by Rick O'Connor | Dec 10, 2021

By Dr. Steve A. Johnson, Department of Wildlife Ecology & Conservation, University of Florida

As I was pondered writing about snakes for Panhandle Outdoors, an email notification appeared on my computer screen: “Snake in Pensacola Bay”. As a State Extension Specialist with the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences I receive a lot of email requests to identify snakes and other reptiles. But the subject line of this message really got my attention because most of Florida’s approximately 50 species of native snakes are terrestrial, and with few exceptions, our aquatic snakes only occur in freshwater. Florida is home to one snake that lives in the marine environment, the Saltmarsh Watersnake (Nerodia clarkii), but they inhabit shorelines and rarely stray far from cover. And sea snakes are only found the Pacific Ocean basin—they do not naturally occur in the Gulf of Mexico.

Eastern Coachwhips are long and thin, and most adults have a dark head and upper body. The rest of the body is tan or brown and the scale pattern on the tail resembles a braided bullwhip. Photo by Nancy West.

With anticipation I opened the email and viewed the attached images. To my surprise the snake seen by a fisherman who “came across a snake swimming out in the middle” of Pensacola Bay was an Eastern Coachwhip (Masticophis flagellum). In my almost 20 years with the University of Florida I’ve been emailed hundreds of times with requests to identify snakes. Although the coachwhip is a fairly common snake in Florida, its rarely the species I’m asked to identify. But I distinctly remember another email about 10 years ago from a gentleman in southeastern Florida who claimed he had killed a deadly Taipan snake, or at least something that looked to him like a Taipan. He told me he had lived in Florida for 30 years and knew how to identify snakes, but he had never seen a native snake that looked like this. There are three recognized species of Taipans, they are all native to Australia and are among the world’s most venomous land snakes. However, Florida is the global epicenter for introductions of non-native reptiles, due mainly to imports for the exotic pet reptile trade, so I did not immediately dismiss his assertion of Taipan, but I was highly suspect. Fortunately, the image attached to the email was not a Taipan. But unfortunately, it was an Eastern Coachwhip that he needlessly killed. Coachwhips are not venomous and are certainly not deadly of even dangerous, unless you are a lizard.

The dark head and upper body followed by a tan color allowed positive identification of this snake in Pensacola Bay as an Eastern Coachwhip. Photo by David Celko.

Coachwhip snakes are closely related to the Black Racer, the common “black snake” of the Southeast. Like racers, coachwhips are long, thin snakes with relatively large eyes. In fact, the Eastern Coachwhip is one of the longest native snakes in North America, reaching a maximum length of 8.5 feet, including the tail. The head and upper body of adult Eastern Coachwhips are usually dark brown or black, fading to brown or tan the rest of the length of their thin body. The scales on their tail resemble the braided pattern of a bullwhip, which is where they get their common name of coachwhip. Young Eastern Coachwhips are also tan colored, but they lack the dark head and upper body. The large eyes are especially obvious in young coachwhips.

Juvenile Eastern Coachwhips are quite thin and have large eyes. They lack the dark-colored head and upper body of most adults. Photo by Dr. Steve A. Johnson, UF/IFAS.

In northern peninsular Florida adult Eastern Coachwhips may lack a dark-colored head and upper body. Photo by Dr. Steve A. Johnson, UF/IFAS.

Eastern Coachwhips actively forage for lizards during the day, and they also eat small mammals, birds, frogs, and even small turtles. While hunting for prey they often move about with their head raised above the ground, visually searching for signs of movement. Eastern Coachwhips have a strong bite, which is how they subdue larger prey—they do no kill prey by constriction like do rat snakes. Coachwhips are fast snakes and can crawl more than 3.5 mph. When startled they often rapidly escape into a burrow or climb into a shrub or small tree. At night they shelter in burrows made mammals as well as the Gopher Tortoise.

The author holding a (dead) highly venomous Taipan in far north Queensland, Australia. Even in very remote places, roads and vehicles are a source of snake mortality. The Taipan resembles the Eastern Coachwhip of Florida, but taipans only occur in Australia. Photo by Dr. Todd Campbell, University of Tampa.

Like all Florida’s snakes, Eastern Coachwhips are threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation by roads. Coachwhips move around a lot, and often get smashed by vehicles. So do the right thing and “give a snake a brake” the next time you see one attempting to cross a road. And certainly, never kill an Eastern Coachwhip on purpose as they are not venomous and don’t pose any danger to people or pets.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 10, 2021

Most people would agree that this is one of the best times of the year. Christmas brings great music, great cooking, great family gatherings, and… great lights. The lighting of Christmas is one of the more beautiful parts of these celebrations and as I thought about Christmas and writing about nature I thought of those lights.

