by Julie McConnell | May 23, 2018

Dr. Steve Johnson, UF/IFAS Associate Professor of Wildlife Ecology will be the featured speaker on June 6th

June 6th is a great day to learn about all types of invasive species that threaten natural areas in Northwest Florida!

The UF/IFAS Extension Bay County office will have multiple educational exhibits with living samples of species of concern from 9 a.m. – 5 p.m. on Wednesday, June 6th. This is a multi-agency effort to inform citizens about the impact of invasive plants and animals and how they can help reduce introduction and spread. For full details see the Bay_Invasive Workshop Flyer

We are pleased to announce our partners Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) and Science and Discovery Center of Northwest Florida will be on hand to share information about caring for exotic pets and current management plans for invasive species such as Lionfish, Aquatic Weeds, and how to surrender an animal on designated Pet Amnesty Days.

At noon there will be a special guest speaker for a bring your own lunch & learn “Exotic Invaders: Reptiles and Amphibians of Concern in NW FL.” Dr. Steven Johnson, UF/IFAS Associate Professor of Wildlife Ecology, will talk about exotic reptiles and amphibians we should be aware of that may occur in our area.

In the morning, we will be focusing on the invasive air potato vine with the distribution of air potato leaf beetles for biological control. Need air potato leaf beetles to manage the air potato vine on your property? Please register here http://bit.ly/bayairpotato to receive beetles – they will be distributed from 9 a.m. – noon on June 6th.

Learn more about the success of the Air Potato Biological Control program at http://bcrcl.ifas.ufl.edu/airpotatobiologicalcontrol.shtml

#invasivespecies

by Matt Lollar | Apr 23, 2018

Recently, an Extension Agent in the Florida Panhandle received a picture of some mushrooms popping up in a client’s garden. These particular mushrooms were in a spot where leftover mushroom compost had been dumped. The compost was previously used to grow oyster mushrooms and the client was hopeful that she had more oyster mushrooms growing in her yard. Unfortunately, the lab results came back stating the mushrooms in question were Armillaria spp.

Armillaria spp. in the garden. Photo Credit: University of Florida/IFAS Extension.

Armillaria spp. cause root rot of trees and shrubs throughout the world. The fungus infects the roots and bases of trees, causing them to rot and eventually die. Some species of Armillaria are primary pathogens that attack and kill plants, but most are opportunistic pathogens that are attracted to unhealthy or stressed plants. Fruiting structures of the fungi can be recognized by the clusters of yellow to brown-colored mushrooms that emerge during wet conditions. However, the mushroom caps sometimes never form and the plant material needs to be inspected more thoroughly to find the disease culprit. Infected plants may have wilted branches, branch dieback, and stunted growth and should be removed and replaced with resistant species.

White mycelial fan under the bark of a root infected with Armillaria tabescens. Photo Credit: Ed Barnard

Management – The best method for controlling Armillaria root rot is with proper plant installation and maintenance. Planting plant material at the proper depth will allow the roots to breathe and reduce the opportunity for the roots to rot. Pruning tools should be sanitized between plant material. Proper irrigation and fertilization will also reduce the risk of plant disease and root rot. Lastly, you can choose to plant a diverse landscape with resistant species.

For more information on Armillaria root rot and a comprehensive list of resistant species, please view the EDIS publication: Armillaria Root Rot

by Carrie Stevenson | Mar 26, 2018

Ah, the oft-ignored pine tree. They are so ubiquitous throughout the southeast, that many people consider them undesirable in a landscape. Having grown up near the “Pine Belt” of Mississippi, I figured I knew plenty about them, but this week I learned something new. While on a field tour with local foresters in the business of loblolly and longleaf pine farming, they introduced me to the pine tip moth. These insects can wreak havoc on valuable young pine trees.

Dead branch tip and needle damage caused by pine tip moths. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Hollow space in pine tree branch created by pine tip moth. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Female pine tip moths lay eggs on the growing end of a pine branch—particularly young, healthy loblolly and shortleaf (longleaf is rarely affected). When the eggs hatch 5-30 days later, the larvae start feeding. They tunnel into the shoot and bud of the pines, feeding on the tissue and burrowing a hollow cavity for several weeks. The larvae then pupate inside the space until becoming adult moths, exiting from the hole they created. The cycle restarts, with more adult moths, eggs and larvae.

