more you can do to increase the success of the butterflies along their migratory path – plant more Milkweed (Asclepias spp.). It’s the only plant the Monarch caterpillar will eat. When they leave their hibernation in Mexico around February or March, the adults must find Milkweed all along the path to Canada in order to lay their eggs. Butterflies only live two to six weeks. They must mate and lay eggs along the way in order for the population to continue its flight. Each generation must have Milkweed about every 700 miles. Check with the local nurseries for plants. Though orange is the most common native species, Milkweed comes in many colors and leaf shapes.

by Ray Bodrey | Apr 17, 2019

Soon, two important ecological surveys will begin in Gulf County, concerning both diamondback terrapins and mangroves.

Florida is home to five subspecies of diamondback terrapin, three of which occur exclusively in Florida. Diamondback terrapins live in coastal marshes, tidal creeks, mangroves, and other brackish or estuarine habitats. However, the diamondback terrapin is currently listed as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN).

Diamondback terrapin populations, unfortunately, are nationally in decline. Human activities, such as pollution, land development and crabbing without by-catch reduction devices are often reasons for the decline, but decades ago they were almost hunted to extinction for their tasty meat. The recent decline has raised concern of not only federal agencies, but also organizations and community groups on the state and local levels. Diamondback Terrapin range is thought to have once been all of coastal Florida, including the Keys.

Figure 1: Diamondback Terrapin.

Credit: Rick O’Connor, UF/IFAS Extension & Florida Sea Grant, Escambia County.

Mangroves, a shoreline plant species of south Florida, are migrating north and are now being found in the Panhandle. Both red and black mangroves have been found in St. Joseph Bay. Mangroves establishment could be an important key to a healthy bay ecosystem, as a factor in shoreline restoration and critical aquatic life habitat.

Currently there is a significant data gap for both diamondback terrapin and mangrove populations. Therefore, there is a great need to conduct assessments to learn more about their geographic distribution.

Figure 2. Black Mangrove in St. Joseph Bay.

Credit: Ray Bodrey, UF/IFAS Extension & Florida Sea Grant, Gulf County.

The Forgotten Coast Sea Turtle Center is partnering with UF/IFAS Extension & Florida Sea Grant to assist in surveying and monitoring diamondback terrapins and mangroves in St. Joseph Bay, and we need your help! UF/IFAS Extension & Florida Sea Grant Agent’s Rick O’Connor and Ray Bodrey are providing a training workshop for volunteers and coordinating surveys for St. Joseph Bay. Terrapin surveys require visiting an estuarine location where terrapin nesting sites and mangrove plants are highly probable. Volunteers will visit their assigned locations at least once a week during the months of May and June and complete data sheets for each trip. Each survey takes about two hours, and some locations may require a kayak to reach.

If you are interested in volunteering for these important projects, we will hold a training session on Monday, April 22nd at 1:00 p.m. ET at the Forgotten Coast Sea Turtle Center (located at 1001 10th Street, Port St. Joe).

For more information, please contact:

Ray Bodrey, UF/IFAS Extension Gulf County, Extension Director

rbodrey@ufl.edu

(850) 639-3200

UF/IFAS Extension is an Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 6, 2017

Back in the spring, I wrote an article about the natural history of this ancient animal. However, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) is interested in the status of horseshoe crabs and they need to know locations where they are breeding – and Florida Sea Grant is trying to help.

Horseshoe crabs breeding on the beach.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

If you are not familiar with the horseshoe crab, it is a bizarre looking creature. At first glance, you might mistake it for a stingray. It has the same basic shape and a long spine for a tail. But further observation you would realize it is not a stingray at all.

So then… What is it?

When you find one, most are not comfortable with the idea of picking it up to look closer. The spine is probably dangerous and there are numerous smaller spines on the body. Actually, the long spine in the tail region is not dangerous. It is called a telson and is most often used by the animal to push through the environment when needed, as well as righting itself when upside down. It is on a ball-and-socket joint and if you pick them up, they will swing it around – albeit slowly – but it is of no danger. Note though, do not pick them up by the telson – this can damage them.