There is nothing like Christmas lights on a tree.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Nature can produce beautiful lights as well. Mostly found in the ocean – “phosphorus”, as many called it when I was growing up here, is a beautiful spectacle. It is hard to see with our artificial lights but in the warmer months of summer at locations far from the artificial lights of people, the sea glows a blue-green color that is amazing. Many see this light as sparkles in the water as the waves roll by. Others see it as a stream of light as a fish, or something else, moves around. In the right conditions, you can see your footprints glow as you step in the wet sand. I remember diving at night under the Bob Sikes Bridge once in the 1970s when the bridge, and all of the divers, were aglow. It was beautiful. This phenomena have amazed scientists for centuries and trying to understand how it is produced was a quest for many.

The term phosphorescence actually means using light to emit light. Turns out that is not what is happening in this case. Scientists found that some creatures posses a group of molecules known as luciferins. The term lucifer means “producing light” or “morning star” and seemed an appropriate name for this group of molecules. When luciferin is oxidized, the transfer of an electron emits a “cool light” – usually blue-green in color. Cool meaning that less than 20% of the emitted light is lost as heat. There is a catalytic enzyme known as luciferase that can increase the speed of this chemical reaction and produce bright light in seconds. Since this light is produced by a chemical reaction it was called “chemiluminescence”. However, since this reaction is produced and controlled by living organisms is more widely known as “bioluminescence”. It is not phosphorescence.

Bioluminescence in the sea.

Photo: North Carolina Sea Grant

There are many creatures that produce bioluminescence. The famous fireflies are one, but most live in the sea. The “phosphorus” we are used to seeing is produced by small single celled plants in a group known as dinoflagellates. When disturbed they emit blue-green light as a flash and then a slow dim. Fish swimming past, waves crashing on the beach, or boat and propeller pushing through the water will disturb them. The warmer the sea, the more dinoflagellates there are, the more amazing the light show is. There are lagoons in the tropical parts of the world where these small plants are trapped due to a small opening in and out of the lagoon. The entire lagoon can light up when the conditions are right.

Noctiluca are one of the dinoflagellates that produce bioluminescence.

Photo: University of New Hampshire.

But it does not stop with dinoflagellates. As you descend into the deep ocean the bioluminescence becomes even more spectacular. All sorts of creatures from jellyfish to squid, to fish, to even fungus and bacteria illuminate. Some species of luminescent marine animals do not produce the light themselves but rather harbor luminescent bacteria on the skin or specially designed skim pockets to hold them. Though blue-green is the dominant color, yellows, oranges, and reds have been produced. It has been suggested that blue-green is much easier to see in the deep so reds and oranges are less likely. That said, it is believed that some marine creatures will produce those colors to assist in capturing prey. They can see the red light, but their prey cannot.

The magical lights of the deep sea.

Photo: NOAA

Either way the illumination of the ocean, like the Christmas illumination of our streets and homes, is beautiful and amazing thing. As you admire the lights on the neighborhood home, find some short videos of bioluminescence online and enjoy the show. Happy Holidays everyone.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 10, 2021

Hoese and Moore1 describes members of the frogfish family as “grotesque”. Well… maybe. I am not sure I would call them grotesque, but they are sort of gelatinous blobs with reduced or missing scales. They feel sort of “mushy”. They have broad shaped fins and a free dorsal spine that serves as a “fishing rod and lure” called the illicium. Maybe they are a little grotesque…maybe.

Being round with broad fins, this is a very slow swimming fish, if you can call how they move swimming. So, to survive, they must blend in with the environment to avoid predators and wait for their prey to come within range before pouncing on them. The illicium lures prey to within range and their “gulp” is like a vacuum cleaner sucking food out of the water.

The family name for the group is Antennariidae, which is appropriate being they have that fishing lure, and is one of the few fish families whose gill opens are behind the pectoral fin. There are 48 species of frogfish found worldwide and most are tropical and subtropical2. Hoese and Moore1 indicate there are three species found in the Gulf of Mexico and all three can be found along the Florida panhandle.

The most commonly encountered frogfish in our area is the Sargassum fish (Histro histro). This small six-inch fish blends in perfectly with the sargassum mats that float in close to shore. Using its fins to brace itself in the seaweed, this fish uses its illicium to attract a variety of small prey that live in the sargassum community. As the sargassum mats are blown close to shore the sargassum fish will leave and move to another mat further out. Finding them on the beach is rare but snorkeling out to a mat just offshore with a small hand net, you might be able to find one by scooping up some sargassum and taking a look.