Adult Nantucket pine tip moth Rhyacionia frustrana (Comstock). Photograph by James A. Richmond, USDA Forest Service, www.Forestryimages.org.

Two insect species are most common in our area; the subtropical pine tip moth (Rhyacionia subtropica) and Nantucket pine tip moth (Rhyacionia frustrana). The moths are reddish copper in color, small (1/2” wingspan and 1/4” body length) and active at night. Caterpillar larvae have black heads and start out with off-white bodies, but change in color to brown and orange as they age.

While this insect activity typically does not kill the tree, it does cause some die-off of terminal needles and branches. In extreme cases, it can cause tree death. Moths prefer younger trees and rarely affect pines taller than 15 feet.

If you see a cluster of dead needles at the ends of young pine branches of your property, you can easily snap off the dead tip. You will likely find the hollow space formed by the larvae, which in spring may still contain the insect. Treatment in a home landscape can managed by hand removal of infested shoots, but those in the commercial forestry business may need to install traps and consider insecticidal management.

Visit the UF School of Forest Resources and Conservation website for more information.

by Mark Tancig | Mar 26, 2018

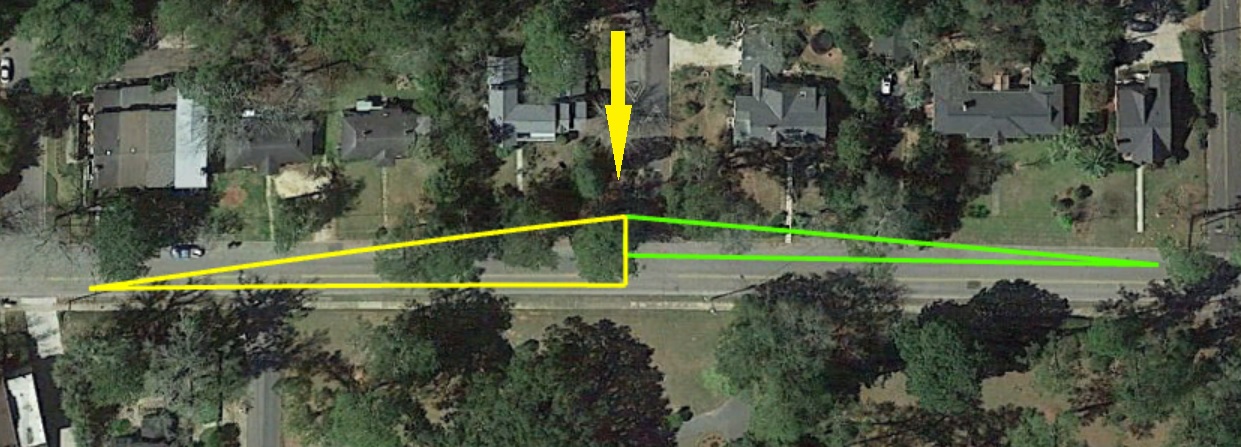

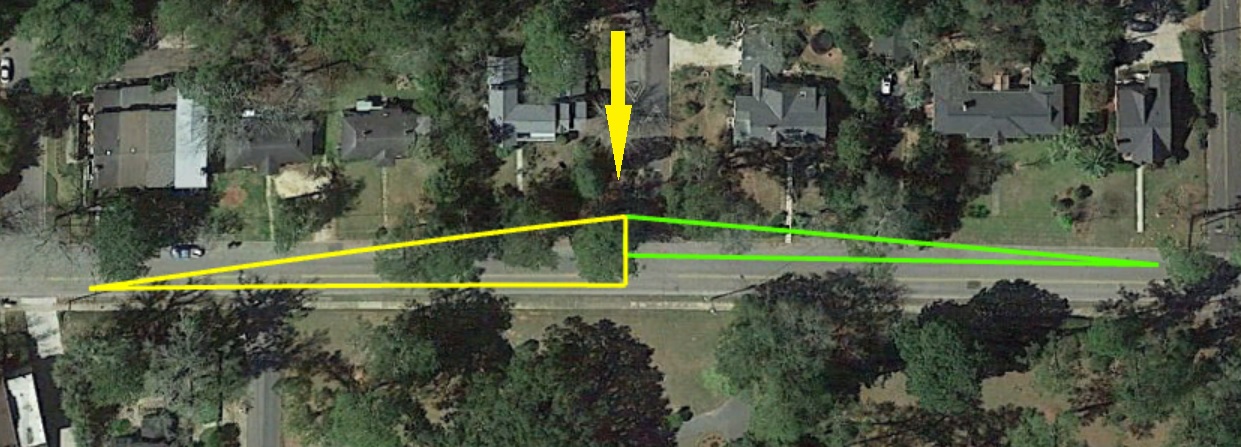

How many times have you pulled up to an intersection and couldn’t see oncoming traffic because a shrub was in the way? It’s frustrating, and unsafe. To help each other out, we should all pay attention to landscape plants that may be blocking the view of oncoming traffic and/or pedestrians, including your own driveway. Keeping a clear sight distance doesn’t mean you need a moonscape, but proper planning and maintenance of the landscape can look good and keep a clear sight distance.

“Site distance” is what traffic engineers call being able to see driving lanes and sidewalks, in both directions. I knew engineers had such a term and assumed they would have a precise way to measure it. Of course, since they’re engineers, they did. A local traffic engineer with the Leon County Public Works Department sent me the sketch. The figure should help, but, basically, you need to think of it as a sight triangles. The three points in each triangle are 1) the driver’s location at an intersection stop (where triangles meet), 2) the centerline of each lane, and 3) a point 300 – 500 down each lane. To determine if the view is clear, stand where a driver would stop, and approximate the height of the driver’s eye.

Please be safe as you rush to measure!

I can’t see if anyone’s coming! Credit: Mark Tancig/UF IFAS.

