by Julie McConnell | Oct 23, 2017

Cypress twig galls on bald cypress leaves. Photo: J_McConnell, UF/IFAS

Bald cypress Taxodium distichum is a native tree that is commonly planted in landscapes because it is adaptable to many sites and grows quickly. It is an interesting tree because it has soft flat leaves that fall off in the winter like other deciduous shade trees; however, it belongs to the Cypress family which consists mostly of needled evergreens.

Like the other cypresses, bald cypress produces cones in the fall, which is a primary means of reproduction for the species in natural settings. During the same season that cones are maturing, you might also see what looks like cones forming at the tips of branches among the leaflets rather than along the stem. These mysterious growths are not cones but rather twig galls.

Bald cypress twig galls are abnormal growths of leaf bud tissue triggered by the attack of the cypress twig gall midge Taxodiomyia cupressiananassa. In late spring, adult midges lay eggs on new leaves of the bald cypress. As the eggs hatch and midge larvae start feeding on the bald cypress leaves the growth of a twig gall is induced. The larvae take advantage of this gall using it for food and shelter throughout the larval stage and into the pupal stage. After pupation, adults emerge from the galls, mate, and females lay an average of 120 eggs over a two-day lifespan as an adult. This first generation lays eggs on mature leaves which starts the cycle again. The galls formed by the second generation of the year fall off and overwinter on the ground.

The galls do not appear to affect the health of trees overall, although the weight of heavily infested branches may cause drooping. There are many natural enemies of the twig cypress gall midge, so applying insecticides are not recommended since they may cause harm to non-target insects. The simplest management option is to collect and destroy the galls in the spring and fall to reduce populations the following season.

To read more about bald cypress trees or the twig gall please see the following publications:

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 2, 2017

Silkgrass Pityopsis spp. Picture by: Sheila Dunning

Each fall, nature puts on a brilliant show of color throughout the United States. As the temperatures drop, autumn encourages the “leaf peepers” to hit the road in search of the red-, yellow- and orange-colored leaves of the northern deciduous trees.

Here in the Florida Panhandle, fall color means wildflowers. As one drives the roads it’s nearly impossible to not see the bright yellows in the ditches and along the wood’s edge. Golden Asters (Chrysopsis spp.), Tickseeds (Coreopsis spp.), Silkgrasses (Pityopsis spp.), Sunflowers (Helianthus spp.) and Goldenrods (Solidago spp.) are displaying their petals of gold at every turn. These wildflowers are all members of the Aster family, one of the largest plant families in the world. For most, envisioning an Aster means a flower that looks like a daisy. While many are daisy-like in structure, others lack the petals and appear more like cascading sprays.

So if you are one of the many “hitting the road in search of fall color”, head to open areas. For wildflowers, that means rural locations with limited homes and businesses. Forested areas and non-grazed pastures typically have showy displays, especially when a spring burn was performed earlier in the year.

With the drought we experienced, moist, low-lying areas will naturally be the best areas to view the many golden wildflowers. Visit the Florida Wildflower Foundation website, www.flawildflowers.org/bloom.php, to see both what’s in bloom and the locations of the state’s prime viewing areas.

And if you are want to add native wildflowers and other Florida-friendly plants to your landscape join the Master Gardeners for their Fall Plant Sale to be held Saturday, October 14 from 8 am to noon at the Okaloosa County Extension Annex located at 127 SW Hollywood Blvd, Ft. Walton Beach.

by Carrie Stevenson | Aug 11, 2017

The passionflower vine is beautiful and attracts butterflies, but can also be used for food and sedation drugs. Photo credit: Dorothy Birch

Ethnobotany lies at the intersection of culture, medicine, and mythology. The “witch doctors” and voodoo practitioners, the followers of the Afro-Cuban religion of Santeria, and the wise elders of ancient Chinese civilizations are all ethnobotanists. So, too, are the modern day field biologists who discover and develop medicinal plants into an estimated half of our pharmaceutical drugs. Simply put, ethnobotany is the study of how people and cultures (ethno) interact with plants (botany).

For tens of thousands of years, humans have been learning about plants’ chemical, nutritious, and even poisonous properties. Plants evolve these properties to defend themselves against pathogens, fungi, animals and other plants. Other properties, like color, scent, or sugar content may attract beneficial species. Humans most likely started paying attention to plant characteristics to decide whether to eat them. From there, one can imagine people started using plants to build structures or use fiber for ropes, baskets, and clothing.

My first experience with the idea of ethnobotany was as a college student on a study tour of Belize. A professional ethnobotanist took us on a tour of the Maya Rainforest Medicine Trail, pointing out dozens of native trees, shrubs, and grasses used for medicinal and cultural purposes by local tribes. From birth control and pain relief to chewing gum and pesticides, the forest provided nearly everything Central American civilizations needed to survive for thousands of years and into the present. The tour captured my imagination as I considered the possibilities yet undiscovered in the deep rainforests worldwide.

