by Larry Williams | Sep 2, 2016

Tropical sod webworms have been active in local lawns during the past few weeks here in North Florida. All of our warm season turf grasses are susceptible to these pests.

Sod webworms are not consistently a problem every year. Some years their numbers are low enough that they are not a problem. Some years we do not see them at all. Those years when they are a problem, it’s usually not until late summer and early fall that they become active and they may continue to feed on lawns until frost occurs.

Fall armyworm. Photo credit: Frank Peairs Colorado State University, bugwood.org.

Fall armyworms and sod webworms can attack at the same time. Sod webworms are the smaller of the two species, reaching a length of about ¾ inch. Armyworms grow to ½ inch in length. Both of these caterpillars are greenish when young, turning brown at maturity. Armyworms generally have a light mid-stripe along their back with darker bands on either side of the mid-stripe. Their feeding is similar, resulting in notched or ragged leaf edges.

Sod webworms tend to feed in patches while armyworms cause more scattered damage. Sod webworms feed at night while armyworms will be seen feeding during the day. Sod webworm caterpillars rest, curled up near the soil surface during the day. Adults of both species are fairly small grayish to brown moths.

If your lawn has damaged spots, look closely for notched leaf blades from their chewing. You may first notice a patch in your lawn that looks like it has been mowed extra low. Closer inspection reveals grass blades that are chewed away. Caterpillar feeding on zoysiagrass shows up more as translucent whitish tan areas on the surface of individual blades more so than as notched blades.

Fall armyworms and sod webworms can be controlled with the same insecticides as the other lawn insects. But you also may use insecticides that contain Bacillus thuringiensis; a bacterium that only kills caterpillars. Control should only be directed against the caterpillars, not the non-feeding, flying adult moths. Always follow the label directions and precautions for any pesticide you use.

For more information on lawn caterpillars contact the UF/IFAS Extension Office in your County or visit http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/topic_tropical_sod_webworm.

by Les Harrison | Aug 23, 2016

Air potato leaf beetle. Photo credit: Les Harrison, UF/IFAS.

A small, but brightly colored beetle has appeared in north Florida: the air potato leaf beetle (Liliocetis cheni), a native of East Asia. The beetle, less than half an inch long, has a candy apple red body that stands out against green leaves and the more muted earth tones of most other bugs. The striking bright glossy red coating would be the envy of any sports car owner or fire truck driver.

Unlike other arrivals to the U.S., this insect was deliberately released in 2012 for biological control of air potato. After years of testing, approval was finally given to release air potato leaf beetles to begin their foraging campaign against this invasive plant species. The beetle has very specific dietary requirements and only can complete its life cycle on air potato. The larvae and adults of this species consume the leaf tissue and occasionally feed on the tubers.

When a population of air potato leaf beetles finish off an air potato thicket, they go in search of nourishment from the next patch of air potato. They are sometimes seen during stopovers while in search of their next meal.

Air potato (Dioscorea bulbifera) is an herbaceous perennial vine which is easily capable of exceeding 60 feet in length. It quickly will climb over any plant, tree or structure unfortunate enough to be in its vicinity. The vine also produces copious quantities of potato-like tubers suspended from its vines. Unless collected and destroyed, most of the easily camouflaged potatoes will germinate and intensify the infestation.

Air potato. UF/IFAS Photo: Thomas Wright.

Air potato came to Florida in 1905 from China and quickly escaped into the wild. By the 1980’s it was a serious pest species in south and central Florida, but has gradually become established in the panhandle, too. Chemical control of the air potato has been difficult. Repeated herbicide treatments are required to kill a thicket with multiple plants.

Unlike the air potato leaf beetle that only eats air potato, kudzu bugs eat their namesake vine (kudzu), but also feed on a number of other plants including a wide selection of valuable legumes and be quite destructive. Kudzu bugs were accidently introduced in north Georgia in 2009 and have spread across the south in the ensuing years and become established in north Florida.

It is a pleasant surprise to know air potato leaf beetles are working to limit the invasive air potato vine, but it is sad to think there is plenty more for them to eat.

To learn more about the air potato and the beetle:

Natural Area Weeds: Air Potato (Dioscorea bulbifera)

Air Potato Leaf Beetle Publication

by Ray Bodrey | Aug 19, 2016

Being a gardener in the panhandle has its advantages. We’re able to grow a tremendous variety of vegetables on a year-round basis. However, in this climate, plant diseases, insects and weeds can often thrive. Usually, chemical measures are applied to thwart these pests. Some panhandle gardeners are now searching for techniques regarding a more natural form of gardening, known as organic. With fall garden planting just ahead, this may be an option for conventional vegetable gardeners looking for a challenge.