If you have vegetation in the way, assess the situation. First thing to determine is what plant(s) you have. If you don’t know, send a photo to your local Extension Office. Next, determine if the identified plant(s) can be pruned to get out of view and/or below the height of the driver’s eye. Transplanting to another location is a possibility, if it’s a plant that transplants well and isn’t too large. Otherwise, removing and replacing is the best option for the safety of the community.

When needing a low-growing replacement, consider the following Florida-Friendly plants:

African Iris (Dietes vegata) – Part Sun/Shade

Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia spp.) – Sun

Blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium angustifolium) – Part Sun/Shade

Butterweed (Packera glabella) – Shade

Coontie (Zamia florida) – Sun – Shade

Lily of the Nile (Agapanthus orientalis) – Part Sun/Shade

There are many, many more plants to choose from, including dwarf varieties of common ornamental plants. Your local Extension Office can help provide resources to help you make a good choice. Online resources, such as the Florida-Friendly Landscaping Pattern Books and the Guide to Plant Selection and Landscape Design, are also available.

by Carrie Stevenson | Mar 13, 2018

The swollen base and smooth gray bark of the swamp blackgum are identifying characteristics in wetlands. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

In the river swamps of northwest Florida, the first tree to come to mind is typically the cypress. The “knees” protruding from the water are eye-catching and somewhat mysterious. Sweet bay magnolia is an easily recognizable species as well, with its silvery leaves twisting in the wind. The sweet bay (Magnolia virginiana) is a relative of the Southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) in many of our yards, but its buds and leaves are smaller and it is found most often in very wet soils.

However, the often-unsung trees of the swamps are the tupelo and blackgum trees, including three species of Nyssa that go by a variety of overlapping common names. In the western Panhandle, one is most likely to see a swamp tupelo/swamp blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica var. biflora). The trees are tall—60-100’ at maturity—and have unremarkable elliptical green leaves. However, those leaves turn a lovely shade of red in the fall before dropping in the winter. Their most distinguishing characteristic year-round–but especially in the winter–is its swollen lower trunk, which expands at the base to twice or three times the size of the remaining trunk. These buttresses, also found on bays (more subtly) and cypress (along with knees), are an adaptation to stabilizing a tree growing in large pools of wet, loose soil or standing water.

