by Mary Salinas | Mar 18, 2021

The weather is warmer and plans and planting for spring vegetable gardens are in full swing. Last week many vegetable gardening topics were addressed in our Gardening in the Panhandle LIVE program. Here are all the links for all the topics we discussed. A recording of last week’s webinar can be found at: https://youtu.be/oJRM3g4lM78

Home grown Squash. Gardening, vegetables. UF/IFAS Photo by Tom Wright.

Getting Started

The place to start is with UF’s ever popular and comprehensive Florida Vegetable Gardening Guide https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/VH/VH02100.pdf

Many viewers expressed interest in natural methods of raising their crops. Take a look at Organic Vegetable Gardening in Florida https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/HS/HS121500.pdf

The Square Foot Vegetable Planting Guide for Northwest Florida helps plan the layout of your garden https://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/media/sfylifasufledu/leon/docs/pdfs/Vegetable-Square-Foot-Planting-Guide-for-Northwest-Florida-mcj2020.pdf

Maybe you would like the convenience of starting with a fresh clean soil. Gardening in Raised Beds can assist you. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ep472 Also see Gardening Solutions Raised Beds: Benefits and Maintenance https://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/design/types-of-gardens/raised-beds.html

Here is a guide to Fertilizing the Garden https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/vh025

The Florida Panhandle Planting Guide will help you decide what to plant and when: https://www.facebook.com/SRCExtension/posts/4464210263604274

The Ever-Popular Tomato

To start your journey to the best tomatoes, start with UF/IFAS Gardening Solutions – Tomatoes https://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/plants/edibles/vegetables/tomatoes.html

If you are looking to grow in containers: https://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/media/sfylifasufledu/leon/docs/pdfs/Container-Gardening-Spacing-Varieties-UF-IFAS-mcj2020.pdf

Vegetable grafting is gaining in popularity, so if interested, look at this Techniques for Melon Grafting: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/hs1257

Blossom end rot occurs when irrigation is irregular and the calcium in the soil does not get carried to the developing fruit. The U-Scout program has a great description of this common problem: https://plantpath.ifas.ufl.edu/u-scout/tomato/blossom-end-rot.html

Our moderators talked about some of their favorite tomato varieties. Josh Freeman is partial to Amelia, a good slicing tomato. Matt Lollar shared some of the best tomato varieties for sauce: Plum/Roma types like BHN 685, Daytona, Mariana, Picus, Supremo and Tachi. For cherry tomatoes, Sheila Dunning recommended Sweet 100 and Juliette.

Whatever variety you choose, Josh says to pick when it starts changing color at the blossom end and bring it indoors to ripen away from pests.

Garden Pest Management

Let’s start with an underground pest. For those of you gardening in the native soil, very tiny roundworms can be a problem. Nematode Management in the Vegetable Garden can get you started: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/NG/NG00500.pdf

Leaffooted bugs are quite a nuisance going after the fruit. Here is how to control them: http://extension.msstate.edu/newsletters/bug%E2%80%99s-eye-view/2018/leaffooted-bugs-vol-4-no-24

Cutworms are another frustration. Learn about them here: https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/hort/2020/02/27/cutworms-the-moonlit-garden-vandals/

Maybe your tomatoes have gotten eaten up by hornworms. https://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/care/pests-and-diseases/pests/hornworm-caterpillars.html

There are beneficial creatures helping to control the pest insects. Learn to recognize and conserve them and make for a healthier environment. Natural Enemies and Biological Control: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/IN/IN12000.pdf

If the beneficials are not numerous enough to control your pests, maybe a natural approach to pest control can help. Natural Products for Managing Landscape and Garden Pests in Florida: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in197

Fungal and bacterial problems can also plague the garden. Go to Integrated Disease Management for Vegetable Crops in Florida for answers: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/PP/PP11100.pdf

Get control of weeds early and consult Controlling Weeds by Cultivating & Mulching https://hgic.clemson.edu/factsheet/controlling-weeds-by-cultivating-mulching/

Companion planting is a strategy that has been around for ages and for good reason: https://www.almanac.com/companion-planting-chart-vegetables Some good flowering additions to the garden that Sheila talked about are bee balm, calendula, marigold, nasturtiums, chives, and parsley.