If you do try to pick them up with your hands on their sides, you will find they are well armored and have numerous clawed legs on the bottom side. At first, you are thinking it is a crab, and the claws are going to pinch, but again we would be mistaken. The claws are quite harmless – they even tickle when handled. I have held them to allow kids to place their hands in there to feel this. However, when held they will bend their abdomen between 90° and 120°, as if attempting to roll into a ball – which they cannot. At this point, they become difficult to hold. Your hands feel they are in the way and the small spines on the side of the abdomen begin to pierce your skin. So, you flip it on its back. It begins to try a 90° bend in the other direction and begins to swing the telson around. This is probably the most comfortable position for you to hold – but I am not sure what the crab thinks about it.

So, what do you have?

Well, you can see why they call it a crab. It has clawed legs and a hard shell. The body is very segmented. You can also see why it is called a “horseshoe”. But actually, it is not a crab.

Crabs are crustaceans. Crustaceans have two body segments – a head and abdomen, no middle thorax as found on insects. This is the case with the horse crab as well.

Crustaceans have 10-segmented legs, though the claw (cheliped) and swimming paddles (swimmerets) of the blue crab count as “segmented legs”. Horseshoe crabs have 10 as well – seems this IS a crab – but wait…

Crustaceans have two sets of antenna – two short ones and two long – horseshoe crabs do not have any antenna. Traditionally biologists have divided arthropods into two subphyla – those with antenna and those without – so the horseshoe crab is not a crab. It is actually more closely related to spiders, ticks, and scorpions.

Blue crabs are one of the few crabs with swimming appendages.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

It is an ancient animal, fossil horseshoe crabs in this form date back over 440 million years – out dating the dinosaurs. There are four different species of today and there probably were more species in the past. Their range extends from the tropics and temperate coastlines of the planet. Today three of the remaining four species live in Southeast Asia. The fourth, Limulus polyphemus, lives along the eastern and Gulf coast of the United States.

Unfortunately, this neat and ancient creature is becoming rare in some parts of its range. There is a commercial harvest for them. Their blood is actually blue and contains properties beneficially in medicine. Smaller ones are used as bait in the eel fishery, and there is always the classic loss of habitat. These are estuarine creatures and are often found in seagrass and muddy bottom habitats where they forage on bottom dwelling (benthic) animals.

FWC is interested in where horseshoe crabs still breed in our state. Some Sea Grant Agents in the panhandle are assisting by working with locals to report sightings. Sea Grant also has a citizen scientist tagging program to help assess their status. Horseshoe crabs typically breed in the spring and fall during the new and full moons. On those days, they are most likely to lay their eggs along the shoreline during the high tide. This month the full moon is October 5 and the new moon is October 19. We ask locals who live along the coast to search for breeding pairs on October 4-6 and October 18-20 during high tides. If you find breeding pairs, or better yet, animals along the beach laying eggs – please contact your local Sea Grant Agent. We will conduct these surveys in the spring and fall of 2018 and post best search dates at that time.

For more information on the biology of this animal read http://escambia.ifas.ufl.edu/marine/2017/04/10/our-ancient-mariner-the-horseshoe-crab/.

References

Barnes, R.D. 1980. Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders College Publishing. Philadelphia PA. pp 1089.

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Facts About Horseshoe Crabs https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/02/080207135801.htm

Oldest Horseshoe Crab Fossil Found, 445 Million Years Old https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/02/080207135801.htm

by Will Sheftall | Jul 22, 2016

Birds, migration, and climate change. Mix them all together and intuitively, we can imagine an ecological train wreck in the making. Many migratory bird species have seen their numbers plummet over the past half-century – due not to climate change, but to habitat loss in the places they frequent as part of their jet-setting life history.

Migrating songbirds forage for insects in coastal scrub-shrub habitat. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

Now come climate simulation models forecasting more change to come. It will impact the strands of places migrants use as critical habitat. Critical because severe alteration of even one place in a strand can doom a migratory species to failure at completing its life cycle. So what aspect of climate change is now threatening these places, on top of habitat alteration by humans?

It’s the change in weather patterns and sea level that we’re already beginning to see, as the impacts of global warming on Earth’s ocean-atmosphere linkage shift our planetary climate system into higher gear.

