by Ray Bodrey | Apr 8, 2020

Spring has arrived and so have the insects. Caterpillars are crawling around and one possesses a unique appetite.

Neodiprion spp. is the most common defoliating insect group affecting pine trees. In all, there are 35 species that are native to the U.S. and Canada. The redheaded pine sawfly, Neodiprion lecontei, is the primary species found in the Florida Panhandle.

Adult sawflies can be as large as 1/3 of an inch in length. The female can be two-thirds larger than the male and are mostly black with a reddish-brown head, with occasional white coloration on the sides of the abdomen.

Mature larvae of the redheaded pine sawfly. Credit: Patty Dunlap, Gulf County Master Gardener.

The ovipositor, the tube-like organ used for laying eggs, is saw-like, hence the common name. During the fall, females make slits in pine needles and deposit individual eggs, up to 120 eggs at a time. The eggs are shiny, translucent and white-hued. Mature larvae (caterpillars), as seen in the accompanying photo, are yellow-green, emerge in the spring and feast on pine needles. After weeks of feeding on needles, the mature larvae drop to the ground. The cocoon, a reddish-brown, thin walled cylinder, is spun in the upper layer of the soil horizon or in the leaf litter; this is called the pupae stage. The pupae overwinter, and adults emerge from the cocoon in the spring of the following year.

Mature larvae are attracted to young, open growing pine stands. Pine is the preferred host, but cedar and fir, where native, are secondary food sources. Neodiprion lecontei is an important defoliator of commercially grown pine, as the preferred feeding conditions for sawfly larvae are enhanced in monocultures of shortleaf, loblolly, and slash pine, all of which are commonly cultivated in the southern United States. Defoliation can kill or slow the growth of pine trees as well as predispose trees to other insects or disease.

Are there control methods? Yes, biological control is a major factor, as natural enemies are numerous. Disease, viruses and predators help regulate population control. For small scale control, physically removing eggs or larvae is key. Again, most infestations occur on younger tree plantings, so they’ll be in reach. Be sure to scout young pines for signs of infestation. Horticultural soaps and oils are effective chemical controls, if needed.

For more information, contact your local county extension office.

Supporting information for this article can be found in the UF/IFAS Extension EDIS publication, “Redheaded Pine Sawfly Neodiprion lecontei” by Sara DeBerry: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/IN/IN88200.pdf

UF/IFAS Extension is an Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Sheila Dunning | Mar 20, 2020

Until recently, rainfall has been plentiful. That’s great for the water table and preparing plants to wake up for spring. But, insects are also stirring. Bugs are affected by rain in many ways. When water is plentiful, they can grow faster, reproduce sooner and travel farther. Combine that with the fact that the insects’ homes are being flooded out and their normal food sources are displaced; and where do you think they are headed? Yes, into your house. Four bugs you can anticipate seeing after rain events include cockroaches, sowbugs, ants and centipedes.

American Cockroach

Photo by: J.L. Castner

UF/IFAS

Roaches tend to live in places that flood easily, especially this time of year. To survive the cold nights, cockroaches need to find a warm place to rest. Typically those places would be drains, pipes, sewers, along foundations and in crawl spaces. But, when it rains, these locations are often flooded, forcing cockroaches to scurry for their lives to avoid drowning. A crack in weather stripping or window caulking makes a quick hideaway. Once inside, they may decide to stay. Frequent rainy days create the lingering humidity that makes all kinds of places more livable for roaches.

Sowbugs and his cousin, the pillbug, are very small, pill-shaped pests with multiple legs and a series of shell-like plates. Often referred to as roly-polys, these creatures are actually a form of land

Sowbug

Photo by: J.L. Castner UF/IFAS

crustacean related to lobsters, crabs, and crayfish. The sowbug’s breathing tubes require moisture to function properly, so they must stay near water. Typically this fact restricts the sowbug to living in moist soil or sand. Ending up inside a building is normally a terminal condition for them. However, due to the moisture left in the air after a rain event, sowbugs that seek refuge inside are able to survive for longer periods of time. Given the opportunity, sowbugs will reproduce indoors. If they have decaying organic material to feed on, they may stick around even longer; having time to create a multi-generational infestation.