And Some Miscellaneous Topics…

Peppers are another popular crop. Get some questions answered here: https://aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu/archives/parsons/vegetables/pepper.html

When can we plant spinach in Northeast Florida? http://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/nassauco/2017/07/15/q-can-plant-spinach-northeast-florida/

Figs are a great fruit for northwest Florida. Get started here: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/MG/MG21400.pdf and with this https://aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu/extension/homefruit/fig/fig.html

by Ray Bodrey | Feb 25, 2021

Bananas are a great choice for your landscape, whether as an edible fruit producer or simply as an ornamental, giving your space a tropical vibe.

Bananas are native to southeast Asia, however, grow well across Florida. Complementary plants that can be paired with bananas in the landscape are bird of paradise (banana relative), canna lily, cone ginger, philodendron, coontie, and palmetto palm, just to name some.

Bananas are very easy to manage during the warmer months. Bananas are water loving, and that’s putting it lightly. Planting in vicinity of an eave on your home is a good measure for site suitability. Roof rainwater will drastically increase the growth of the banana tree and decrease the need for supplemental irrigation. Banana trees will need full sun and high organic moist soils create the best environment. For nutrition, a seasonal one-pound application of 6-2-12 fertilizer is a good practice to sustain older trees. Young trees should be fertilized every two months for the first year at a rate of a half-pound.

Musa basjoo is one of the most cold hardy banana varieties. Photo Credit: University of Florida/IFAS Extension

If there is a con to banana trees, it’s their cold hardiness. Some varieties fair well and others some not so much. ‘Dwarf Cavendish’ (Musa acuminate) is a popular variety that is found in many garden centers in the state. It produces fruit very well, but it is not very cold hardy. ‘Pink Velvet’ (Musa velutina) produces fruit with a bright pink peel, but isn’t very cold hardy either. A couple of cold hardy ornamental varieties are the ‘Japanese Fiber’ (Musa basjoo) and ‘Black Thai’ (Musa balbisiana), which is by far the most cold hardy, with the ability to easily combat below freezing temperatures.

Freeze damage on a banana tree. Photo Credit: Ray Bodrey, University of Florida Extension – Gulf County

Regardless of cold hardiness, in many cases, banana trees will turn brown after freezing temperatures occur or even if the temperatures reach just above the freezing mark, but will bounce back in the spring. Until then, it’s important not to prune away the brown leaves or trunk skin. These leaves act as an insulator and help defend against freezing temperatures. Usually, the last freezing temperatures that may occur in the Panhandle are around the first of April. So, to be safe, pruning can begin by mid to late April. When pruning, be sure to be equipped with a sharp knife, gloves and work clothes. Banana trunk skin and leaves can be quite fibrous and the liquid from the tree can stain clothing and hands.

So, what’s the best variety of fruiting bananas? Most ornamental bananas do not produce tasty fruit. If you are looking for a production banana, ‘Lady Finger’, ‘Apple’, and ‘Ice Cream’ are popular varieties, but are better suited for the central and southern parts of the state.

For more information, contact your local county extension office.

Supporting information for this article can be found on the UF/IFAS Gardening Solutions website.

Also, for more information see the UF/IFAS EDIS publication, “Banana Growing in the Florida Home Landscape”, by Jonathan H. Crane and Carlos F. Balerdi.

UF/IFAS Extension is an Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Matt Lollar | Feb 18, 2021

It’s mid-February, cloudy, and cold. It’s time to get outside and take cuttings for fruit and nut tree grafting. The cuttings that are grafted onto other trees are called scions. The trees or saplings that the scions are grafted to are called rootstocks. Grafting should be done when plants start to show signs of new growth, but for best results, scion wood should be cut in February and early March.