Vegetable Garden at UF/IFAS Extension Wakulla County. Photo credit: Ray Bodrey UF/IFAS.

So, what is organic gardening? Well, that really depends on who you ask. A broad definition is gardening without the use of synthesized fertilizers and industrial pesticides. Fair warning, “organic” does not translate into easier physical gardening methods. Laborious weeding and amending of soil are big parts of this gardening philosophy. This begs the question, why give up these proven industrial nutrient and pest control practices? Answer: organic gardening enthusiasts are extremely health conscious with the belief that vigorous outdoor activity coupled with food free of industrial chemicals will lead to better nutrition and health.

As stated earlier, the main difference between conventional and organic gardening is the methods used in fertilization and pest control. In either gardening style, be sure to select a garden plot with well-drained soil, as this is key for any vegetable crop. Soil preparation is the most important step in the process. To have a successful organic operation, the garden will require abundant quantities of organic material, usually in the form of animal manures and compost or mixed organic fertilizer. These materials will ensure water and nutrient holding capacity. Organic matter also supports microbiological activity in the soil. This contributes additional nutrients for plant uptake. Organic fertilizers and conditioners work very slowly. The vegetable garden soil will need to be mixed and prepped at least three weeks ahead of planting.

Effective organic pest management begins with observing the correct planting times, selection of the proper plant variety and water scheduling. Selecting vegetable varieties with pest resistant characteristics should be considered. Crop rotation is also a must. Members of the same crop family should not be planted repeatedly in the same organic garden soil. Over watering can be an issue. Avoid soils from becoming too wet and water only during daylight hours.

For weed management, using hand tools to physically removing weeds is the only control method. As for insect management, planting native plants in the immediate landscape of the organic garden will help draw in beneficial insects that will feast on garden insect pests. The use of horticultural oil or neem oil is useful. However, please read the product label. Some brands of oils are not necessarily “organic”. Nematodes, which are microscopic worms that attack plant roots, are less likely an issue in organic gardens. High levels of organic matter in soil causes an inhospitable environment for nematodes. Organic disease management unfortunately offers little to no controls. Sanitation, planting resistant varieties and crop rotation are the only defense mechanisms. Sanitation refers to avoiding the introduction of potential diseased transplants. Disinfecting gardens tools will also help. Hydrogen peroxide, chlorine and household bleach are disinfecting chemicals allowed in organic gardening settings as these chemicals are used in organic production systems for sanitation. Staking and mulching are also ways to keep plants from diseases by avoiding contact with each other and the soil.

Organic gardening can be a challenge to manage, but better health and nutrition could be the reward. Please take the article recommendations into consideration when deciding on whether to plant an organic garden. For more information, contact your local county extension office.

Supporting information for this article can be found in the UF/IFAS EDIS publication, Organic Vegetable Gardening in Florida, by Danielle D. Treadwell, Sydney Park Brown, James Stephens, and Susan Webb.

by Sheila Dunning | Aug 19, 2016

With all the media discussion of “bad” insects, like mosquitoes, many of the good guys are forgotten. One that has been very active this summer is the blue mud dauber, Chalybion californicum. These wasps are metallic blue, blue-green or blackish in color with very short narrow waists. During the summer, female blue mud daubers build nests by bringing water to abandoned mud nests made by other species of mud dauber wasps. They form new mud chambers, stock them with paralyzed spiders and a single egg, then seal the chambers with more mud. Their offspring stay in the chamber, feeding on the spiders, and then pupate in a thin silk cocoon. They spend the winter in the nest, emerging the following spring as adults.

With all the media discussion of “bad” insects, like mosquitoes, many of the good guys are forgotten. One that has been very active this summer is the blue mud dauber, Chalybion californicum. These wasps are metallic blue, blue-green or blackish in color with very short narrow waists. During the summer, female blue mud daubers build nests by bringing water to abandoned mud nests made by other species of mud dauber wasps. They form new mud chambers, stock them with paralyzed spiders and a single egg, then seal the chambers with more mud. Their offspring stay in the chamber, feeding on the spiders, and then pupate in a thin silk cocoon. They spend the winter in the nest, emerging the following spring as adults.

Blue mud daubers are solitary wasps and not known to be aggressive. When the females have carried water to an old black and yellow mud dauber’s nest, she softens it and remolds it to her needs. The result is a very lumpy version of the originally smooth nest. Next she must fill the nest with food for her future offspring. The blue mud dauber prays on spiders.

