by Danielle S. Williams | Mar 4, 2021

Shiranui mandarin

You’ve likely seen them in the grocery stores, and you’ll see them now through April. A large, lumpy (some may say ugly) piece of orange fruit with a bump near the stem. But what exactly is this special looking fruit? It’s a Shiranui mandarin!

The name ‘Shiranui’ is the generic term for this variety of citrus. You may have seen the same variety of mandarin marketed in grocery stores as ‘Sumo Citrus’ which is a trademarked name for the variety. In Japan, they are widely known as ‘Dekopons’. No matter what you call them, they are easily recognized by their distinctive appearance.

The Shiranui mandarin is a hybrid between a Ponkan tangerine and a Kiyomi Tangor (sweet orange x satsuma mandarin). They are easy to peel, sweet, and seedless. Shiranuis are considered to be one of the sweetest and most flavorful varieties of citrus on the market. The fruit are large and have a large protruding bump near the stem that resembles the top knot hairstyle of a Japanese sumo wrestler (hence the trademarked name ‘Sumo Citrus’).

While the majority of Shiranui mandarins on the market are grown in California, the variety can be grown here in Florida and several citrus growers in North Florida and South Georgia have began to experiment with plantings in the region. Homeowners, too, can try their hand at growing the variety as many Florida certified citrus nurseries carry the variety. For more information on different citrus varieties, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Agent.

by Matt Lollar | Feb 18, 2021

It’s mid-February, cloudy, and cold. It’s time to get outside and take cuttings for fruit and nut tree grafting. The cuttings that are grafted onto other trees are called scions. The trees or saplings that the scions are grafted to are called rootstocks. Grafting should be done when plants start to show signs of new growth, but for best results, scion wood should be cut in February and early March.

Scion Selection

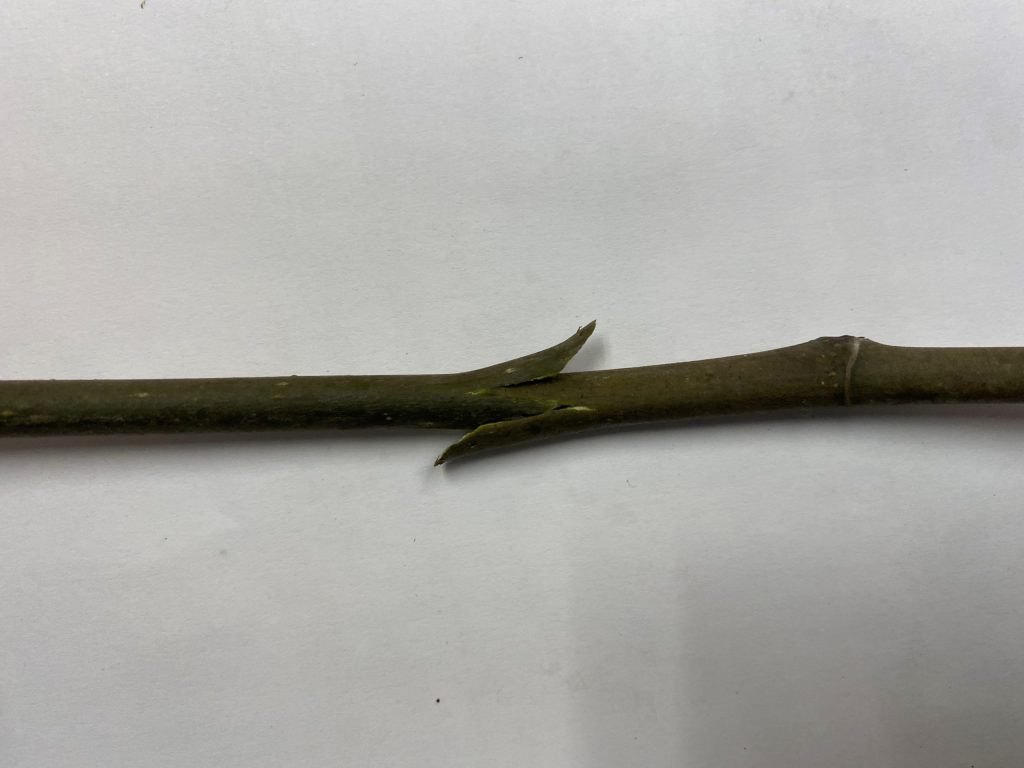

Straight and smooth wood with the diameter of a pencil should be selected for scions. Water sprouts that grow upright in the center of trees work well for scion wood. Scions should be cut to 12-18″ for storage. They should only need two to three buds each.