Scion Selection

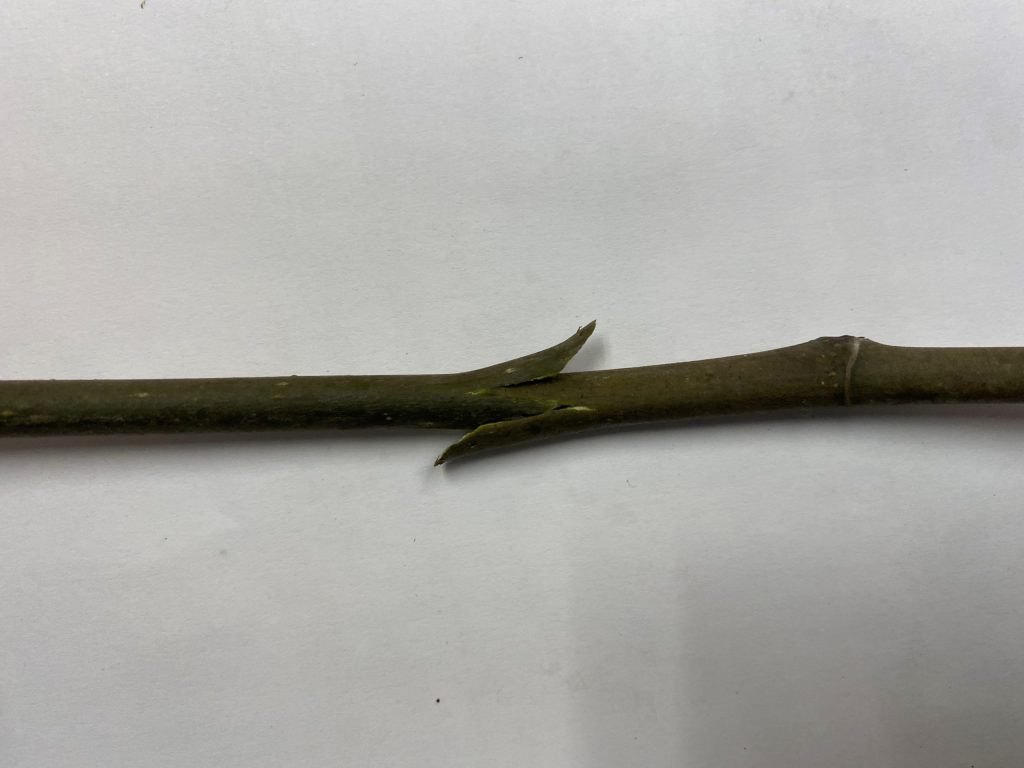

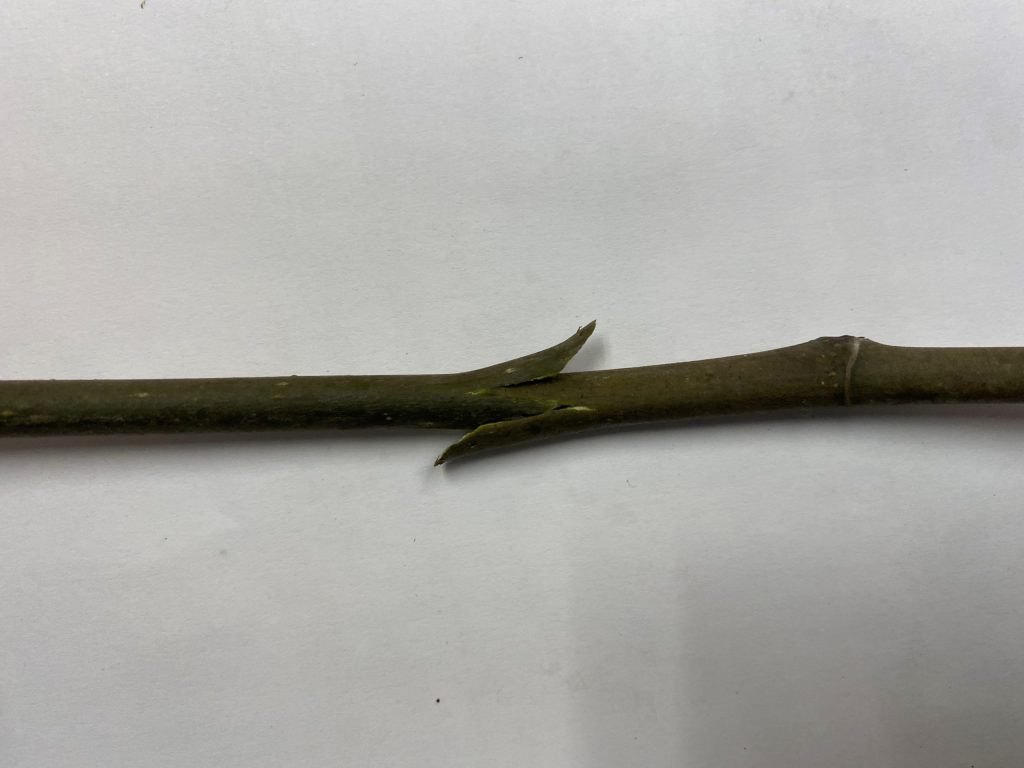

Straight and smooth wood with the diameter of a pencil should be selected for scions. Water sprouts that grow upright in the center of trees work well for scion wood. Scions should be cut to 12-18″ for storage. They should only need two to three buds each.