For migratory birds, the journey itself is the most perilous link in the life history chain. A migratory songbird is up to 15 times more likely to die in migration than on its wintering or breeding grounds. Headwinds and storms can deplete its energy reserves. Stopover sites for resting and feeding are critical. And here’s where the Big Bend region of Florida figures prominently in the life history of many migratory birds.

According to a study published in March of this year (Lester et al., 2016), field research on St. George Island documented 57 transient species foraging there as they were migrating through in the spring. That number compares favorably with the number of species known to use similar habitat at stopover sites in Mississippi (East Ship Island, Horn Island) as well as other central and western Gulf Coast sites in Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas.

We now can point to published empirical evidence that the eastern Gulf Coast migratory route is used by as many species as other Gulf routes to our west. This confirmation makes conservation of our Big Bend stopover habitat all the more relevant.

The authors of the study observed 711 birds using high-canopy forest and scrub/shrub habitat on St. George Island. Birds were seeking energy replenishment from protein-rich insects, which were reported to be more abundant in those habitats than on primary dunes, or in freshwater marshes and meadows.

So now we know that specific places on our barrier islands that still harbor forests and scrub/shrub habitat are crucial. On privately-owned island property, prime foraging habitat may have been reduced to low-elevation mixed forest that is often too low and wet to be turned into dense clusters of beach houses.

Coastal slash pine forest is vulnerable to sea level rise. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

Think tall slash pines and mid-story oaks slightly ‘upslope’ of marsh and transitional meadow, but ‘downslope’ of the dune scrub that is often cleared for development.

“OK, I get it,” you say. “It’s as if restaurant seating has been reduced and the kitchen staff laid off. Somebody’s not going to get served.” Destruction of forested habitat on our Gulf Coast islands has significantly reduced the amount of critical stopover habitat for birds weary from flying up to 620 miles across the Gulf of Mexico since their last bite to eat.

But why the concern with climate change on top of this familiar story of coastal habitat lost to development? After all, we have conservation lands with natural habitat on St. Vincent, Little St. George, the east end of St. George, and parts of Dog Island and Alligator Point. Shouldn’t these islands be able to withstand the impacts of stronger and/or more frequent coastal storms, and higher seas – and their forested habitat still serve the stopover needs of migratory birds?

Let’s revisit the “low and wet” part of the equation. Coastal forested habitat that’s low and wet – either protected by conservation or too wet to be developed – is in the bull’s eye of sea level rise (SLR), and sooner rather than later.

Using what Lester et al. chose as a reasonably probable scenario within the range of SLR projections for this century – 32 inches, these low-elevation forests and associated freshwater marshes would shrink in extent by 45% before 2100. It could be less; it could be more. Conditions projected for a future date are usually expressed as probable ranges. Experience has proven them too conservative in some cases.

The year 2100 seems far away…but that’s when our kids or grandkids can hope to be enjoying retirement at the beach house we left them. Hmm.

Scientists CAN project with certainty that by the time SLR reaches two meters (six and a half feet) – in whatever future year that occurs, 98% of “low and wet” forested habitat will have transitioned to marsh, and then eroded to tidal flat.

But before we spool out the coming years to a future reality of SLR that has radically changed the coastline we knew, let’s consider where the crucial forested habitat might remain on the barrier islands of the next generation’s retirement years:

It could remain in the higher-elevation yard of your beach house, perhaps, if you saved what remnant of native habitat you could when building it. Or if you landscaped with native trees and shrubs, to restore a patch of natural habitat in your beach house yard.

Migratory songbird stopover habitat saved during beach house construction. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

We’ve all thought that doing these things must be important, but only now is it becoming clear just how important. Who would have thought, “My beach house yard: the island’s last foraging refuge for migratory songbirds!” even in our most apocalyptic imagination?

But what about coastal mainland habitat?

The authors of the March 2016 St. George Island study conclude that, “…adjacent inland forested habitats must be protected from development to increase the probability that forested stopover habitat will be available for migrants despite SLR.” Jim Cox with Tall Timbers Research Station says that, “birds stop at the first point of land they find under unfavorable weather conditions, but also continue to migrate inland when conditions are favorable.”

Migratory birds are fortunate that the St. Marks Refuge protects inland forested habitat just beyond coastal marshland. A longer flight will take them to the leading edge of salty tidal reach. There the beautifully sinuous forest edge lies up against the marsh. This edge – this trailing edge of inland forest – will succumb to tomorrow’s rising seas, however.