Scions ready for grafting. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

Scion Storage

Scions should be cut during the dormant season and refrigerated at 35-40°F until the time of grafting. If cuttings are taken in the field or far from home, then simply place them in a cooler with an ice pack until they can be refrigerated. Cuttings should be placed in a produce or zip top bag along with some damp paper towels or sphagnum moss.

Grafting

It is better to be late than early when it comes to grafting. Some years it’s still cold on Easter Sunday. Generally, mid-March to early April is a good time to graft in North Florida. Whip and tongue or bench grafting are most commonly used for fruit and nut trees. This type of graft is accomplished by cutting a diagonal cut across both the scion and the rootstock, followed by a vertical cut parallel to the grain of the wood. For more information on this type of graft please visit the Grafting Fruit Trees in the Home Orchard from the University of New Hampshire Extension.

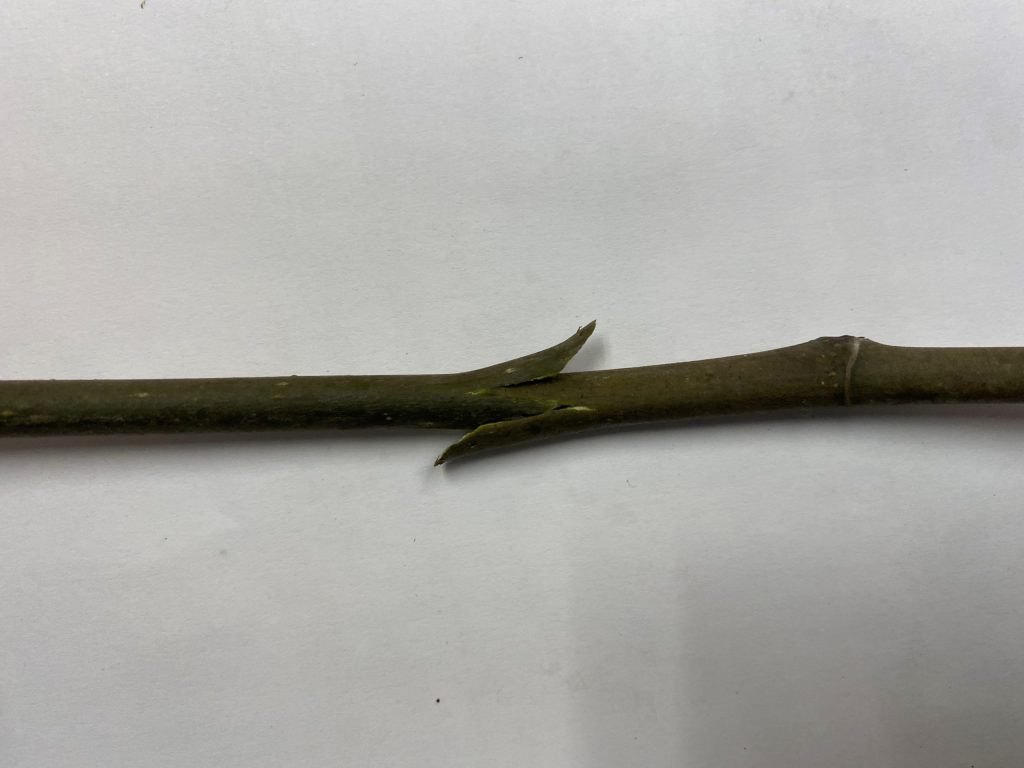

A bench graft union. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

Achieving good bench graft unions takes skill and some practice. Some people have better success using a four-flap or banana graft technique. This type of graft is accomplished by stripping most of the bark and cambium layer from a 1.5″ section of the base of the scion and by folding the back and removing a 1.5″ section of wood from the top of the rootstock. A guide to this type of graft can be found on the Texas A&M factsheet “The Four-Flap Graft”.