Scions ready for grafting. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

Scion Storage

Scions should be cut during the dormant season and refrigerated at 35-40°F until the time of grafting. If cuttings are taken in the field or far from home, then simply place them in a cooler with an ice pack until they can be refrigerated. Cuttings should be placed in a produce or zip top bag along with some damp paper towels or sphagnum moss.

Grafting

It is better to be late than early when it comes to grafting. Some years it’s still cold on Easter Sunday. Generally, mid-March to early April is a good time to graft in North Florida. Whip and tongue or bench grafting are most commonly used for fruit and nut trees. This type of graft is accomplished by cutting a diagonal cut across both the scion and the rootstock, followed by a vertical cut parallel to the grain of the wood. For more information on this type of graft please visit the Grafting Fruit Trees in the Home Orchard from the University of New Hampshire Extension.

A bench graft union. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

Achieving good bench graft unions takes skill and some practice. Some people have better success using a four-flap or banana graft technique. This type of graft is accomplished by stripping most of the bark and cambium layer from a 1.5″ section of the base of the scion and by folding the back and removing a 1.5″ section of wood from the top of the rootstock. A guide to this type of graft can be found on the Texas A&M factsheet “The Four-Flap Graft”.

Grafting is a gardening skill that can add a lot of diversity to a garden. With a little practice, patience, and knowledge any gardener can have success with grafting.

by Matt Lollar | Nov 4, 2020

From time to time we get questions from clients who are unsatisfied with the flavor of the fruit from their citrus trees. Usually the complaints are because of dry or fibrous fruit. This is usually due to irregular irrigation and/or excessive rains during fruit development. However, we sometimes get asked about fruit that is too sour. There are three common reasons why fruit may taste more sour than expected: 1) The fruit came from the rootstock portion of the tree; 2) The fruit wasn’t fully mature when picked; or 3) the tree is infected with Huanglongbing (HLB) a.k.a. citrus greening or yellow dragon disease.

Rootstock

The majority of citrus trees are grafted onto a rootstock. Grafting is the practice of conjoining a plant with desirable fruiting characteristics onto a plant with specific disease resistance, stress tolerance (such as cold tolerance), and/or growth characteristics (such as rooting depth characteristics or dwarfing characteristics). Citrus trees are usually true to seed, but the majority of trees available at nurseries and garden centers are grafted onto a completely different citrus species. Some of the commonly available rootstocks produce sweet fruit, but most produce sour or poor tasting fruit. Common citrus rootstocks include: Swingle orange; sour orange; and trifoliate orange. For a comprehensive list of citrus rootstocks, please visit the Florida Citrus Rootstock Selection Guide. A rootstock will still produce viable shoots, which can become dominant leaders on a tree. In the picture below, a sour orange rootstock is producing a portion of the fruit on the left hand side of this tangerine tree. The trunk coming from the sour orange rootstock has many more spines than the tangerine producing trunks.

A tangerine tree on a sour orange rootstock that is producing fruit on the left hand side of the tree. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension

Fruit Maturity

Florida grown citrus generally matures from the months of October through May depending on species and variety. Satsumas mature in October and taste best after nighttime temperatures drop into the 50s. Most tangerines are mature in late November and December. Oranges and grapefruit are mature December through April depending on variety. The interesting thing about citrus fruit is that they can be stored on the tree after becoming ripe. So when in doubt, harvest only a few fruit at a time to determine the maturity window for your particular tree. A table with Florida citrus ripeness dates can be found at this Florida Citrus Harvest Calendar.

Citrus Greening

Citrus Greening (HLB) is a plant disease caused by the bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus, which is vectored by the Asian citrus psyllid. The disease causes the fruit to be misshapen and discolored. The fruit from infected trees does not ripen properly and rarely sweetens up. A list of publications about citrus greening can be found at the link Citrus Greening (Huanglongbing, HLB).

A graphic of various citrus greening symptoms. Photo Credit: University of Florida/IFAS Extension

by Larry Williams | Oct 28, 2020

Nice fall crop of satsuma fruit. Photo credit: Larry Williams

When asked what kind of citrus to grow here in North Florida, my default response is satsuma. I usually get a funny look, followed by an attempt by the person who’s asking to repeat the name satsuma. The individual may ask, “What is satsuma… is that a citrus?” I guess the person expected to hear orange, grapefruit, lemon or maybe tangerine.

