Video: Garden Success with Good Watering Practices

Success in the garden can occur with proper watering. Learn several ways to water to your vegetables In the Home Garden with UF IFAS Extension Escambia County.

Success in the garden can occur with proper watering. Learn several ways to water to your vegetables In the Home Garden with UF IFAS Extension Escambia County.

With our warm weather, many homeowners are looking to create a beautiful lawn for the year. There are so many products in the home improvement stores and nurseries that promise to make your lawn into a green paradise. What to choose?

Photo UF/IFAS Extension. Spring is a good time to check the water flow and direction of a pop-up irrigation system and make adjustments as necessary.

UF/IFAS Extension provides advice based on scientific research. This is what the science says:

The University of Florida provides more advice and information at:

There aren’t many more frustrating things than growing seemingly healthy tomatoes, those plants setting an abundance of flower and fruit, and then, once your tomatoes get about the size of a golf ball, having the fruit rot away from the base. This very common condition, called Blossom End Rot (BER), is caused one of two ways: by either a soil calcium deficiency or disruption of soil calcium uptake by the plant. Fortunately, preventing BER from occurring and then realizing an awesome crop of tasty tomato fruit is relatively simple and home gardeners have a couple of possible preventative solution!

Healthy ‘Big Beef’ tomatoes grown in 2019 with a pH of 6.5, amended with Gypsum at planting, and watered regularly each day! Notice no BER. Photo courtesy the author.

caused by calcium deficiency, it can be induced by creation of distinct wet and dry periods from non-regular watering, interfering with calcium uptake and availability to the plant. So, while you may have adequate soil calcium, if you don’t water correctly, the condition will happen anyway! It’s also good to keep in mind that mature tomato plants use large quantities of water daily, so during the heat of summer, plants in containers may need to be watered multiple times daily to maintain consistently moist soil. Think about it, you don’t drink 8 glasses of water when you wake up and then never drink again throughout a hot day. A tomato is no different. Allowing your plants to wilt down before providing additional water ruins productivity and can induce BER.

Blossom End Rot, while one of the more destructive fates of tomatoes, is totally preventable by a little legwork early in the growing game from you! Soil test and change pH with lime if needed, add a shot of calcium through a tomato blend fertilizer or non-lime supplement like gypsum, and water regularly! Do these three things and you’ll be well on your way to a great crop of early summer tomatoes. If you have any questions about tomato blossom end rot or any other horticulture or agricultural topic, please don’t hesitate to reach out to us at the UF/IFAS Calhoun County Extension Office. Take advantage of this beautiful spring weather and get in the garden today! Happy gardening.

For a state that receives around 60” of rainfall a year, it is sure dry in Florida right now! In the Panhandle, the majority of our annual rainfall occurs in in bunches during winter and early spring via near-weekly cold fronts, in the mid-summer as a result of afternoon thunderstorms, and periodically in late summer/early fall if a tropical system crosses our path. Mixed in, however, are two distinct, historically dry periods: the first one in April through mid-May (contrary to popular myth, if we have May flowers, they’re gonna have to make it without April showers) and the second right now in September and October. The prolonged second dry period that we’re experiencing now makes it difficult to manage the mostly unirrigated, low-input turfgrass common in rural Panhandle lawns and pastures. It is critical to enter these expected droughts with healthy turf and remembering to employ 3 simple management tips when it quits raining (although you should follow them year-round ideally) can greatly increase your turf’s resiliency!

Water Wisely – The average Florida turfgrass requires ¾-1” of water per week and we generally achieve that through rainfall. However, in our droughty months, supplemental irrigation can be a lawn saver, particularly in high traffic or more stressed areas of the yard. I realize that many of you, myself included, maintain large lawns without irrigation systems and it’s impossible to keep all your lawn well-watered during drought, but you can maintain the areas around your home, hardscapes and landscaped beds with the highest impact/visibility nicely! In these areas, put down no more than ¾” of water per irrigation event, a ballpark number that ordinarily allows the turf root zone to become saturated. Measuring your sprinkler’s water output is easily done by setting several straight-sided cans (tuna or cat food containers work great) under the sprinkler and timing how long it takes to achieve 3/4”. You might be surprised how much water you waste by leaving a sprinkler running for an hour or more!

