by Mark Mauldin | Sep 2, 2018

A buck chases a doe through plots of wildlife forages being evaluated at the University of Florida’s North Florida Research and Education Center. Photo Courtesy of Holly Ober

I know it feels too hot outside to talk about hunting season or cool-season food plots, but planting time will be here before you know it and now’s the time to start preparing. The recommended planting date for practically all cool-season forage crops in Northwest Florida is October 1 – November 15. Assuming adequate soil moisture, planting during the first half of the range is preferred. Between now and planting time there are several factors that need to be considered and addressed.

Invasive and/or Perennial Weed Control – Deer and other wildlife species utilize many soft/annual “weeds” as forage so controlling them is usually not a major concern. But from time to time unwanted perennials (grasses and woody shrubs) need to be controlled. An unfortunate and all too common example of and unwanted perennial is cogongrass – a highly invasive grass that should always be controlled if found. Effective control of perennial weeds, like cogongrass generally involves the use of herbicides. Late summer/early fall is a very effective time to treat unwanted perennials. Fortunately, this coincides well with the transition between warm-season and cool-season forages. If you have unwanted, perennial weeds in your food plots get them identified now and controlled before you plant your cool-season forages.

Cogongrass shown here with seedheads – more typically seen in the spring. If you suspect you have cogongrass in or around your food plots please consult your UF/IFAS Extension Agent how control options.

Photo credit: Mark Mauldin

Soil Fertility Management – In my experience, the most common cause for poor plant performance in food plots is inadequate soil fertility. Before planting time collect and submit soil samples from each of your food plots. Laboratory analysis of the samples will let you know the fertilizer and lime requirements of the upcoming cool-season crop. It is very important to have the analysis performed prior to planting so performance hindering issues can be prevented. Otherwise, during the growing season, by the time you realize something is wrong, it will likely be too late to effectively address the problem. This is particularly true if the issue is related to soil pH. To affect soil pH in a timely manner lime needs to be incorporated into the soil. Incorporation is impossible after the new crop has been planted. Soil analysis performed at the University of Florida’s Extension Soil Testing Lab cost $7 per sample. Your county’s UF/IFAS Extension Agent can assist you with the collection and submission process as well as help you interpret the results.