Sea level rise will convert coastal slash pine forest to salt marsh. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand, UF IFAS Extension

As the salt boundary moves relentlessly inland, it will run through the Refuge’s coastal buffer of public lands, and eventually knock on the surveyor’s boundary with private lands. All the while adding flight miles to the migration journey.

In today’s climate, migrants exhausted from bucking adverse weather conditions over the Gulf may not have enough energy to fly farther inland in search of forested foraging habitat. Will tomorrow’s climate make adverse Gulf weather more prevalent, and migration more arduous?

Spring migration weather over the Gulf can be expected to change as ocean waters warm and more water vapor is held in a warmer atmosphere. But HOW it will change is difficult to model. Any specific, predictable change to the variability of weather patterns during spring migration is therefore much less certain than SLR.

What will await exhausted and hungry migrants in future decades? Our community decisions about land use should consider this question. Likewise, our personal decisions about private land management – including beach house landscaping. And it’s not too early to begin.

Erik Lovestrand, Sea Grant Agent and County Extension Director in Franklin County, co-authored this article.

by Shep Eubanks | Jul 22, 2016

Photo 1. Large Southern Copperhead in Gadsden County – Photo by Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

There are approximately 44 species of snakes found in Florida. The Southern Copperhead is one of the six venomous snakes that one might encounter while outdoors in the panhandle of Florida. A uniquely beautiful and secretive snake, they historically have only been found in the panhandle counties of Gadsden, Liberty, and Jackson along the Apalachicola River corridor and tributary creeks. Preferred habitat for this species is near streams and wet areas and upland hammocks adjacent to these wet areas. The copperhead is encountered so infrequently in Florida that there have been very few bites and no fatalities reported in Florida from a copperhead bite.

Photo 2. Copper head lying next to a tree in leaf litter demonstrating effective camouflage. Photo by Shep Eubanks – UF/IFAS

Copperheads are pit vipers and are recognizable by the dark brown, hourglass-shaped crossbands along the center of the back. This pattern provides the copperhead with excellent camouflage to blend in with leaves and other litter on the forest floor (see photo 2.). The same snake is pictured in photo 3, crossing a woods road before moving into the swamp edge. This snake is approximately 30 inches long which is the typical size that most adult Southern Copperheads reach.

Photo 3. Typical Southern Copperhead Crossing a Woods Road in Gadsden County. Photo by Shep Eubanks – UF/IFAS

All pit vipers in Florida have venom that is haemotoxic, that is, it destroys the red blood cells and the walls of the blood vessels of the victim. The copperhead venom is not considered to be as potent as the venom of a diamondback rattlesnake.

Copperheads bear live young, typically from 7 to as many as 20 offspring. Young copperheads have identical coloring as the adult except the young snakes have a yellow tip on the tail. The diet of copperheads is the most varied of Florida’s venomous snakes and includes many vertebrates and large insects. They are patient hunters, lying camouflaged in leaves waiting on a meal. Copperheads have been reported to climb trees when cicadas are abundant. The lifespan of a copperhead is estimated to be 20+ years in the wild.

For more information contact your local Extension office and check out these publications: Recognizing Florida’s Venomous Snakes and Florida’s Venomous Snakes.

As the migratory birds stop off or stay in the Panhandle this winter, they need to find food, food and more food. There is a wide variety of migration activity in Florida beginning in the fall months of September, October, and November. From woodland song birds to waterfowl to the annual warbler invasion, so many different species show up in Florida. While year-to-year migration patterns and winter foraging grounds can shift for some species due to a variety of reasons, some birds stay in Florida for the winter months of December, January, and February. Some may arrive early and others may stay late.

As the migratory birds stop off or stay in the Panhandle this winter, they need to find food, food and more food. There is a wide variety of migration activity in Florida beginning in the fall months of September, October, and November. From woodland song birds to waterfowl to the annual warbler invasion, so many different species show up in Florida. While year-to-year migration patterns and winter foraging grounds can shift for some species due to a variety of reasons, some birds stay in Florida for the winter months of December, January, and February. Some may arrive early and others may stay late.