Carpenter Ant

Photo by: J.L.Castner

UF/IFAS

Ants are never too far away. They usually build their colonies in the soil near convenient sources of food and shelter. Being in the ground puts ant colonies at great risk for flooding out, even with short periods of rainfall. When this happens, ants are forces to find higher, drier ground quickly or risk being washed away. What better place than a house? Once inside, the ants get back to work looking for food and building the colony. Expect to see ants around kitchen sinks, on window sills and working their way into cupboards and pantry areas during and after a heavy rain. Unfortunately, if they find all the elements needed to make their home, the ants will be very reluctant to go back outside.

Centipede Photo by: J.L. Castner UF/IFAS

Like the other pests mentioned, centipedes are attracted to humid environments. But, centipedes are active hunting carnivores. They like to feed on roaches, sowbugs and ants. So, they follow them into the house, a well-stocked hunting ground. Centipedes typically only hunt late at night, but in dark areas they can hunt day and night. Finding centipedes if most likely an indication of another pest infestation.

These rain-displaced pests may need some help from a pest control product and/or operator to be discouraged from staying inside. We need the rain. But, keep a close watch for the unwanted visitors.

by Larry Williams | Mar 20, 2020

Ground-dwelling bees get a lot of attention in late winter and spring as they create large numbers of small mounds in local lawns and landscapes.

Many people become concerned as they see these bees hovering close to the ground out in their lawns and landscapes. But these bees are interesting, docile, beneficial and are unlikely to sting.

These bees are known as andrenid bees or mining bees. Andrenid bees are solitary. As the name implies, they live alone. However, they may nest in close proximity to one another but they do not form a colony or hive. They produce individual mounds with a small entrance hole. The bees are approximately ½ inch in length with a black body.

Richard Sprenkel, retired UF/IFAS Entomologist, explains their biology in today’s article.

Richard Sprenkel, retired UF/IFAS Entomologist, explains their biology in today’s article.

“After mating in late winter and early spring, the female selects a site that has dry, loose soil with sparse vegetation. She excavates a vertical shaft in the soil that is approximately the diameter of a pencil and up to eighteen inches deep. Off of the main shaft, the female will construct several brood chambers that she lines with a waterproof material. The female bee provisions each brood chamber with pollen and nectar on which she lays an egg. The pollen and nectar sustain the larva until fall when the overwintering adult is formed. Early the following spring, adult bees emerge from the ground to begin the cycle again. There is one generation per year.”

The small mound of soil that is excavated from each burrow brings additional attention to the activity of the bees. As males continue to hover in the area of the burrows looking for unmated females, the bees appear more menacing than they actually are. Andrenid bees have a tendency to concentrate their nests in a relatively small area. The openings to the underground burrows may be no more than three to four inches apart.

The threat of being stung by these bees is usually highly overrated. The males cannot sting and the females are docile and not likely to sting unless stepped on, handled or threatened. While entrances to the tunnels and excavated soil may appear disruptive to the lawn, they usually are not damaging. It may appear that the grass is thin because of the bees but it is more likely that the bees are in the area because the grass was already thin. Control is usually not necessary. Because the andrenid bees forage to gather pollen and nectar, they are actually beneficial. They serve as pollinators this time of the year.

**** Photo Credited to UF / IFAS Extension Jackson County courtesy of Josh Thompson****

by Molly Jameson | Feb 27, 2020

Larva of the granulate cutworm (Feltia subterranea). Photo by John L. Capinera, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida.