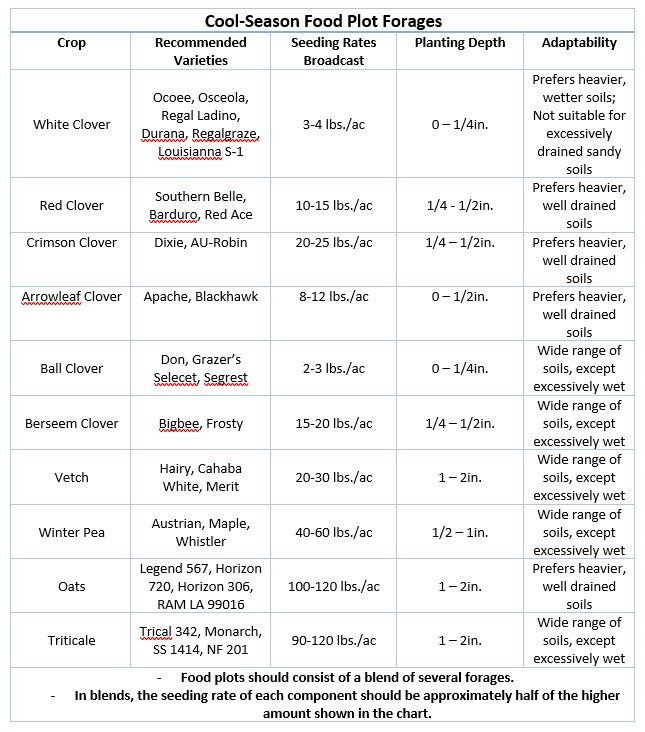

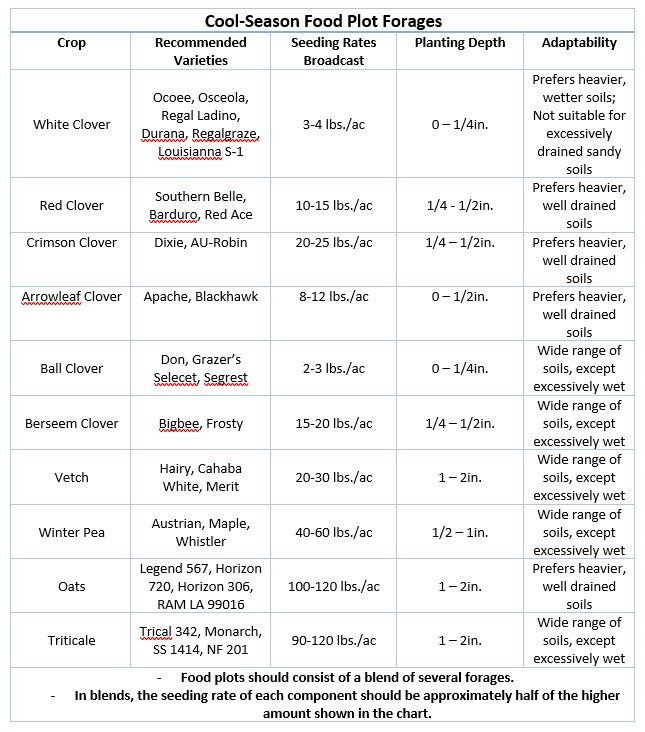

Variety Selection & Seed Sourcing – Sometimes it takes some time to find the best products/varieties. Just because forage seeds are sold locally doesn’t mean that the crop or specific variety is well suited to this area. The high temperatures and disease pressure associated with Florida, even in the “cool-season” mean that many products that do very well in other parts of the country may struggle here. Below are some specific forages that are favored by wildlife (specifically white-tailed deer) and generally well adapted to Florida. You may discover that these varieties are not sitting on the shelf at the local feed & seed. Often local suppliers can get specific varieties, but they must be special ordered, which adds time to the process. Hence the need to start planning and sourcing seed early.

If you are debating trying food plots on your property for the first time, please carefully consider the following. Food plots are not easy – Making productive food plots that provide a measurable, positive impact to the wildlife on your property takes considerable time, effort, and money. Considering this, food plots really only make sense when viewed as habitat improvements that provide long term benefits to multiple wildlife species. If you are looking for nothing more than a deer attractant during hunting season food plots are not a very practical option. For more information on getting started with food plots contact your county’s UF/IFAS Extension Office and check out the reference below.

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 22, 2018

Just a decade ago, few people would have known what a gopher tortoise was and would have hard time finding one. But today, because of the protection they have been afforded by the state, they are becoming more common. This is certainly an animal you might see visiting one of our state parks.

This gopher tortoise was found in the dune fields on a barrier island – an area where they were once found.

Photo: DJ Zemenick

The gopher tortoise is one of only two true land dwelling turtles in our area and is in a family all to its own. They are miners, digging large burrows that can extend up to a depth of 7 feet and a length of 15 feet underground. However, tortoises are not very good at digging up towards the surface, so there is only the one entrance in and out of the burrow. The burrow of the tortoise can be distinguished from other burrowing animals, such as armadillos, in that the bottom line of the opening is flat – a straight line – and the top is domed or arched shaped; mammalian burrows are typically round – circular. Tortoise burrows also possess a layer of dirt tossed in a delta-shaped fan out away from the entrance (called an apron). Many times the soil is from deeper in the ground and has a different color than the soil at the surface. The general rule is one burrow equals one tortoise, though this is not always true. Some burrows are, at times, shared by more than one and some may not be occupied at all. Many field biologists will multiple the number of burrows by 0.6 to get an estimate of how many tortoises there are in the area.

The tortoise itself is rather large, shell lengths reaching 15 inches. They can be distinguished from the other land dwelling turtle, the box turtle, by having a more flattened dome to the shell and large elephant like legs. The forelimbs are more muscular than the hind and possess large claws for digging the burrow. They are much larger than box turtles and do not have hinged plastrons (the shell covering the chest area) and cannot close themselves up within the shell as box turtles can. Tortoises prefer dry sandy soils in areas where it is more open and there are plenty of young plants to eat; box turtles are fans of more dense brush and wooded areas.