A young blackgum tree in full fall color. Photo credit: UF IFAS Extension

The swamp tupelo has two more relatives in the region, water tupelo (Nyssa aquatica) and Ogeechee lime/tupelo (Nyssa ogeche), both with hanging edible (but tart) fruit. In the early days of William Bartram’s explorations of Florida, explorers used the acidic Ogeechee lime as a citrus substitute. Typically found in a narrower range from Leon County east to southeast Georgia, the Ogeechee lime is the nectar source for the famous and prized multi-million dollar tupelo honey industry.

Blackgum or tupelo trees (missing the “swamp” in front of their common name—aka Nyssa sylvatica) are actually excellent landscape trees that can thrive in home landscapes. Like their swamp cousins, the trees perform well in slightly acidic and moist soil, although they can thrive even in the disturbed, clay-based soils found in many residential developments. Blackgums can grow in full sun or shade, are highly drought tolerant, and can even handle some salt exposure. Their showy fall color is a nice addition to many landscapes, and the fruit are an excellent source of nutrition for native wildlife.

by Sheila Dunning | Feb 5, 2018

Pruning is one of the most controversial aspects of maintaining crapemyrtle. Traditionally, many crapemyrtles are routinely topped, leaving large branch and stem stubs. This practice has been called “crape murder” because of the potential impacts on the crapemyrtle health and structural integrity. Topping is the drastic removal of large-diameter wood (typically several years old), with the end result of shortening all stems and branches.

Pruning is one of the most controversial aspects of maintaining crapemyrtle. Traditionally, many crapemyrtles are routinely topped, leaving large branch and stem stubs. This practice has been called “crape murder” because of the potential impacts on the crapemyrtle health and structural integrity. Topping is the drastic removal of large-diameter wood (typically several years old), with the end result of shortening all stems and branches.

Hard pruning (topping) stimulates crapemyrtle sprouting from roots, upper stems, or the base of main stems. If basal and root sprouts are not removed, one or more may form woody stems that eventually compete with existing main stems. These additional or competing stems may result in poor form and structure, such as stems that rub against each other.

Topping typically delays flowering up to one month compared to unpruned crapemyrtle. On some cultivars, topping also shorten the season of bloom. Long-stem sprouts emerge just below large-diameter cuts that result from topping. These sprouts usually develop into upright, unbranched stems that eventually flower, often bending under their own weight. Rain or wind storms can cause extreme bending and some will break because they are weakly attached to the main stem.

Topping removes large amounts of starches and other food reserves stored within branches. Topping dramatically reduces the size of the plant canopy, ultimately decreasing the plant’s ability to produce food (starches) through photosynthesis. The large branch stubs caused by topping result in large areas of exposed wood that allow access by insects and wood-rotting organisms, weakening the plant’s structure. Finally, topping results in many dead stubs throughout the tree.

Proper pruning may be needed, just like any other tree. Lower limbs of crapemyrtle are removed to increase clearance for pedestrians or vehicles. Stems are cut to increase branching. Other pruning may be conducted to direct growth away from structures, stimulate flowering, and remove spent flowers, seed capsules, and dead or damaged branches and twigs.

Properly placed, crapemyrtle is a low-maintenance plant needing little or no pruning. Problems with overgrown, misshapen, or misplaced crapemyrtle can be greatly reduced with proper selection of crapemyrtle cultivars, proper plant selection at the nursery, and proper placement in the landscape. For more information on cultivar selection go to: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/mg266.

If pruning is necessary, use the following recommendations:

- Pruning for safety may be done anytime. This may involve removing damaged or weak branches or pruning lower limbs for pedestrian and vehicle clearance and visibility.

- Pruning to improve plant structure, redirect growth, or alter plant shape and appearance should occur when plants are leafless and dormant–typically December through February. Although this can be accomplished at any time, without leaves, the branching structure is clearly visible to more easily determine appropriate branches for pruning.

- Prune to remove crossing or rubbing branches.

- Prune dead, damaged, or diseased branches at the branch collar.

- Remove vigorous branches growing toward the center of the canopy.

- Severe pruning should be performed late in the dormant period. Pruning too early might stimulate new growth that could be damaged by low temperatures.