Grafting is a gardening skill that can add a lot of diversity to a garden. With a little practice, patience, and knowledge any gardener can have success with grafting.

by Ray Bodrey | Nov 4, 2020

Who doesn’t like strawberries, right? Backyard gardeners grow these low-growing herbs throughout the state and there is a significant commercial industry too, as Florida’s climate is ideal for cool season production.

Strawberries like well-drained sandy soils, so they’re a perfect fit for many areas in the Panhandle. Strawberries should be planted in the months of October or November as the plants are quite cold hardy. Shorter days and temperatures between 50°F and 80°F are ideal for fruit development.

Photo Credit: Cristina Carriz, UF/IFAS

Strawberries are also very versatile. You can plant them in the ground, in raised beds or even containers. Transplants should be planted 12” to 18” apart, with 12” row spacing. For best results, use a rich soil balanced with compost and sandy soil and both fertilize and water regularly. Mixing in 2 ½ pounds of 10-10-10 fertilizer into a 10’ x 10’ bed space should be sufficient to start. A sprinkle of fertilizer applied monthly throughout the growing season should also help ensure a solid yield.

Berry production begins to ramp up roughly 90 days after planting, but plants will continue to produce throughout the spring. When the weather gets warmer, the plants start to expend energy into producing runners instead of fruit. These runners will be new fruit producing plants for next season.

Transplants can be purchased from most garden centers. There are many varieties on the market, but “Florida-Friendly” cultivars include “Sweet Charlie”, “Camarosa”, “Chandler”, “Oso Grande”, “Selva”, and “Festival”. “Camarosa” has proven to be the most productive variety in North Florida. Any of these varieties are capable of producing two pints of fruit per plant.

As stated earlier, Florida has a significant strawberry industry and UF/IFAS has a supporting role. The UF/IFAS Gulf Coast Research and Education Center (GCREC) is home to the Strawberry Breeding Program. Cultivars are developed by traditional means, for the Florida commercial industry on an 11,000+ acres research site. Appearance, shelf life, sweet flavor and disease resistance are just some of the areas of selected breading research that is conducted on site. There is also a white strawberry soon to be released!

Photo Credit: Cristina Carriz, UF/IFAS

For more information, contact your local county extension office.

Supporting information for this article can be found at the website: https://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/plants/edibles/fruits/strawberries.html

UF/IFAS Extension is an Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Matt Lollar | Nov 4, 2020

From time to time we get questions from clients who are unsatisfied with the flavor of the fruit from their citrus trees. Usually the complaints are because of dry or fibrous fruit. This is usually due to irregular irrigation and/or excessive rains during fruit development. However, we sometimes get asked about fruit that is too sour. There are three common reasons why fruit may taste more sour than expected: 1) The fruit came from the rootstock portion of the tree; 2) The fruit wasn’t fully mature when picked; or 3) the tree is infected with Huanglongbing (HLB) a.k.a. citrus greening or yellow dragon disease.

Rootstock

The majority of citrus trees are grafted onto a rootstock. Grafting is the practice of conjoining a plant with desirable fruiting characteristics onto a plant with specific disease resistance, stress tolerance (such as cold tolerance), and/or growth characteristics (such as rooting depth characteristics or dwarfing characteristics). Citrus trees are usually true to seed, but the majority of trees available at nurseries and garden centers are grafted onto a completely different citrus species. Some of the commonly available rootstocks produce sweet fruit, but most produce sour or poor tasting fruit. Common citrus rootstocks include: Swingle orange; sour orange; and trifoliate orange. For a comprehensive list of citrus rootstocks, please visit the Florida Citrus Rootstock Selection Guide. A rootstock will still produce viable shoots, which can become dominant leaders on a tree. In the picture below, a sour orange rootstock is producing a portion of the fruit on the left hand side of this tangerine tree. The trunk coming from the sour orange rootstock has many more spines than the tangerine producing trunks.