If orb weavers, lynx or crab spiders are plentiful, the blue mud dauber is able to land on their web without getting entangled and pluck the web to simulate an insect in distress. When the spider rushes to capture its prey, the poor arachnid becomes the victim of the wasp’s paralyzing sting and is quickly flown to the mud nest. However, the preferred host of the blue mud dauber is the southern black widow. Even without the elaborate web game, this wasp can control a dangerous nuisance. Once at the nest with her spider victim, the blue mud dauber stores the paralyzed arachnid at the bottom of a mud cell and lays a single egg onto its body. When the wasp larva hatches it consumes the remaining body of the spider. With a full belly, the mature larva spins a papery silken cocoon within the mud nest and begins to pupate. The following spring an adult wasp chews a round hole in the end of the mud cell and exits it’s winter home.

If orb weavers, lynx or crab spiders are plentiful, the blue mud dauber is able to land on their web without getting entangled and pluck the web to simulate an insect in distress. When the spider rushes to capture its prey, the poor arachnid becomes the victim of the wasp’s paralyzing sting and is quickly flown to the mud nest. However, the preferred host of the blue mud dauber is the southern black widow. Even without the elaborate web game, this wasp can control a dangerous nuisance. Once at the nest with her spider victim, the blue mud dauber stores the paralyzed arachnid at the bottom of a mud cell and lays a single egg onto its body. When the wasp larva hatches it consumes the remaining body of the spider. With a full belly, the mature larva spins a papery silken cocoon within the mud nest and begins to pupate. The following spring an adult wasp chews a round hole in the end of the mud cell and exits it’s winter home.

As adults, the blue mud dauber feeds on nectar from flowers and honeydew secreted by insects. Should you encounter a large congregation of this normally solitary wasp, don’t be alarmed. It is probably just a bunch of male blue mud daubers gathering together to sleep it off, after a heavy day of “drinking.”

So, rather than having to cover yourself in DEET just to spend the evening on the patio, brave the heat (with water bottle in hand, of course) and spend the daytime hours watching the blue mud daubers prepare their nest for next year’s young. Maybe the media will pick up on wasp that are reducing black widow populations, rather than the dangers of mosquitoes.

by Molly Jameson | Aug 12, 2016

Ants can be treated with spinosad in vegetable gardens. Photo by Molly Jameson.

There’s nothing worse than sinking your fingers into your garden soil to dig up a potato, plant a seedling, or pull up a radish, and be met with a sharp, painful sting, and little red critters rocketing up your arms. If you are a gardener in the panhandle, my bet is that you know exactly to what I refer: fire ants!

Fire ants are certainly not native to our area. These guys are an invasive species from South America that are very resilient, and many are territorial, with the potential to drive out any native ant populations. Fire ants arrived in the 1930s, and can now be found throughout most of the southeastern United States.

So when you end up with fire ant mounds engulfing your carrot patch, what can be done? Since fire ants in your garden mean fire ants in your food, the least toxic control methods are of high importance and conventional broadcast bait treatments and mound treatments should be avoided. Even in your lawn, be careful when using strong insecticidal bait treatments, as these can harm the native ant populations that help control the spread of fire ants. This can then lead to a strong resurgence of fire ant populations that can outcompete the native ants.

Although completely controlling fire ants in an area is not possible, there are sustainable management techniques that can help. Some fire ant colonies have a single queen while others have multiple queens. Either way, in order to eliminate a fire ant colony, all queens in the colony must be killed. Fire ants are omnivorous, in that they eat plants, insects, sugars, and oils. The catch is that they are only able to ingest liquids, so solid food must be brought into the colony, where larvae regurgitate digestive enzymes onto the food, breaking it down into liquids. Therefore, any method of control by ingestion will need to be in liquid form, or the ants must be able to bring the material into the colony, without first being exterminated.

Fire ants can become a problem around and in raised vegetable gardens. Photo by Molly Jameson.

There are some commercially available products that contain boric acid or diatomaceous earth. These products may reduce populations, but eliminating whole colonies with these products can be a challenge.

The use of a nervous system toxin called spinosad is effective on fire ant populations and is considered safe to use in vegetable gardens. This toxin comes from a bacterial fermentation process, and is therefore considered organic. But be aware, even though there are organic products with ingredients derived from botanical sources such as rotenone and nicotine sulfate, they should not be used in vegetable gardens. When using chemical methods of control, always follow the directions on the label carefully.