Tortoises spend most of the day within their burrows – which remain in the 70°F range. Usually when it is cooler, early morning or late afternoon, or during a rain event – the tortoises will emerge and feed on young plants. You can see the paths they take from their burrows on foraging trips. They feed on different types of plants during different type times of the year to obtain the specific nutrients. There are few predators who can get through the tough shell, but they do have some and so do not remain out for very long. Most people find their burrows, and not the tortoise. You can tell if the burrow has an active tortoise within by the tracks and scrap marks at the entrance. Active burrows are “clean” and not overgrown with weeds and debris. Many times, you can see the face of the tortoise at the entrance, but once they detect you – they will retreat further down. Many times a photo shot within a burrow will reveal the face of a tortoise in the picture. There is a warning here though. Over 370 species of creatures use this burrow to get out of the weather along with the tortoise – one of them is the diamondback rattlesnake. So do not stick your hand or your face into the entrance seeking a tortoise.

Most of the creatures sharing the burrow are insects but there are others such as the gopher frog and the gopher mouse. One interesting member of the burrow family is the Eastern Indigo Snake. This is the largest native snake to North America, reaching a length of eight feet, and is a beautiful iridescent black color. It is often confused with the Southern Black Racer. However, the black racer is not as long, not as large around (girth), and possess a white lower jaw instead of the red-orange colored one of the indigo. The indigo is not dangerous at all, actually it feeds on venomous snakes and it is a good one to have around.

Federal and state laws protect the indigo, as with the gopher frog and mouse. All of these animals have declined in number over the past few decades. This is primarily due to loss of the needed gopher burrows, which have declined because the tortoises have declined, and this is due to habitat loss and harvesting. Again, tortoises like dry sandy soils for digging burrows. They prefer wooded areas that are more open and allow the sun to reach the forest floor where young grasses and flowers can grow. The longleaf pine forest is historically the place to find them but they are found in coastal areas where such open wooded areas exist. The lack of prescribe burning has been a problem for them. Florida is the number one state for lightning strikes. Historically, lightning strikes would occasionally start fires, which would burn the underbrush and allow grasses to grow. In recent years, humans have suppressed such fires, for obvious reasons, and the tortoise community has suffered because of it. Therefore, we now have prescribe fire programs on most public lands in the area. This has helped to increase the number of tortoises in the area and your chance of seeing one.

All of the members of the tortoise community are still protected by state, and – in the case of the indigo snake – federal law, so you must not disturb them if seen. Photos are great and you should feel lucky to have viewed one. Though they could be found anywhere where it is high, dry, and somewhat open – the state and national parks are good places to look.

Reference

Meylan, P.A. (Ed.). 2006. Biology and Conservation of Florida Turtles. Chelonian Research Monographs No. 3, 376 pp.

by Scott Jackson | May 25, 2018

By L. Scott Jackson and Julie B. McConnell, UF/IFAS Extension Bay County

Northwest Florida’s pristine natural world is being threaten by a group of non-native plants and animals known collectively as invasive species. Exotic invasive species originate from other continents and have adverse impacts on our native habitats and species. Many of these problem non-natives have nothing to keep them in check since there’s nothing that eats or preys on them in their “new world”. One of the most problematic and widespread invasive plants we have in our local area is air potato vine.

Air potato vine originated in Asia and Africa. It was brought to Florida in the early 1900s. People moved this plant with them using it for food and traditional medicine. However, raw forms of air potato are toxic and consumption is not recommended. This quick growing vine reproduces from tubers or “potatoes”. The potato drops from the vine and grows into the soil to start new vines. Air potato is especially a problem in disturbed areas like utility easements, which can provide easy entry into forests. Significant tree damage can occur in areas with heavy air potato infestation because vines can entirely cover large trees. Some sources report vine growth rates up to eight inches per day!

Air Potato vines covering native shrubs and trees in Bay County, Florida. (Photo by L. Scott Jackson)

Mechanical removal of vines and potatoes from the soil is one control method. Additionally, herbicides are often used to remediate areas dominated by air potato vine but this runs the risk of affecting non-target plants underneath the vine. A new tool for control was introduced to Florida in 2011, the air potato leaf beetle. Air potato beetle releases have been monitored and evaluated by United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) researchers and scientists for several years.

Air Potato Beetle crawling on leaf stem. Beetles eat leaves curtailing the growth and impact of air potato. (Photo by Julie B. McConnell)

Air potato beetles target only air potato leaves making them a perfect candidate for biological control. Biological controls aid in the management of target invasive species. Complete eradication is not expected, however suppression and reduced spread of air potato vine is realistic.