Apply Herbicides Appropriately – Herbicides are a great item to have in the turf care toolbox, but if used incorrectly can be a waste of time and money at best, harmful to your turf at worst! Once turf and associated weeds become drought stressed (turning bluish gray, obvious wilting, leaves curling, etc.), it is too late for weed control with herbicides. There are a couple of reasons for this. First, when plants get stressed, they slow or stop their growth and focus on survival. This survival response prevents herbicides from being taken up properly and ultimately causes ineffectual weed control. Also, many herbicides specifically state on the product label that they should not be applied during certain conditions (drought, temperatures above 85-90 degrees, etc.). It is critical that one adhere to these label directions as applying the incorrect product in hot and dry conditions can cause volatility, drift to non-target plants, and in some cases, toxicity to turf you’re treating in. When it’s droughty like it is now, leave the herbicides in the chemical shed to prevent wasting your time and money and potentially damaging non-target plants!

Raise that Deck – Finally, one of the most important turf management strategies during an extended drought is to reduce mowing and raise your mower’s cutting height when/if you do mow. As mentioned above, plants are already stressed during a drought and physically chopping off a chunk of the turf plant stresses it further, causing an energy-intensive wound response when the plant is actively conserving resources for survival. Therefore, if you just HAVE to mow, raise the cutting height as high as possible to make the smallest injury possible on the grass and keep your mower blades sharp to ensure a clean cut, which will heal easier and require a smaller energy response from the plant.

During droughts like the one we’re currently in, there isn’t one silver bullet to keep your non-irrigated turf looking good. However, there are several strategies you can use throughout the year to get your lawn through dry times. Remember to water ¾”-1” per week when you can, where you can. Before you water, calibrate your sprinkler to ensure you put out enough water and don’t waste your time and inflate your utility bill by putting out too much! Reduce or eliminate use of herbicides as they are ineffective during stress periods and can harm your turfgrass. Finally, reduce or eliminate mowing and if you must mow, raise the deck! If you have any questions about getting your turf through the drought or other horticultural or agronomic topics, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Office!

Last week at the Panhandle Fruit and Vegetable Conference, Dr. Ali Sarkhosh presented on growing pomegranate in Florida. The pomegranate (Punica granatum) is native to central Asia. The fruit made its way to North America in the 16th century. Given their origin, it makes sense that fruit quality is best in regions with cool winters and hot, dry summers (Mediterranean climate). In the United States, the majority of pomegranates are grown in California. However, the University of Florida, with the help of Dr. Sarkhosh, is conducting research trials to find out which varieties do best in our state.

In the wild, pomegranate plants are dense, bushy shrubs growing between 6-12 feet tall with thorny branches. In the garden, they can be trained as small single trunk trees from 12-20 feet tall or as slightly shorter multi-trunk (3 to 5 trunks) trees. Pomegranate plants have beautiful flowers and can be utilized as ornamentals that also bear fruit. In fact, there are a number of varieties on the market for their aesthetics alone. Pomegranate leaves are glossy, dark green, and small. Blooms range from orange to red (about 2 inches in diameter) with crinkled petals and lots of stamens. The fruit can be yellow, deep red, or any color in between depending on variety. The fruit are round with a diameter from 2 to 5 inches.

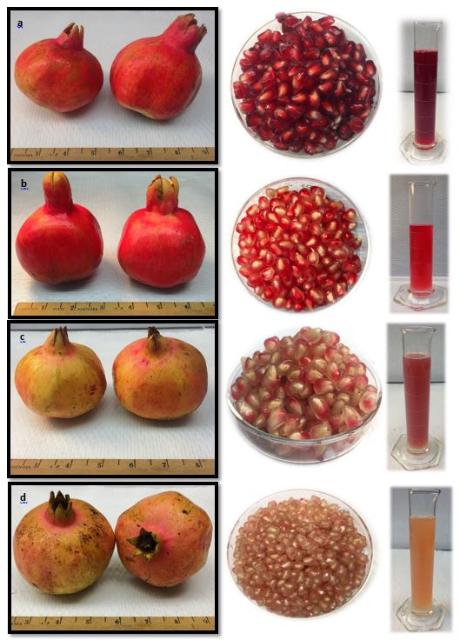

Fruit, aril, and juice characteristics of four pomegranate cultivars grown in Florida; fruit harvested in August 2018. a) ‘Vkusnyi’, b) ‘Crab’, c) ‘Mack Glass’, d) ‘Ever Sweet’. Photo Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, University of Florida/IFAS

A common commercial variety, ‘Wonderful’, is widely grown in California but does not perform well in Florida’s hot and humid climate. Cultivars that have performed well in Florida include: ‘Vkusnyi’; ‘Crab’; ‘Mack Glass’; and ‘Ever Sweet’. Pomegranates are adapted to many soil types from sands to clays, however yields are lower on sandy soils and fruit color is poor on clay soils. They produce best on well-drained soils with a pH range from 5.5 to 7.0. The plants should be irrigated every 7 to 10 days if a significant rain event doesn’t occur. Flavor and fruit quality are increased when irrigation is gradually reduced during fruit maturation. Pomegranates are tolerant of some flooding, but sudden changes to irrigation amounts or timing may cause fruit to split.