One of the biggest predicaments growing vegetables in my backyard garden is dealing with cutworms. Cutworms are a type of nocturnal moth larvae that feed by wrapping themselves around seedling stems at the soil surface. They then cut the stem of the seedling in two – as if Edward Scissorhands dropped by for a visit – killing the plant. There are multiple species, but one of the most common in Florida is the granulate cutworm (Feltia subterranea). They are distributed most frequently in the tropics but can occur as far north as Southern Canada and regularly occur in the Southeastern United States.

My plan was to install cutworm collars the next morning. But that night, cutworms chewed through the stem of this tomato seedling in two locations. Photo by Molly Jameson.

Since cutworms feed at nighttime it is particularly frustrating, as you will find plants which appeared fine in the evening destroyed by morning. What’s even more frustrating is they feed in multiple seasons on a very wide range of crops, including tomatoes, beans, corn, eggplant, lettuce, peppers, watermelon, celery, broccoli, cabbage, and kale, to name a few. This fall and winter, I even found they had attacked my carrots and onions, which I thought would be more resistant.

One approach a backyard gardener can take in combatting cutworms is to use physical barriers. Netting or row cover can help prevent mature moths from ovipositing their eggs. But if you already have larvae invading, this technique will be ineffective.

For plants with stems less than pencil-width thick, make cutworm collars to help protect young seedlings from attack. Photo by Molly Jameson.

Plants with stems that are less than pencil-width thick are most susceptible to cutworm damage. A useful tactic is to make what are called “cutworm collars.” Surround individual seedlings with toilet paper rolls, taking care not to break fragile stems as you position the rolls over the plants. Materials such as soda cans or cereal boxes can be cut into strips to encircle seedlings if toilet paper rolls are too small to safely fit over the plant. Try to extend the cardboard two inches below and two inches above the soil surface. In this way, the cardboard acts as a barrier, and can help keep cutworms from accessing the stems.

Unfortunately, if cutworms are already hiding in soil close to the plants, the collars might not be effective. Another technique to try, especially if cutworms are already present, is the toothpick method. Place two toothpicks vertically in the soil on each side of the stem. They should be right up against the stem. In this manner, the toothpicks should prevent the cutworm from wrapping around the stem to chew through.

This onion start was given a moonlit haircut by feasting cutworms. If you are lucky, you may be able to find the culprit by digging around the soil adjacent to the afflicted plant. Photo by Molly Jameson.

It can also be helpful to scout your garden for cutworms. Carefully dig one to two inches into the soil near afflicted seedlings. The caterpillars are small, growing from a few millimeters up to less than two inches in length, but tend to stay curled up near the soil surface within about a foot radius of their vegetative victims. Crush any cutworms you find, or for the squeamish, simply drop the cutworms into soapy water.

Applying the bacterial insecticide Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki (Bt for short) may help control cutworms but be sure to apply in the evenings and not before a rainfall or irrigation event, as sunlight and water render Bt useless. And keep in mind, cutworms must digest Bt to be effective, so you may need to apply multiple applications. As with any insecticide, always remember to follow the directions on the label. Once seedling stems grow larger than pencil-width, they should be safe from cutworm mayhem. That is… until the next garden vandal comes along!

To learn more, visit the University of Florida Entomology and Nematology Department’s Featured Creatures page about the granulate cutworm (http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/veg/granulate_cutworm.htm). You can also search for cutworms on the UF/IFAS EDIS website to learn about additional cutworm species found in our area (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/).

by Beth Bolles | Feb 27, 2020

Landscape activities have already begun in our Panhandle counties with cleanup, mulching, raking, and pruning. Our mild temperatures and days with sunshine spur us to jump into our landscape preparations for the spring growing season.

This year before you send all your debris to the compost pile or patch up thinning turf areas, consider that some landscape imperfections may actually be good for local wildlife.