Of course, there is no need to travel out of the country, or even the state, to learn about useful native plants. One of my favorite publications put out by UF IFAS Extension specialists is “50 Common Native Plants Important in Florida’s Ethnobotanical History.” Another fascinating source of information about historic, cultural, and even murderous uses of plants is Amy Stewart’s Wicked Plants: The Weed That Killed Lincoln’s Mother and Other Botanical Atrocities. Plants with interesting historical uses make for great stories along a trail, and help create a connection between the casual observer and the natural world around them.

A handful of interesting native plants with significant medicinal properties include the cancer-fighting plants saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) and mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum). Saw palmetto berries are used for prostate cancer treatment, while the $350+ million annual Florida mayapple harvest helps produce chemotherapy drugs for several types of cancer. The carnivorous bog plant, pink sundew (Drosera capaillaris) uses enzymes to break down insect protein, and Native American tribes used the plant for bacterial and fungal skin disorders.

Sundews, tiny carnivorous plants found in pitcher plant bogs, use an enzyme to dissolve insect proteins. Native Americans recognized this property and used the plant for skin maladies. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Many plants had (and still have) multiple uses. Yaupon holly (Ilex vomitoria) leaves brewed as a highly caffeinated tea were used ceremonially and before warfare by many southeastern American Indian tribes, and then later by early American settlers when tea was difficult to import. Holly branches were used for arrows, and the bark for warding off nightmares. The purple passionflower, or maypop (Passiflora incarnata) vine attracts butterflies and produces a pulp used for syrups, jams, and drinks. Passionflower extract has also been developed into dozens of drugs and supplements for sedation.

Early civilizations living closer to the land knew many secrets that modern medicine has yet to unlock. Thanks to the ethnobotanists, the field and forest will continue to heal and provide for us for many generations yet to come.

CAUTION: Many of the plants listed or referenced can have hazardous or poisonous properties without appropriate preparation or dosage. Allergic reactions and prescribed drug interactions may occur, and many unproven rumors exist about medicinal uses of plants. Always consult a physician or health professional before trying supplements.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 5, 2017

This rain garden used stone for a berm and muhly grass as a decorative and functional plant. Photo credit, Jerry Patee

Tropical Storm Cindy’s early arrival soaked northwest Florida this month, followed by even more heavy rain. Homes in low areas and along the rivers flooded and suffered extensive damage. That being said, we are just entering our summer “rainy season,” so it may be wise to spend extra time thinking about adjusting your landscape to handle our typically heavy annual rainfall.

For example, if you have an area in your yard where water always runs after a storm (even a mild one) and washes out your property, you may want to consider a rain garden for that spot. Rain gardens are designed to temporarily hold rainwater and allow it to soak into the ground. However, they are quite different aesthetically from stormwater ponds, because they are planted with water-tolerant trees, shrubs, groundcovers and flowers to provide an attractive alternative to the eroding gully that once inhabited the area! Rain gardens are not “created wetlands,” but landscaped beds that can handle both wet and drier conditions. Many of the plants best suited for rain gardens are also attractive to wildlife, adding another element of beauty to the landscape.

A perfect spot for a rain garden might be downhill from a rain gutter, an area notorious for excess water and erosion. To build a rain garden, the rainwater leaving a particular part of the property (or rooftop), is directed into a gently sloping, 4”-8” deep depression in the ground, the back and sides of which are supported by a berm of earth. The rain garden serves as a catch basin for the water and is usually shaped like a semi-circle. The width of the rain garden depends on the slope and particular site conditions in each yard. Within the area, native plants are placed into loose, sandy soil and mulched. Care should be taken to prevent the garden from having a very deep end where water pools, rather allowing water to spread evenly throughout the basin.

This larger rain garden, or bioretention area, functions as stormwater treatment for a large parking lot in North Carolina. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF / IFAS Extension

Besides reducing a problematic area of the lawn, a rain garden can play an important role in improving water quality. With increasing populations come more pavement, roads, and rooftops, which do almost nothing to absorb or treat stormwater, contributing to the problem. Vegetation and soil do a much better job at handling stormwater. Excess sediment, which can fill in streams and bays, and chemicals from fertilizers and pesticides are just some of the pollutants treated within a rain garden via the natural growth processes of the plants.

A handful of well-known plants that work great in rain gardens include: Louisiana iris, cinnamon fern, buttonbush, Virginia willow, black-eyed Susan, swamp lily, tulip poplar, oakleaf hydrangea, wax myrtle, Florida azalea, river birch, holly, and Southern magnolia. For a complete list of rain garden plants appropriate for our area, visit the “Rain Garden” section of Tallahassee’s “Think about Personal Pollution” website.