One physical method of control is the use of hot water. Three gallons of scalding water, which is between 190 to 212ºF, has been used on colonies with a success rate of 20 to 60 percent, when applied in several treatments. You will want to slowly pour the water on the colony, being extra careful not to get burned, and avoid injuring any surrounding plants. If you are like I am, and you often leave your garden hose in the hot sun, you can spray the ant colonies with the hot water, as you wait for the water to cool off enough to water the garden. Hot water control takes persistence, but you can eventually drive the ants out.

Another method of physical control is excavation. This requires digging up the mound, putting it in a bucket, and taking it to another location. Apply talcum or baby powder to your shovel handle and bucket to help prevent the ants from escaping and crawling up to sting you.

One reason fire ants are so rampant in the United States is that they have little competition or natural enemies. Scientists have released multiple species of phorid flies, natural parasites of fire ants in South America, and a few species have become established. Scientists at UF/IFAS are currently researching additional fire ant biological control methods, such as the use of a fungi, which has shown promise.

Remember, not all ants in the garden are bad guys! Many species act as roto-tillers, aerating and redistributing nutrients in the soil. They also play a role as decomposers as they assist in turning dead insects into soil nutrients. Ants can disturb garden pests by attacking them or interrupting their feeding, mating, and egg laying processes. Additionally, ants are a food source for wildlife, such as other insects, frogs, lizards, birds, spiders, and even some mammals.

by Daniel J. Leonard | Jul 26, 2016

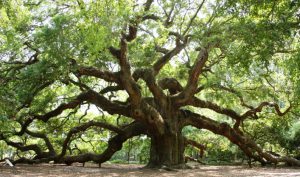

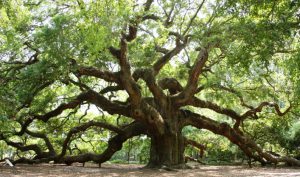

The Live Oak (Quercus virginiana) is one of the most iconic figures of the Deep South. Mentioning the words Live Oak invokes all sorts of romantic nostalgia of yesteryear and the reputation is not unearned. In fact, many Live Oaks still stand that were growing on American soil when the first English settlers set foot on Plymouth Rock. They are long-lived, picturesque trees that also happen to be nearly bulletproof in the landscape. Given these factors, it is not surprising that Live Oak is far and away the most common tree included in both residential and commercial landscapes in the Coastal South. However, even the venerable Live Oak is not without its problems; this article will discuss a few of the more common issues seen with this grand species.

The Angel Oak near Charleston, SC

Few conditions afflict live oak but when they do, improper planting or cultural practices are usually at play. Observing the following best management practices will go a long way toward ensuring the long-term health of a planted Live Oak:

- Remember to always plant trees a little higher than the surrounding soil to prevent water standing around the trunk or soil piling up around it, both of these issues frequently cause rot to occur at the base of the tree.

- If planting a containerized tree, remember to score the rootball to prevent circling roots that will eventually girdle the tree. If planting a B&B (Balled and Burlap) specimen, remember to remove the strapping material from the top of the wire basket, failure to do this can also result in the tree being girdled.

Live Oak has few insect pests but there are some that prove bothersome to homeowners. The following are two of the most common pests of Live Oaks and how to manage them:

Typical galling on Live Oak

Galls are cancerous looking growths that appear on the leaves and twigs of Live Oak from time to time and are caused by gall wasps that visit the tree and lay their eggs inside the leaf or stem of the plant. The larvae hatch and emerge from the galls the following spring to continue the cycle. These galls are rarely more than aesthetically displeasing, however it is good practice to remove and destroy gall infected stems/leaves from younger trees as gall formation may cause some branch dieback or defoliation. Chemical control is rarely needed or practical (due to the very specific time the wasps are outside the tree and active) in a home landscape situation.

- Black Twig Borers can also be problematic. These little insects seldom kill a tree but their damage (reduction of growth and aesthetic harm) can be substantial. Infestations begin in the spring in Northwest Florida, with the female twig borer drilling a pen-head sized hole in a large twig or small branch and then laying her eggs in the ensuing cavity. She then transmits an ambrosia fungus that grows in the egg-cavity, providing food for the borer, other borer adults, and her offspring that take up residence and over-winter in the twig. The activity of the insects in the twig has an effect similar to girdling; the infected twig will rapidly brown and die, making removal and destruction of the infected branches a key component

In conclusion, though there are a few problems that can potentially arise with Live Oak, its premier status and continued widespread use in the landscape is warranted and encouraged. It should be remembered that, relative to most other candidates for shade trees in the landscape, Live Oak is extremely durable, long-lived, and one of most pest and disease free trees available. Happy growing!