by Kalyn Waters | Apr 29, 2022

Box Turtle. Photo Credit J.D. Willson, University of Georgia

Growing up, or even as an adult there is something exciting about seeing a turtle on the road! We always want to stop and check it out or even help it across. Box Turtles are common in all parts of the southeastern United States. There are four subspecies of box turtles that can be found east of the Mississippi River. Here are three interesting topics about our common box turtles:

Reproduction

With spring in the air and the temperatures rising, they are on the move. There movement is in part due to spring being the beginning of their mating season. In the southeast males and females will mate from spring into the fall. Males will mate with one or multiple females. Amazingly females can lay fertile eggs up to four years following one successful mating! Normal incubation of the eggs typically takes three months.

Lifespan

Box turtles are well developed at birth. As soon as the hatch the start to mature and will grow at a rate of about ½ an inch per year for the first five years. While growth slows dramatically after that, they will continue to grow until they are about 20 years old. It is believed that some box turtles will live to be over 100 years old.

Home Range

While our box turtle friends live a long time, they are homebodies! Their entire home range is typically 250 yards in diameter or less. It is normal to see an overlap of home ranges for box turtles, regardless of sex or age. Keeping in mind the small home range of turtles and their limited ability to travel long distances, you should never pick them up and take them to a new area. If they are crossing a road, only set them to the other side, do not relocate them. In addition, turtles found crossing the roads in June and July are likely pregnant females. These females are likely searching for a nesting site when they are found.

As we move into spring and summer, turtles will become more active. Keep in mind that we should always leave turtles in the wild. They live longer healthier lives and can contribute to their breeding population. Likewise, you should never release a captive turtle into the wild as it will likely not survive and may introduce diseases.

by Laura Tiu | Mar 11, 2022

World Wildlife Day was celebrated on March 3, 2022. This year’s theme is “Recovering key species for ecosystem restoration.” We celebrate this day to bring attention and awareness to many of the plants and animals that are considered threatened and endangered species and highlight efforts to conserve them. It is estimated that over a million species are currently threatened with extinction.

Turkey Creek Niceville, FL (credit E. Zambello)

Florida is considered a very biodiverse state having a great variety ecosystems and unique plants and animals that inhabit these areas. This makes Florida an attractive place to live but can result in increased pollution and land use changes that can be threats to this biodiversity. One local species that experienced this type of pressure is the Okaloosa darter. This tiny 1 to 2 inch fish dwindled to as few as 1,500 individuals surviving when it was declared endangered in 1973. Factors such as its small range, competition from other species, and historical land use practices including artificial impoundments, erosion, and siltation, contributed to its demise.

The Okaloosa darter prefers to live in small, clear, lightly vegetated streams fed by ground water seepage from sand hill areas. This highly specialized habitat is found in only six streams in Okaloosa and Walton Counties and almost exclusively within Eglin Air Force Base’s boundaries. Environmental managers from Eglin Air Force Base partnered with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other agencies and worked diligently to reduce land use impacts and rehab the impaired streams over the past several decades. They reclaimed clay pits near stream headwaters, improved road crossings to reduce sedimentation and enhanced the habitat for the darter.

Okaloosa darter photo credit: FWS.gov

Due to these efforts, the population of Okaloosa Darters has increased to more than 600,000 and the species has now been down listed from endangered to threatened. In fact, the projects have been so successful that the darter is now being considered for delisting as a threatened and endangered species under the Endangered Species Act. This is something to celebrate on this World Wildlife Day as an example of how we can recover key species for ecosystem restoration. The best news is that Eglin Air Force Base’s Jackson Guard Unit is continuing to make on-base conservation a priority, not only for the Okaloosa Darter, but for other plants and animals under their purview.

by Erik Lovestrand | Mar 4, 2022

Many of our local creatures lead fascinating lives that are rarely observed by the casual nature-seeker. However, thanks to those seriously committed naturalists, who may seriously need to be committed, we get the opportunity to peek into the secret lives of newts for some wild revelations. By the way, I do consider myself a naturalist and on occasion will come close to the edge of “crazy” in my nature adventures. Nevertheless, I do not believe I would actually qualify as “committable” because I have never totally lost that innate capacity to be freakishly startled when a treefrog jumps on the back of my neck in the dark. If you ever get past the point of being startled by things like that when on a nighttime herp hunting venture, you should probably speak with a professional.