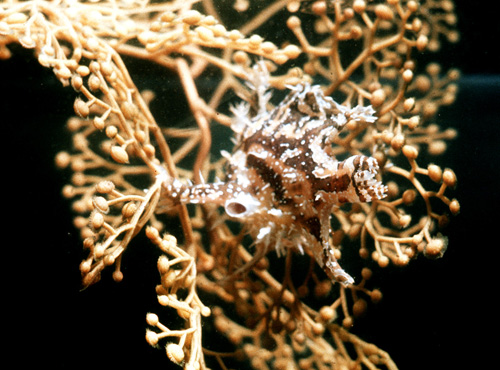

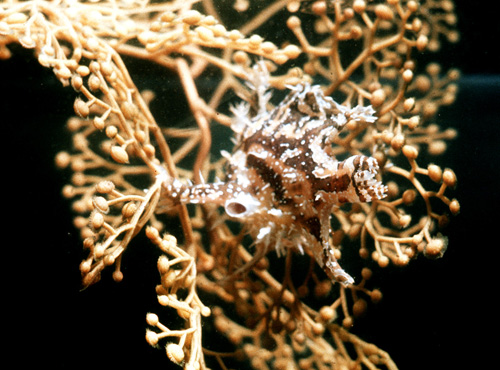

This sargassum fish is well camelflouged within this mat of sargassum weed.

Photo: Florda Museum of Natural History

The Singlespot Frogfish (Antennarius radiosus) is even smaller at three inches and is found on hard habitats of the middle continental shelf offshore, but occasionally is found along the coastline.

The Splitlure Frogfish (Phrynelox scaber) is five inches in length and not as common on our shelf as the singlespot frogfish. Those that have been found off our coast were further offshore.

The Florida Museum of Natural History includes the Striated Frogfish (Antennarius striatus) as a Gulf species and resident of panhandle waters3.

The distribution of this group is pretty wide throughout the tropical and subtropical waters of the Atlantic Ocean and beyond – suggesting few geographic barriers to dispersal. The sargassum fish, of course, is restricted where sargassum is found – but sargassum is found in a lot of places. The singlespot frogfish seems to have a more restricted home range found in Bermuda, the Atlantic coast of Georgia and Florida, and the Gulf of Mexico. Hoese and Moore does not report this fish in other parts of the Caribbean as the others are1.

They may be grotesque to some, but to others it is an amazing group of fish, much fun in an aquarium, and exciting to find when snorkeling or diving.

1 Hoese H.D., Moore R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M University. College Station TX. Pp. 327.

2 Family Antennariidae – Frogfish. 2012. FishBase. https://www.fishbase.de/summary/FamilySummary.php?ID=192.

3 Antennarius striatus. 2017. Discover Fishes. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/antennarius-striatus/.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 2, 2021

This series on vertebrates of the Florida panhandle is to enhance your education of the different animals that call this place home. This is the only reason to include clingfish to this list… to enhance your education.

There are about 500 species of fishes in the northern Gulf of Mexico. We I began this series I had no intention of writing about all of them. I was going to focus on the more common and familiar, such as snappers and mackerels. Things like the clingfish were to be skipped over. But when I saw this family next on the list, I could not skip over this one. You see, this is actually a pretty common fish that you many have already encountered and followed by asking “what kind of fish is this?” So, we will include our friend the clingfish.

Clingfish

Photo: University of Washington

It belongs to the family Gobiesocidae and, in the northern Gulf of Mexico, there is only one resident species, Gobiesox strumosus, known as the clingfish or skilletfish. They are called this because their body shape resembles a cast iron skillet, roundish head with an extended tail and dark in color. The often-used clingfish name comes from the sucker apparatus they form on the ventral side of their body to cling to rocks and inside of shells – where they are most often found. Hoese and Moore1 report only one species from the northern Gulf but suggest there could be more on the offshore reefs.

The local skilletfish is reported to reach a mean length of three inches. I have only seen a few of these and the ones I found were smaller than this. They are dark in color, often with stripes or streaks, and can be all black – the ones I have found were all black. The ones I have found are inside dead oyster shells associated with oyster reefs. You may find a random oyster clump on the bottom. You just pick it up, look inside the opened shells and open the dead shells, and you may find one. They have been reported associated with rocks, pipes, and other structures on the bottom.

This species does have a large geographic range, suggesting few barriers to dispersal. They are found from New Jersey to Brazil and throughout the Gulf of Mexico.

There is no commercial value for the animal, no cool natural history facts, just an small fish that you may come across while playing in the Gulf that you might ask – “what kind of fish is this?” Now you know, it’s the clingfish.

Reference

1 Hoese, H. D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Northern Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 2, 2021

Six Rivers “Dirty Dozen” Invasive Species

Red Fire Ant (Solenopis invicta)

The red imported fire ant.

Photo: University of Florida Entomology and Nematology

Define Invasive Species: must have all of the following –

- Is non-native to the area, in our case northwest Florida

- Introduced by humans, whether intentional or accidental

- Causing either an environmental or economic problem, possibly both

Define “Dirty Dozen” Species:

These are species that are well established within the CISMA and are considered, by members of the CISMA, to be one of the top 12 worst problems in our area.