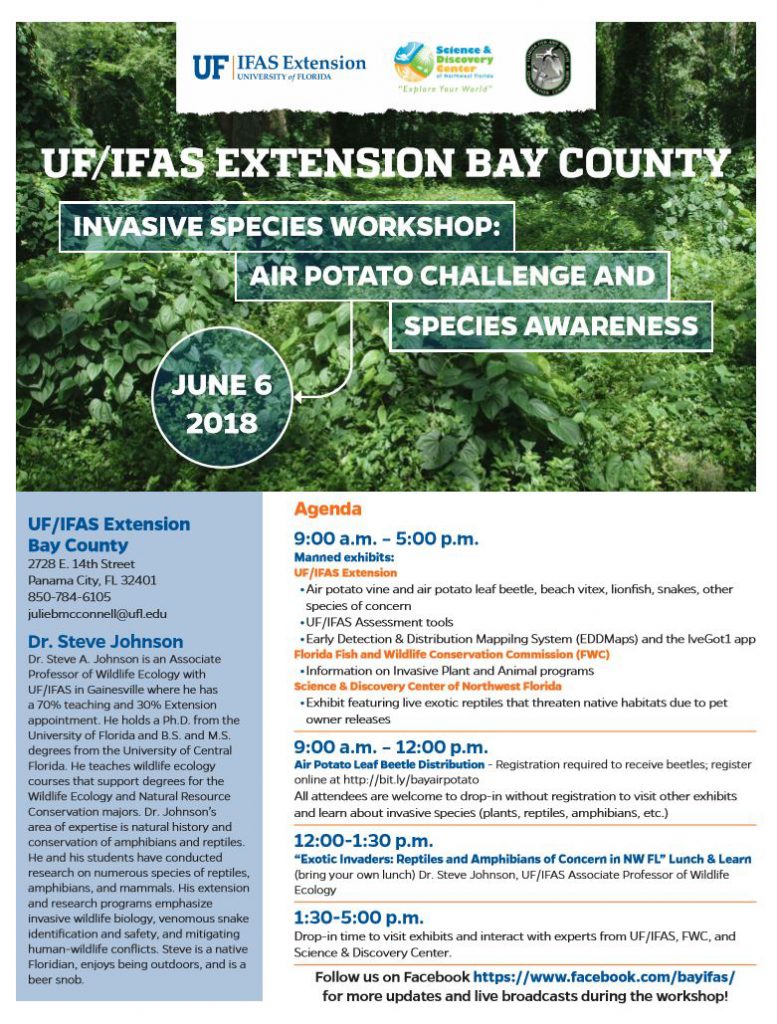

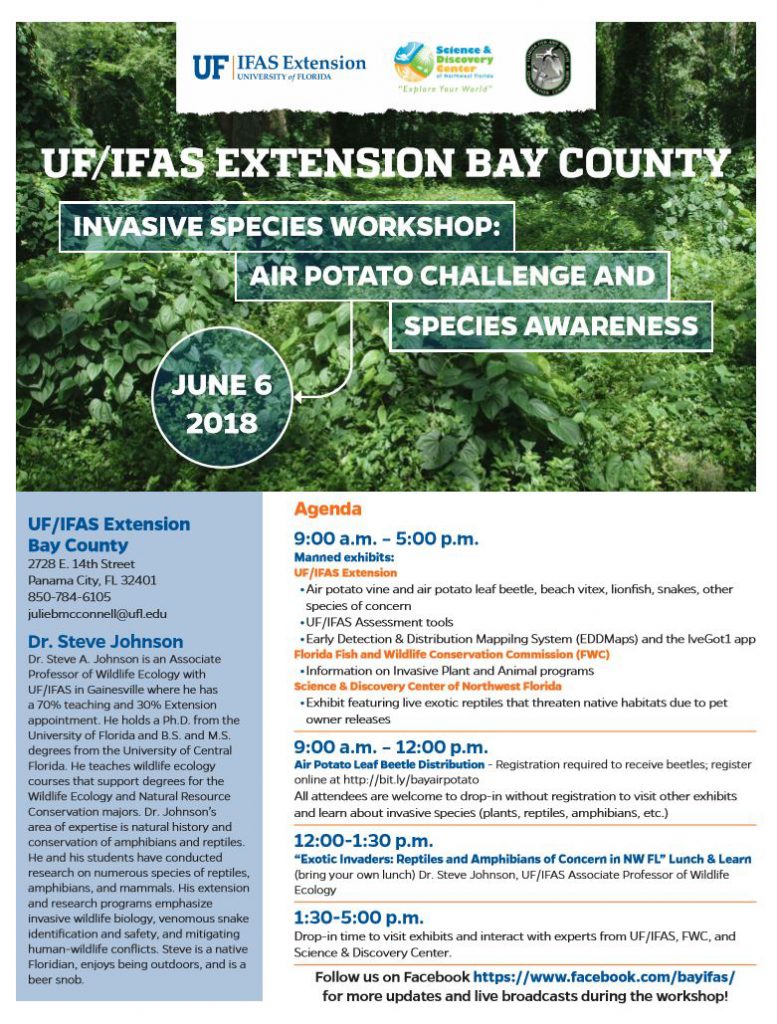

UF/IFAS Extension Bay County will host the Air Potato Challenge on June 6, 2018. Citizen scientist will receive air potato beetles and training regarding introduction of beetles into their private property infested with air potato vine. Pre-registration is recommended to receive the air potato beetles. Please visit http://bit.ly/bayairpotato

In conjunction with the Air Potato Challenge, UF/IFAS Extension Bay County will be hosting an invasive species awareness workshop. Dr. Steve Johnson, UF/IFAS Associate Professor of Wildlife Ecology, will be presenting “Exotic Invaders: Reptiles and Amphibians of Concern in Northwest Florida”. Additionally, experts from UF/IFAS Extension, Florida Fish and Wildlife, and the Science and Discovery center will have live exhibits featuring invasive reptiles, lionfish, and plants. For more information visit http://bay.ifas.ufl.edu or call the UF/IFAS Extension Bay County Office at 850-784-6105.

Flyer for Air Potato Challenge and Invasive Species Workshop June 6 2018

by hollyober | Mar 18, 2018

Bats sometimes move into buildings when they can’t find the natural structures they prefer (caves and large trees with cavities).

All 13 species of bats that live in Florida sleep during the day and feed on insects throughout the night. Most of these bats sleep in natural structures such as trees and caves. But when the natural structures these bats prefer are limited or vandalized, the bats may move into buildings.

Bats are a great help to us. Each of them consumes hundreds of insects per night. Bats save growers billions of dollars annually by reducing insect pests. Some of the pests bats feed on include the damaging fall armyworm, cabbage looper, corn earworm, tobacco budworm, hickory shuckworm, and pecan nut casebearer. But both bats and humans are happier when not sharing living spaces!