Several months ago, I once again decided to test my measure of “committability” on a late night visit to the sinkhole pond behind my house. I was hoping to see what kinds of local amphibians might be active because I could hear several different frog species sounding off. As I waded in with my headlamp for a light source, I soon discovered that frogs are pretty darn good at not getting caught at night (imagine that). I had a dip net but never got close enough without scaring the quarry under. However, when I made a few scoops across the bottom in the shallows I was excited to see something wriggling among the leafy debris in the net.

These two “eft-phase” eastern newts were rescued from the authors pool skimmer

Upon returning to the house, it didn’t take long to identify the three-inch long specimen as an eastern newt. As I later read more in depth about this species, I learned that newts are in the family called Salamandridae and typically (not always) have three distinct life phases where they go back and forth between the land and water. After the eggs hatch, larval newts are fully aquatic, with a pair of feathery external gills protruding behind their head. As they mature, they metamorphose into a bright orange/red color and no longer have external gills. They then leave the water for a terrestrial phase where they are called “efts.” Efts may wander the forest floor for many years and travel long distances before once again returning to the water as an adult to breed. Back in the aquatic environment, they morph into a different looking creature yet again. The external gills do not return but the skin color goes from brightly colored to a greenish-yellow and the tail develops a flattened ridge that aids in swimming. All phases have tiny, bright red dots on the body that are circled by black rings, hence their other name, the red-spotted newt. The skin of the eastern newt is also toxic and scientists refer to the bright coloration of the eft as “aposematic” or warning coloration. Their toxicity allows this species to co-exist with fish, unlike some other salamanders that would become tasty snacks and not likely survive to adulthood. The eastern newt is widespread throughout eastern North America and has been intensely studied for its amazing ability to regenerate lost body parts. Not just limbs but even organ tissues!

So the next time you want to test whether or not you might qualify as a hardcore naturalist (i.e. certifiably nuts), take a nighttime trek into a dark, watery, scary place alone. Pay close attention to your reaction when something moves under your foot on the squishy bottom. I would wager that most of you would fall somewhere just shy of being a true hardcore naturalist. I would even put money on it. Have fun!

by Jennifer Bearden | Feb 3, 2022

I routinely receive calls about “failed food plots.” My normal response is to ask about soil testing first. If they performed a soil test and applied fertilizers according to the test, I move on to more questions about the planting methods. I ask what was planted, how was it planted, when was it planted. In some cases, we don’t find the problem even after all these questions. This leads me to my next question: Did you put exclusion cages on your plot?

Exclusion cage in food plot with heavy deer feeding. Photo Credit: Jennifer Bearden

In my experience, I have seen wildlife feed so heavily on the food plot that you think it has failed. This can happen when you have high populations or where non-target animals feed on the plot. In one case, I saw turkeys feeding on newly sprouted plants so heavily that we had “bald spots” in the plot. In another instance, I was called to check a chufa plot that wasn’t performing well. When I arrived at the plot, there were rabbits digging up the chufas and eating them before they sprouted. In the photo here, I am showing heavy deer feeding on a demonstration plot with exclusion cages. Without exclusion cages, I would have assumed a crop failure.

Exclusion cages are simple structures that allow you to see what is growing in the plot versus what the wildlife are eating. They are easy to create and put in place. I use field fence with small openings. I use a piece that is about 5-6 foot long by 3-4 foot high. I roll the fence and make it into a circle that is about 18 inches in diameter. Then, I secure the cage in the plot with landscape staples or rods/posts. I normally install these directly after planting and fertilizing the plot.

Exclusion Cage in food plot with more normal deer feeding. Photo Credit: Jennifer Bearden

Exclusion cages are just another tool to use in evaluating food plot success. These simple tools allow us to see what is growing and compare that to what the wildlife are eating. This allows us to evaluate the food plot. I would also recommend using visual observation. Look for wildlife sign in the food plot. What tracks do you see? Do you see evidence of feeding on the forages? Game cameras are also helpful in determining what wildlife are feeding on the plot. Use your tools wisely to evaluate food plot success each season and adjust accordingly.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 27, 2022

Members of the family Poeciliidae are what many call “livebearers”. Live bearing meaning they do lay eggs as most fish do, but rather give birth to live young. But this is not to be confused with live-bearing you find in mammals – which is different.