For design specifications on building a rain garden, visit the UF Green Building site or contact your local UF IFAS County Extension office.

by Mary Salinas | Jun 22, 2017

‘Mel’s Blue’ Stokes’ Aster. Photo credit: Mary Derrick, UF/IFAS Extension.

Florida is home to some of the most beautiful flowering perennials. An exceptional one for the panhandle landscape is Stokes’ aster (Stokesia laevis) as it is showy, deer resistant and easy to care for. Unlike other perennials, it generally is evergreen in our region so it provides interest all year.

Upright habit and profuse blooming of ‘Mel’s Blue’ Stokes’ Aster. Photo credit: Mary Derrick, UF/IFAS Extension.

The original species of Stokes’ aster has purplish-blue flowers but cultivars have been developed with flowers in shades of white, yellow, rosy-pink and a deep blue. The flowers are large, eye-catching beauties that bloom in spring and summer. They also last well as a cut flower. You will find that bees and butterflies will appreciate their nectar! Remove spent flowers after blooms have faded in order to encourage repeat flowering.

A location in your landscape that provides part sun with well-drained rich soil is best for this perennial. Stokes’ aster is native to moist sites so it does best with regular moisture.

Stokes’ aster attracts butterflies like this black swallowtail. Photo credit: Mary Derrick, UF/IFAS Extension.

As with many perennials, the plant will form a large clump after a few years; this gives you the opportunity to divide the clump in the fall and spread it out in your landscape or share the joy with your gardening buddies.

For more information:

Gardening with Perennials in Florida

by Carrie Stevenson | Jun 15, 2017

Salt shear and onshore breezes often cause coastal maritime forests to grow at a slant away from the coast. Credit: Florida Master Naturalist Program

People from other parts of the country often move into Florida with expectations of their landscape beyond its capabilities. Those gorgeous peonies that grew up north or the perfect tomatoes they grew in California seem to wither in the heat or succumb to any number of insect or fungal pests. Adapting to our conditions takes listening to those with more experience, changing old habits or varieties and definitely adjusting expectations. Once you understand what the north Florida climate requires, you might be pleasantly surprised with a bumper crop of lemons or a thriving hibiscus that would never have worked in Michigan.

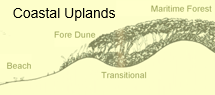

The same idea applies to landscaping on the beach or near areas of saltwater. Particularly on barrier islands like Perdido Key, Santa Rosa Island, and the coastal islands around Apalachicola, the influence of salt spray and hot, dry, sandy soils cannot be underestimated. If you have ever looked closely at the shape of the mature oak trees on the back sides of sand dunes, you’ll notice they’re shorter and tend to lean and grow away from the beach. This is due partially to the onshore breeze that steadily blows off the water, but also due to a phenomenon called salt shear. Salt shear occurs in areas where breaking waves release salt, which evaporates from water droplets and blows into the landscape. Unless specifically adapted to living in a saline environment, the salt can halt growth of the plants receiving the bulk of the spray. Many plants adapt to this by sealing up any vulnerable growing tips and sending energy for growth to the other side, resulting in a sloped shape. Land further inland from the Gulf will have consecutively less salt spray to endure.

Keep in mind that the soil on a barrier island is highly porous; it does not hold water nor nutrients well. The best option is to look at what grows there naturally, and select some of the most attractive and hardy choices for a home or commercial landscape. Knowing that a residence or commercial business is located within these environmental conditions, the best way to ensure success is to work with your surroundings instead of against them.

Below are a handful salt-tolerant options to consider.

Beach sunflower (Helianthus debilis): The yellow-blooming beach or dune sunflower will reseed and spread along as a hardy groundcover.

Muhly grass (Muhlenbergia capillaris): Muhly grass is a native clumping grass commonly used in Florida landscapes. It has showy pinkish-purple blooms in mid-fall.

Beach cordgrass (Spartina patens): Beach cordgrass is a native grass that serves as a sand stabilizer. While not particularly showy, it can serve as a good foundation plant.

Saw palmetto (Serenoa repens): These evergreen shrubs are extraordinarily hearty and long-lived. They produce a fruit that is an important food source for wildlife.

False rosemary (Conradina canescens): This evergreen shrub blooms purple, attracts wildlife, and is a hardy native species.

Firebush (Hamelia patens): Firebush has long-lasting red blooms that attract hummingbirds and native butterflies.

Blanketflower (Gaillardia pulchella): These colorful wildflowers attract pollinators like bees and butterflies and are extremely drought and salt tolerant.

Sunshine mimosa (Mimosa strigillosa): This ground-running plant has colorful, spherical pink blooms and attracts bees. The delicate leaves of the plant are sensitive to touch, and will fold up when touched.

For more information on salt-tolerant coastal plants and trees in our area along with cold-tolerant palms, contact your local Extension agent or Native Plant Society.