If you or someone you know has a group of bats living in a building where they are not welcome, you have options. The safe, humane, effective way to coax a colony of bats out of a building permanently is through a process called an ‘exclusion’. A bat exclusion is a process that prevents bats from returning to a building once they have exited at sunset to feed. This is accomplished by installing a temporary one-way door. This one-way door can take many forms, but the most common is a sheet of plastic mesh screening (with small mesh size of 0.125 x 0.125 inches or less) attached at the top and along both sides of the sheet, and open on the bottom. Another option is to install slick tubes (such as clean caulk tubes) to such entry points. These temporary one-way doors should be attached over each one of the suspected entry/exit points bats are using to get in and out of the building.

It is illegal to harm or kill bats in Florida. However, excluding bats from a building is allowed if you follow practices recommended by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC). According to Florida law, all bat exclusion devices must be left in place for a MINIMUM of 4 consecutive nights with temperatures above 50⁰ F before each entry point can be permanently sealed to prevent bat re-entry. Also, it is unlawful in Florida to attempt to exclude bats from a building between April 15 and August 15, which is bat maternity season. This is when female bats form large colonies and raise young that are unable to fly for their first few weeks of life. If bats were excluded during this time period, young bats (pups) would die indoors.

Bats can be coaxed to leave a building by first identifying the bat’s entry points into the building, and then creating a temporary one-way door using plastic screening with fine mesh size over each of these entry points.