Most fish lay eggs. The females and males typically have a courtship ritual that ends with the female’s eggs (roe) being laid on some substrate, or released into the water column, and the male’s sperm (milt) are released over them. Once fertilized the gelatinous covered eggs begin to develop.

Everything the developing young need to survive is provide within the egg. The embryo is suspended in a semi-gelatinous fluid called the amnion. Oxygen and carbon dioxide gas exchange occurs through this amnion and through the gelatinous covering of the egg itself. Food is provided in the form of yolk, which is found in a sac attached to the embryo. There is a second sac, the allantois, where waste is deposited. When the yolk is low and the allantois full – it is time to hatch. This usually occurs in just a few days and often the baby fish (fry) are born with the yolk sac still attached. Parental care is rare, they are usually on their own.

With “livebearers” in the family Poecillidae it is different.

The males have a modified anal fin called a gonopodium. They fertilize the roe not externally but rather internally – more like mammals. The fertilized eggs develop the same as those of other fish. There is a yolk sac and allantois, and the embryo is covered in amnion within the gelatinous egg covering. But these eggs are held WITHIN the female, not laid on the substrate or released into the water column. When they hatch the live fry swim from the mother into the bright new world – hence the term “livebearer”.

There are advantages to this method. The eggs are protected inside the mother, and she obviously provides parental care to her offspring. However, this does make her much slower and an easier target for predators. There is some give and take.

This differs from the “live-bearing” of most mammals in that there is still an egg. Mammals do still have a yolk sac but feeding and removing waste is done THROUGH THE MOTHER. Meaning the embryo is attached to the mother via an umbilical cord where the mother provides food and removes waste trough her placenta. There is no classic egg in this case. I say most mammals because there are two who live in Australia that still do lay eggs – the platypus and the spiny anteater, and the marsupials (kangaroos and opossums) are a little different as well – but marsupials do no lay eggs.

Biologists have terms for these. Oviparous are vertebrates that lay eggs – such as fish, frogs, turtles, and birds. Ovoviviparous are vertebrates that produce eggs but keep them within the mother where they hatch – such as some sharks, some snakes, and the live bearing fish we are talking about here. Then there are the viviparous vertebrates that do not have an egg but rather the embryo is attached, and fed by, the mother herself – like most mammals.

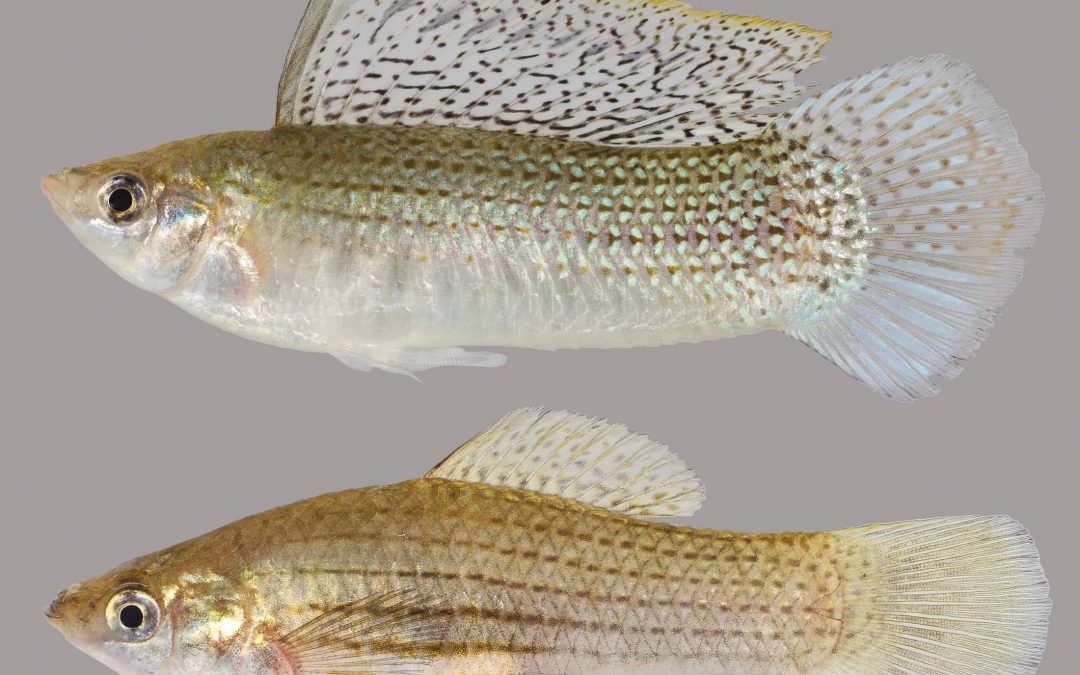

Sailfin Molly. The male is the fish above with the large “sailfin”. Note the gonopodium on his ventral side.