We all know how important it is to plant nectar attracting plants for bees but there are other easy practices that can help promote more native bees in local landscapes. There are some solitary native bee pollinators that will raise young in hollow stems of plants. Instead of cutting all your old perennial or small fruit stems back to the ground, let some stay as a home to a native pollinating bee. This does not have to detract from the look of the landscape but can be on plants in the background of a border garden or even hidden within the regrowth of a multi stemmed plants. Plants that are especially attractive to native bees have a pithy or hollow stems such as blackberry, elderberry, and winged sumac.

The hollow stems of upright blackberries can be home to solitary bees. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF IFAS Extension Escambia County

Another favorite site for solitary bees is in the ground. These ground nesting solitary bees should not be compared to yellow jacket wasps. Solitary bees are not aggressive. Mining or digger bees need some bare soil surfaces in order to excavate small tunnels for raising a few young. Maybe you have an area that does not need a complete cover of turf but is fine with a mixture of turf and ‘wildflowers’. A few open spaces, especially in late winter and early spring will be very attractive to solitary bees.

Beneficial solitary bee mounds in the ground of a winter centipedegrass lawn area. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF IFAS Extension Escambia County

One of our fastest disappearing homes for wildlife are natural cavities. In residential sites, we often prune or remove limbs or trees that are declining or have died. If the plant or tree is not a hazard, why not leave it to be a home for cavity nesting birds and mammals. If the dying tree is large, have a professional remove hazard pieces but leave a trunk about 10-15 feet tall for the animals to make a home. You may then get to enjoy the sites and/or sounds of woodpeckers, bluebirds, owls, flying squirrels, and chickadees.

by Carrie Stevenson | Feb 18, 2020

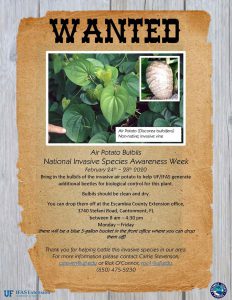

Several Extension offices in the Panhandle are collecting air potato bulbils for National Invasive Species Week. Photo credit: Esther Mudge, Escambia County

The non-native invasive air potato vine (Discorea bulbifera) has wound its way throughout Florida, from pine forests and creek floodplains to backyards. Their heart-shaped leaves are most noticeable in the spring and fall, where they can take over large areas, not unlike their fellow invasive vine, kudzu. In the fall, the plant produces a potato-like tuber called a bulbil, which grows above ground on the vine. The bulbils drop in the winter and then produce new vines the following spring.

The vine’s growth has been uncontrolled or kept back by herbicide for years, until researchers discovered a biological control insect known as the air potato leaf beetle (Liloceris cheni). In the vine’s native Nepal and China, the beetle controls growth by surviving on the leaves of the air potato, its sole food source. After extensive study, the USDA approved the use of these beetles in Florida to control the air potato vine population here. UF IFAS Extension offices statewide have participated in these beetle release programs, providing thousands of beetles to homeowners and property owners seeking to manage the invasive vine using a chemical-free technique. Left alone, air potato vines can smother full-sized trees, blocking the sunlight and causing them to collapse under the weight of the intertwined vines.

From 2012-2015, beetles were able to reduce air potato vine coverage and bulbil density by 25-70% (depending on location and density of beetle population). The active beetle-production phase of a UF IFAS grant has ended, but researchers are committed to the goal of reducing this nuisance species statewide.

To assist with this process, several Extension offices in the Panhandle are sponsoring a bulbil collection during National Invasive Species Week (NISAW, February 23-29). This effort will serve two important roles: to remove bulbils from the natural environment and to provide a seed source for university researchers seeking to grow air potato vine in a controlled environment, sustaining a continued population of air potato beetles for distribution.

For more information on Air Potato Vines and Leaf Beetles, visit https://bcrcl.ifas.ufl.edu/airpotatobiologicalcontrol.shtml or contact your local County Extension office.

Richard Sprenkel, retired UF/IFAS Entomologist, explains their biology in today’s article.

Richard Sprenkel, retired UF/IFAS Entomologist, explains their biology in today’s article.