Native Range:

The red fire ant is a native of central South America.

Introduction:

It is believed the first red fire ants entered the U.S. from Brazil into either Mobile AL or Pensacola FL between 1933 and 1945 via ship. As of 2008 they had been reported in 16 states stretching from the east to the west coast, albeit mostly southern states.

EDDMapS currently list 799 records of red fire ants in the U.S. This is certainly well under reported. Most of these are from the southeastern United States (including Texas) and three records from the Washington/Oregon area. There are only 15 records from Florida, 6 from the panhandle, and no records within the Six Rivers CISMA. Again, this is significantly underreported to EDDMapS. It is a well-known species in our area.

Description:

The body of the red imported fire ant is red brown in color with a black gaster (tail). The thin/skinny “waist” has two segments. The mounds are usually of soil and, if disturbed, aggressively defended by the colony. They like well-manicured lawns and in Florida’s sandy soils, may not form the large mounds found in clay-based soils. They differ from the native fire ant (Solenopsis geminate) in that workers of the native species have enlarged square heads – not found in the invasive red imported fire ant.

Issues and Impacts:

The red imported fire ant has become a pest for agriculture and urban communities alike. They can cause both medical and environmental harm.

In agriculture the ant is known to infest soybean fields. Large infestations can lower crop yield, and some states report large infestations impacting the ability to use combines for harvest, reducing yield. One paper reported $156 million in losses with the soybean industry. The ants will feed on the young developing plants of not only soybean but okra, cabbage, citrus, corn, bean, cucumber, eggplant, potato, sweet potato, peanut, sorghum, and sunflower crops. They are also a pest for livestock.

In urban communities they will nest almost anywhere including sidewalks, lawns, driveways, mailboxes, along the sides of homes. During heavy rains they will seek higher ground sometimes entering houses and forming floating mats of live ants that have been problems after storm events. The sting is quite painful. Ants will both bite with their mandibles and inject a venom with a spine on their gaster. The venom is an alkaloid mixture that exhibits potent necrotoxic activity (destroys tissue). The reactions to fire ant stings vary depending on the individual from mild pain to anaphylactic shock. The actual medical cost from the fire ant invasion is unknown. Not only do they sting humans, but pets as well. Fire ants have been found in electrical systems and have caused short circuiting.

These ants have had an impact on native wildlife as well. Ground nesting birds and rodents will cease in areas where the ants colonize, and it is known that they have impacted the protected gopher tortoise populations.

Management:

There are two plans of attack on fire ant management but no long term effective method is known. (1) individual mounds, (2) wide area broadcast application.

Individual Mound

- Liquids poured over the mound can be effective. These liquids can be hot water or insecticide products mixed with water. There are numerous fire ant insecticides available. However, if the queen is not killed (living deep in the mound), recolonization is probable.

- Dusting involves sprinkling an insecticide dust over the mound, and then watering it in.

- Mound injections is an option. Here tools are used to inject the insecticide into the mound. This can be more expensive and hazardous to the handler.

- Baits can be placed on the mound where the colony spreads it through out. This can be very effective but slow going.

- There are certain mechanical and electrical devices on the market, but their efficacy is not well tested.

Some suggest that only 20% of a colony is feeding at any one time and that many insecticides are not as effective. The timing of the control is important. Comprehensive fire ant management information can be found in the Extension publication, Managing Imported Fire Ants in Urban Areas.

Broadcast Applications

Most of the broadcast sprays involve baits or dust products. They can be effective but are often sprayed in locations where the ants cannot find them or become inactive by the time they do.

Biological Control

Biological controls using native predators must be tested to assure they do not have a negative impact on the native flora and fauna. Two potential biological controls, a protozoan and a fungus, are currently being tested along with others.

Phorid flies (which are parasites on fire ants) have been released in the southeast U.S. by the USDA. These colonies of flies have expanded beyond the area where they were released.

Home Remedies

Home remedies including club soda, grits, soap, wood ashes, and shoveling mounds together have shown to be ineffective.

For more information on this Dirty Dozen species, contact your local extension office.

References

Red Imported Fire Ant. Solenopsis invicta. Featured Creatures. University of Florida Entomology and Nematology. https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/urban/ants/red_imported_fire_ant.htm.

Fire Ants. University of Florida IFAS Gardening Solutions. https://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/care/pests-and-diseases/pests/fire-ants.html.

Fire Ants in Florida. University of Florida Blogs. https://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/lawn-and-garden/fire-ants-in-florida/.

Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System (EDDMapS)

https://www.eddmaps.org/

Six Rivers CISMA

https://www.floridainvasives.org/sixrivers/