The steps for an effective exclusion are as follows:

- Identify the locations where bats are getting in and out of the building. Look for holes or crevices about the width of your thumb, often near the roofline, with brown staining on the exterior of the building and bat scat (guano, about the size of a grain of rice and brown in color) below.

- Fashion and install one-way doors at each suspected bat entry point. This can be done anytime between August 16 and April 14 – it cannot be done when bats have young pups, which is between April 15 and August 15.

- Leave all one-way doors in place for at least 4 consecutive nights with minimum temperatures above 50⁰ F so all bats leave through the doors and cannot re-enter. If any one-way door becomes ineffective during the 4 day period, begin again. You must be absolutely certain all bats have exited so you do not block any inside the building.

- Immediately after removing the one-way doors, permanently seal each hole to prevent bats from getting back inside.

For detailed instructions on how to conduct a bat exclusion, see this video that features interviews with bat biologists from the University of Florida, FWC, and the Florida Bat Conservancy: How to Get Bats out of a Building.

For additional information on Florida’s bats, visit University of Florida’s bat advice or FWC’s bat website.

Remember, if you have a colony of bats roosting indoors that you want to exclude, you must either act within the next few weeks or else wait until the middle of August to coax them out. Bat maternity season in Florida runs from April 15 to August 15, and during this time no one can attempt to exclude bats from a building.

by Sheila Dunning | Jan 19, 2018

The Florida Master Naturalist Program is an adult education University of Florida/IFAS Extension program. Training will benefit persons interested in learning more about Florida’s environment or wishing to increase their knowledge for use in education programs as volunteers, employees, ecotourism guides, and others.

The Florida Master Naturalist Program is an adult education University of Florida/IFAS Extension program. Training will benefit persons interested in learning more about Florida’s environment or wishing to increase their knowledge for use in education programs as volunteers, employees, ecotourism guides, and others.

Through classroom, field trip, and practical experience, each module provides instruction on the general ecology, habitats, vegetation types, wildlife, and conservation issues of Coastal, Freshwater and Upland systems. Additional special topics focus on Conservation Science, Environmental Interpretation, Habitat Evaluation, Wildlife Monitoring and Coastal Restoration. For more information go to: http://www.masternaturalist.ifas.ufl.edu/ Okaloosa and Walton Counties will be offering Upland Systems on Thursdays from February 15- March 22. Topics discussed include Hardwood Forests, Pinelands, Scrub, Dry Prairie, Rangelands and Urban Green Spaces. The program also addresses society’s role in uplands, develops naturalist interpretation skills, and discusses environmental ethics. Check the website for a Course Offering near you :http://conference.ifas.ufl.edu/fmnp/

by Les Harrison | Jan 5, 2018

St. Marks River Preserve State Park is still being developed, but open for native habitat enthusiast and those who enjoy this environment as nature established it.

Located along the banks of the St. Marks River’s headwaters, this park offers an extensive system of trails for hiking, horseback riding, and off-road bicycling. The existing road network in the park takes visitors through upland pine forests, hardwood thickets and natural plant communities along the northern banks of the river.

The St. Marks River is not navigable within the park boundaries. It is not conducive to canoeing or kayaking unless visitors are willing to accept long portages through thick undergrowth.

Most of the trails are dry and sandy, but plan for the low water crossings which some of the trails traverse. The rainy months of summer increase the prospects of water crossings.

This preserve is home to a wide variety of native fauna including black bear, deer, turkey and much more. Wildlife tracks frequently crisscross the park’s roads and trails.

At the northern end of the park two sections have had timber removed. One plot has been replanted with wiregrass seed which should germinate this year. Both areas have been planted with long-leafed pine seedlings.

This preserve offers avian aficionados the opportunity to witness nature at its finest as birds fill the air with their calls. A wide assortment of residential and migratory birds can be viewed in their natural habitat.

There are currently no amenities available at the park and it does not have restroom facilities. Additionally, visitors must bring in water for themselves or their horse.

There are no fees presently required to enjoy this gem of a park. Located east of Tallahassee, it is 3.5 miles east of W.W. Kelly Road on Tram Rd (Leon County Highway 259) almost to the Jefferson County line.

Adequate planning should be made to pack in and pack out all needed items for the day. The nearest convenience stores are located in Wacissa a few miles west of the park on Tram Road.