Photo: University of Florida

The livebearers of the family Poeciliidae are ovoviviparous. They are primarily small freshwater fish that are very popular in the aquarium trade. But there are two species that can tolerate saltwater and enter the estuaries of the northern Gulf of Mexico: the sailfin molly and the mosquitofish.

The Sailfin Molly (Poecilia latipinna) is the same fish sold in aquarium stores as the black molly. The black phase is quite common in freshwater habitats, but in the estuarine marshes the fish is more of a gray color with lateral stripes that is made up of a series of dots. They are short-stout bodied fish and the males possess the large sail-like dorsal fin from which the species gets its common name. The females resemble the males albeit no large sailfin and most found are usually round and full of developing eggs. They are very common in local salt marshes and often found in isolated pools within these habitats. The biogeographic range of this species is restricted to the southern United States, reported from South Carolina throughout the Gulf of Mexico. One would guess temperature may be a barrier to their dispersal further north along the Atlantic seaboard.

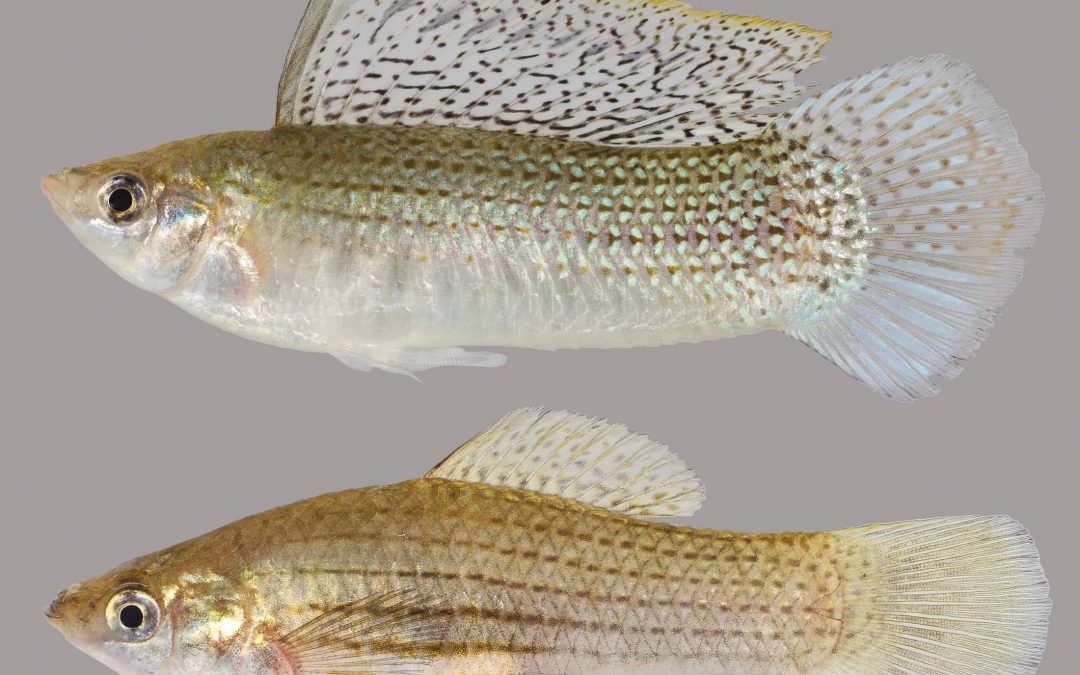

The mosquitofish.