A tangerine tree on a sour orange rootstock that is producing fruit on the left hand side of the tree. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension

Fruit Maturity

Florida grown citrus generally matures from the months of October through May depending on species and variety. Satsumas mature in October and taste best after nighttime temperatures drop into the 50s. Most tangerines are mature in late November and December. Oranges and grapefruit are mature December through April depending on variety. The interesting thing about citrus fruit is that they can be stored on the tree after becoming ripe. So when in doubt, harvest only a few fruit at a time to determine the maturity window for your particular tree. A table with Florida citrus ripeness dates can be found at this Florida Citrus Harvest Calendar.

Citrus Greening

Citrus Greening (HLB) is a plant disease caused by the bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus, which is vectored by the Asian citrus psyllid. The disease causes the fruit to be misshapen and discolored. The fruit from infected trees does not ripen properly and rarely sweetens up. A list of publications about citrus greening can be found at the link Citrus Greening (Huanglongbing, HLB).

A graphic of various citrus greening symptoms. Photo Credit: University of Florida/IFAS Extension

by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 1, 2020

Ripe figs are a deep shade of pink to purple. Larger green figs will ripen in a few days. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

Summer is full of simple pleasures—afternoon rainstorms, living in flip flops, and cooling off in a backyard pool. Among these, one of my favorites is walking out my door and picking handfuls of figs right from the tree. Before we planted our tree, my only prior experience with the fruit was a Fig Newton—I’d never eaten an actual fig, much less one picked fresh. Now, they are my favorite fruit.

Native to Asia Minor and the Mediterranean, figs were introduced to Florida in the 1500’s by Spanish explorers. Spanish missionaries introduced these relatives of the mulberry to California a couple hundred years later. Figs are best suited to dry, Mediterranean-type climates, but do quite well in the southeast. Due to our humidity, southern-growing figs are typically fleshier and can split when heavy rains come through. The biggest threats to the health of the trees are insects, disease (also due to our more humid climate) and root-knot nematodes.

Fig trees can grow quite large and produce hundreds of fruit each year. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

Our tree started out just a couple of feet tall, but 15 years ago we replanted it along a fence in our back yard. It grew so large (easily 25 feet tall and equally wide) that it hangs over our driveway, making it handy to grab a few as I head out for a walk or hop in the car to run errands. The tree is in full sun at the bottom of a slope, and seems to be a satisfied recipient of all the runoff from our backyard. This position has resulted in a thick layer of soil and mulch in which it thrives. In the last year, we pruned it down to an arms-reach height so that we could actually get to the figs being produced.

We usually see small green fruit start to appear in early May, becoming fat and ripe by the second half of June. The tree produces steadily through early August, when the leaves turn crispy from the summer heat and there’s no more fruit to bear. The common fig doesn’t require a pollinator, so only one tree is necessary for production. The fiber-rich fig is also full of calcium, potassium, and vitamins A, E, and K. As it turns out, the “fruit” is actually a hollow peduncle (stem) that grows fleshy, forming a structure called a synconium. The synconium is full of unfertilized ovaries, making a fig a container that holds both tiny flowers and fruit in one.

The insides of a fig show the small flowering structures that form the larger fruit. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

With the hundreds of figs we’ve picked, my family has made fig preserves, fig ice cream, baked figs and of course eaten them raw. We typically beg friends and neighbors to come help themselves—and bring a ladder—because we can’t keep up with the productivity. The local birds and squirrels are big fans, too. Often you can tell you’re near our tree from around the block, as the aroma of fermenting fruit baking on the driveway is far-reaching.

No matter what you do with them, I encourage planting these trees in your own yard to take full advantage of their sweet, healthy fruit and sprawling shade. As Bill Finch of the Mobile (AL) botanical gardens has written, “fresh…figs are fully enjoyed only by the family that grows them, and the very best figs are inevitably consumed by the person who picks them.”