Two pomegranate training systems: single trunk on the left and multi-trunk on the right. Photo Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, University of Florida/IFAS

Pomegranates establish best when planted in late winter or early spring (February – March). If you plan to grow them as a hedge (shrub form), space plants 6 to 9 feet apart to allow for suckers to fill the void between plants. If you plan to plant a single tree or a few trees then space the plants at least 15 feet apart. If a tree form is desired, then suckers will need to be removed frequently. Some fruit will need to be thinned each year to reduce the chances of branches breaking from heavy fruit weight.

Anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum sp. to pomegranate fruit. Photo Credit: Gary Vallad, University of Florida/IFAS

Anthracnose is the most common disease of pomegranates. Symptoms include small, circular, reddish-brown spots (0.25 inch diameter) on leaves, stems, flowers, and fruit. Copper fungicide applications can greatly reduce disease damage. Common insects include scales and mites. Sulfur dust can be used for mite control and horticultural oil can be used to control scales.

Seldom do we find the answer to a problem as being easy. More often, a difficult and complicated answer is what’s needed. However, the solution to a healthy lawn rebound may be found simply by adjusting your mower height and mowing schedule.

Mowing strategy is an important variable that keeps a lawn healthy and flourishing, no matter the species or cultivar of grass. Mowing too high can lead to an undesirable look and cause unwanted thatch buildup, which can create a favorable environment for pests and diseases. Mowing too low can weaken the root system causing thinning, which allows space for weeds to invade. Another problem with mowing too low is that it affects nutritional needs. Lawn grasses generate food for themselves through a process called photosynthesis. A healthy leaf surface area is needed to effectively accomplish this. If the lawn is mowed too low, then leaf surface area is lost. The grass can literally starve itself.

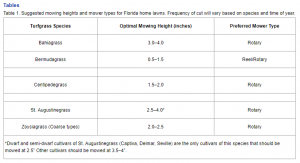

Table: Suggested mowing height for lawn grasses. Frequency of cut will vary based on species and time of year. Credit: L. E. Trenholm, J. B. Unruh & J. L. Cisar, UF/IFAS Extensio

Not all lawn grasses should be mowed at the same height, as show in the table above. Fine textured grasses like Bermuda and Zoysia matrella can be cut significantly lower than coarse textured grasses, such as Bahia or St. Augustine. Not sure of the type of lawn grass you have? Visit this site https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/topic_book_florida_lawn_handbook_3rd_ed to review the Florida Lawn Handbook or contact your local county extension office for questions.

Mowing schedule is the other side of the coin. How often to mow ultimately depends on how fast your grass grows. By nature, Bermuda will grow quickly and Zoysia is somewhat slower growing. Regardless, summer months are when warm-season lawn grasses grow more rapidly. Historically, lawn grasses begin a dormant-slow growth stage in October and continues through March. Fertilizer schedule also plays a role in grass growth rate. So how often do you need to mow? This rate is best determined by the amount of growth since the last cutting, rather than the number of days which have elapsed. You should mow often enough so that no more than 1/4 to 1/3 of the total leaf surface is removed at any given mowing. In other words, leave twice as much leaf surface as you cut off. Remember, incremental adjustments should be made to your current practices. Never drastically change the height of the grass. If the lawn has been allowed to grow too long, you should gradually lower the mowing height on successive cuttings.

What are some other helpful tips? Always use a well-adjusted mower with a sharpened blade. You may find it easier replace your blade each year or every 2 years than periodic resharpening. Dull mower blades do a tremendous amount of damage with uneven cuts. This will cause gashes and splits in the leaf where fungal and bacterial pathogens can thrive. Never mow grass when it’s wet, either. Dry grass cuts are cleaner cuts and won’t clog the mower deck. If you have built up thatch, it’s a good idea to attach a bag to your mower that will catch clippings. These clippings will be great additions to your compost pile or to use as natural mulch. If no thatch problems exist, mowing without a bag will distribute clippings throughout the lawn, and the clippings will decompose into nutrients for the root system.

With proper mowing strategies, along with fertilizing & watering, your lawn grass can bounce back. For more information contact your local county extension office.

Information for this article provided by the UF/IFAS Extension EDIS Publication, “Mowing Your Florida Lawn”, by L. E. Trenholm, J. B. Unruh & J. L. Cisar: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/LH/LH02800.pdf

UF/IFAS Extension is an Equal Opportunity Institution.