Photo: University of Florida

The Mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) is familiar to many people whether they know it or not. Those who know the fish know they are famous for the habit of consuming mosquito larva and some, including our county mosquito control unit, use them to control these unwanted flying insects. For those who may they are not familiar with it, this is the fish frequently seen in roadside ditches, ephemeral ponds that show up after rainstorms, retention ponds, and other scattered bodies of freshwater within the community. Most who see them call them “minnows”. There is always the question as to “where did they come from?” You have a vacant lot – it rains one day – these small fish show up – where did they come from? The same can be said for community retention ponds. The county comes in a digs a hole – it rains one day, and the retention pond fills – and there are fish in it. One explanation to their source is the movement of fish by wading birds, where the fish incidentally become attached to their feet. Again, they are often released intentionally to help control local mosquito populations. This fish is found in our coastal estuaries but does not seem to like saltwater as well as the sailfin molly. It is found in cooler water ranging throughout the Gulf and as far north as New Jersey.

Both of these fish make excellent aquarium pets, and the sailfin molly in particular can be beautiful to watch.

Reference

Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 20, 2022

When hiking around the Florida panhandle in midwinter, most snakes are undercover trying to avoid the chilly cold fronts that pass through and can drop temperatures close to freezing. So, the probability of seeing one is low. But one species, the eastern garter snake, seems to tolerate cold temperatures better. They are often found basking on open areas this time of year and are quite common not only on the trails, but in our home landscapes as well.

But not to fear…

This is one of the 40 non-venomous snakes found in our state. Many are afraid of these animals because… well… because they are snakes, and that is all that need to be said – at least for some. But for others, they understand the benefits snakes provide to the ecosystem (controlling unwanted pests) and to see one is kind of exciting. Being non-venomous does not mean they will not bite, they certainly will, but no venom is associated with it. Larger non-venomous snake bites can be painful, but not deadly. Garter snake bites barely hurt.

The eastern garter snake is one of the few who are active during the cold months.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Recently my wife and I were on a hike with our grandsons in central Escambia County. At one point my oldest grandson said “snake”. I am not sure how he saw it actually. It was a young eastern garter snake basking in the middle of the trail. These snakes have colorful patterns of stripes and squares that help them blend in well. We knew right away what it was and were all excited to see it. Knowing it was harmless we allowed him to pick it up but warned him that it would most likely bite. Garter snakes tend to flee when first alarmed but will turn and bite if cornered. They will sometimes rattle their tails in the leaves giving off a “buzzing” sound and can release a musk to warn the predator. But this young snake did neither, no rattling, no musk. However, it did try to bite him. After a few photos and the amazement of seeing one, we released it in a sunny spot to continue its midday basking. It was pretty cool.

Many reading this have seen many garter snakes and know this as a harmless animal. They are found all across the state of Florida and much of the eastern United States. There is a subspecies, the blue-striped garter snake, that can be found in the Big Bend area of Florida, but the differences are minor.

Eastern garter snakes are smaller snakes, usually reaching two feet but there is a four-footer on record. They like to inhabit areas that are near water where their favorite prey (amphibians) can be found. Preferring open grassy areas, they can be found in wooded habitats and are often found in lawns and gardens of local neighborhoods.

They hunt primarily during the daylight hours for amphibians but will also eat fish and earthworms. Some have been found to feed on snails, slugs, and even small snakes, birds, and mammals. They are not constrictors but rather grab their prey and swallow it whole.

They are famous for their large gatherings during breeding season. In spring, females will release a pheromone to attract the males, and the males will come, many of them at one time. There are locations in Canada where literally thousands gather at one location. The females do not lay eggs but rather give birth to about 20-30 live young in late summer or fall, it could be up to 100 in a litter. These large groups of slithering garters bring back images from movies where “snake pits” and “a den of snakes” are portrayed. I have never seen such a gathering, and in the southeast, they do not happen in such large numbers as these, but it would be cool.

This time of year, on sunny days in open basking areas, you may see this small but neat snake. The same could be true if hiking near an open sunny location. So, keep your eyes down and maybe you will get lucky.

References

Common Garter Snake. 2021. Florida Snake ID Guide. Florida Museum of Natural History. Common Gartersnake – Florida Snake ID Guide (ufl.edu).

Gibbons, W. 2017. Snakes of the Eastern United States. University of Georgia Press, Athens GA. Pp. 416.

Gibbons, W., Dorcas, M. 2007. Snakes of the Southeast. University of Georgia Press, Athens GA. Pp. 253.