Satsuma is a type of citrus, technically classified as a mandarin and is sometimes referred to as satsuma mandarin. The satsuma mandarin is a good candidate for the North Florida citrus enthusiast for a number of reasons.

- Historically, mature dormant trees have survived minimum temperatures of 14°F to 18°F when budded/grafted to a cold-hardy rootstock such as trifoliate orange or swingle, a trifoliate orange cross. Young trees are not as cold-hardy but, due to their smaller size, are more easily covered with a cloth such as a sheet or lightweight blanket for protection during freezes.

- Satsuma fruit are ready to harvest October through December, ripening before the coldest winter temperatures. This is not true with most sweet citrus types such as oranges, which are harvested during winter months. Harvesting during winter works well in Central and South Florida where winters are mild but does not work well here in extreme North Florida. The potentially colder winter temperatures of North Florida are likely to result in the fruit on sweet oranges freezing on the tree before they are ripe, potentially ruining the fruit.

- Our cooler fall temperatures result in higher sugar content and sweeter fruit.

- Fruit are easily peeled by hand, have few to no seed and are sweet and juicy.

- Trees are self-fruitful, which means that only one tree is needed for fruit production. This is important where space is limited in a home landscape.

- Trees are relatively small at maturity, reaching a mature height of 15 to 20 feet with an equal spread.

- Branches are nearly thornless. This may not be true with shoots originating at or below the graft union. Shoots coming from the rootstock may have long stiff thorns. These shoots should be removed (pruned out) as they originate.

Satsuma fruit are harvested in fall but trees are best planted during springtime when temperatures are mild and as soil is warming. Availability of trees is normally better in spring, as well. For additional cold protection, purchase a satsuma grafted on trifoliate orange rootstock and plant the tree on the south or west side of a building. There are a number of cultivars from which to choose.

For more info on selecting and growing satsuma mandarin, contact the UF/IFAS Extension Office in your County or visit the following website.

https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ch116

by Sheila Dunning | Aug 31, 2020

Photo from USDA APHIS

Remember last year’s vacation trip? You picked the perfect location, checked into the hotel and made sure to check every mattress corner for bedbugs. Bugs can hide in the strangest places. Now with COVID-19 those people insisting on still taking a vacation are flocking to Northwest Florida. While some are still utilizing hotels, the majority are pulling into the RV park or campground. They are bringing anything and everything anyone could possibly need for the week, from firewood to camp chairs. That way no one will have to go to the store. Somewhere on the vehicle or within all the stuff there may be some hitchhikers, insect stowaways. The problem is that these bugs may be staying even after the human beings head back north. Florida is notorious for invasive species. With 22 international airports and 15 international ports in the state, hundreds of foreign insects are intercepted each month. But, not all the problem creepy crawlers are coming from the south. Many have been introduced to northern states and work their way here.

One to keep an eye open for is spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula). The Asian native was first detected in Pennsylvania in 2014. Since then it has spread to the east and south. While the insect can walk, jump, or fly short distances, the quickest way for the spotted lanternfly to relocate is to lay eggs on natural and man-made surfaces. Some of those egg masses may fall off and get left at the park. Next spring after the eggs hatch the nymphs will begin feeding on the sap of numerous plants, often changing species as they mature. Host plants include grape, maple, poplar, willow and many fruit tree species.

Nymphs in the early stages of development appear black with white spots and turn to bright red before becoming adults. At maturity spotted lanternflies are about 1 ½ inches wide with large colorful, spotted wings.

Photo from USDA APHIS

At rest their forewings are folded up giving the lanternfly a dull light brown appearance. But when it takes flight its beauty is revealed. The bright red hind wings and the yellow abdomen are very eye-catching. Remember, in nature bright colors are often a warning. Though spotted lanternflies are attractive, they pose a valid threat to native and food-producing plants. The adults feed by sucking sap from branches and leaves. What goes in must come out. Sugar in, sugar out. Spotted lanternflies excrete a sticky, sugar-rich fluid referred to as honeydew. Black sooty mold often develops on honeydew covered surfaces.

Spotted lanternflies are most active at night, steadily migrating up and down the trunk of trees. During the day they tend to gather together at the base of the plants under a canopy of leaves. So, you may need your lantern (or head lamp) to locate them. If you find an insect that you suspect is a spotted lanternfly, please contact your local Extension office of the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Division of Plant Industries.

Photo by USDA APHIS