by Sheila Dunning | Jan 28, 2021

Groundhog

Groundhog Day is celebrated every year on February 2, and in 2021, it falls on Tuesday. It’s a day when townsfolk in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, gather in Gobbler’s Knob to watch as an unsuspecting furry marmot is plucked from his burrow to predict the weather for the rest of the winter. If Phil does see his shadow (meaning the Sun is shining), winter will not end early, and we’ll have another 6 weeks left of it. If Phil doesn’t see his shadow (cloudy) we’ll have an early spring. Since Punxsutawney Phil first began prognosticating the weather back in 1887, he has predicted an early end to winter

only 18 times. However, his accuracy rate is only 39%. In the south, we call also defer to General Beauregard Lee in Atlanta, Georgia or Pardon Me Pete in Tampa, Florida.

But, what is a groundhog? Are gophers and groundhogs the same animal? Despite their similar appearances and burrowing habits, groundhogs and gophers don’t have a whole lot in common—they don’t even belong to the same family. For example, gophers belong to the family Geomyidae, a group that includes pocket gophers, kangaroo rats, and pocket mice. Groundhogs, meanwhile, are members of the Sciuridae (meaning shadow-tail) family and belong to the genus Marmota. Marmots are diurnal ground squirrels. There are 15 species of marmot, and groundhogs are one of them.

Science aside, there are plenty of other visible differences between the two animals. Gophers, for example, have hairless tails, protruding yellow or brownish teeth, and fur-lined cheek pockets for storing food—all traits that make them different from groundhogs. The feet of gophers are often pink, while groundhogs have brown or black feet. And while the tiny gopher tends to weigh around two or so pounds, groundhogs can grow to around 13 pounds.

While both types of rodent eat mostly vegetation, gophers prefer roots and tubers while groundhogs like vegetation and fruits. This means that the former animals rarely emerge from their burrows, while the latter are more commonly seen out and about. In the spring, gophers make what is called eskers, or winding mounds of soil. The southeastern pocket gopher, Geomys pinetis, is also known as the sandy-mounder in Florida.

Southeastern Pocket Gopher

The southeastern pocket gopher is tan to gray-brown in color. The feet and naked tail are light colored. The southeastern pocket gopher requires deep, well-drained sandy soils. It is most abundant in longleaf pine/turkey oak sandhill habitats, but it is also found in coastal strand, sand pine scrub, and upland hammock habitats.

Gophers dig extensive tunnel systems and are rarely seen on the surface. The average tunnel length is 145 feet (44 m) and at least one tunnel was followed for 525 feet (159 m). The soil gophers remove while digging their tunnels is pushed to the surface to form the characteristic rows of sand mounds. Mound building seems to be more intense during the cooler months, especially spring and fall, and slower in the summer. In the spring, pocket gophers push up 1-3 mounds per day. Based on mound construction, gophers seem to be more active at night and around dusk and dawn, but they may be active at any time of day.

Pocket Gopher Mounds

Many amphibians and reptiles use pocket gopher mounds as homes, including Florida’s unique mole skinks. The pocket gopher tunnels themselves serve as habitat for many unique invertebrates found nowhere else.

So, groundhogs for guesses on the arrival of spring. But, when the pocket gophers are making lots of mounds, spring is truly here. Happy Groundhog’s Day.

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 16, 2020

That’s the question from a recent group exploring what washed up on the beach after Hurricane Sally.

Sea Cucumber

Photo by: Amy Leath

They have no eyes, nose or antenna. Yet, they move with tiny little legs and have openings on each end. Though scientists refer to them as sea cucumbers, they are obviously animals. Sea cucumbers get their name because of their overall body shape, but they are not vegetables.

There are over 1,200 species of sea cucumbers, ranging in size from ¾“ to more than 6‘ long, living throughout the world’s ocean bottoms. They are part of a larger animal group called echinoderms, which includes starfish, urchins and sand dollars. Echinoderms have five identical parts to their bodies. In the case of sea cucumber, they have 5 elongated body segments separated by tiny bones running from the tube feet at the mouth to the opening of the anus. These squishy invertebrates spend their entire life scavenging off the seafloor. Those tiny legs are actually tube feet that surround their mouth, directing algae, aquatic invertebrates, and waste particles found in the sand into their digestive tract. What goes in, must come out. That’s where it becomes interesting.

Sea cucumbers breathe by dilating their anal sphincter to allow water into the rectum, where specialized organs referred to as respiratory trees (or butt lungs) extract the oxygen from the water before discharging it back into the sea. Several commensal and symbiotic creatures (including a fish that lives in the anus, as well as crabs and shrimp on its skin) hang out on this end of the sea cucumber collecting any “leftovers”.

But, the ecosystem also benefits. Not only is excess organic matter being removed from the seafloor, but the water environment is being enriched. Sea cucumbers’ natural digestion process gives their feces a relatively high pH from the excretion of ammonia, protecting the water surrounding the sea cucumber habitats from ocean acidification and providing fertilizer that promotes coral growth. Also, the tiny bones within the sea cucumber form from the excretion of calcium carbonate, which is the primary ingredient in coral formation. The living and dying of sea cucumbers aids in the survival of coral beds.

When disturbed, sea cucumbers can expose their bony hook-like structures through their skin, making them more pickle than cucumber in appearance. Sea cucumbers can also use their digestive system to ward of predators. To confuse or harm predators, the sea cucumber propels its toxic internal organs from its body in the direction of the attacker. No worries though. They can grow them back again.

Hurricane Sally washed the sea cucumbers ashore so you could learn more about the creatures on the ocean floor. Continue to explore the Florida panhandle outdoor.

by Sheila Dunning | Jul 16, 2020

Credits: Clemson University, www.insectimages.org

The hickory horned devil is a blue-green colored caterpillar, about the size of a large hot dog, covered in long black thorns. They are often seen feeding on the leaves of deciduous forest trees, such as hickory, pecan, sweetgum, sumac and persimmon. For about 35 days, the hickory horned devil continuously eats, getting bigger and bigger every day. In late July to mid-August, they crawl down to the ground to search for a suitable location to burrow into the soil for pupation. While the hickory horned devil is fierce-looking, they are completely harmless. If you see one wandering through the grass or across the pavement, help it out by moving it to an open soil surface.

The pupa will overwinter until next May to early-June, at which time, they completely metamorphosize into a regal moth (Citheronia regalis). Like most other moths, it is nocturnal. But, this is a very large gray-green moth with orange wings, measuring up to 6 inches in width. It lives only about one week and never get to eat. In fact, they don’t even have a functional mouth. Adults mate during the second evening after emergence from the ground and begin laying eggs on tree leaves at dusk of the third evening. The adult moth dies of exhaustion. Eggs hatch in six to 10 days.

Adult regal moth, Citheronia regalis (Fabricius).Credits: Donald W. Hall, UF/IFAS

The regal moth, and its larvae stage called the hickory horned devil, is native to the southeastern United States. The damage they do to trees in minimal. Learning to appreciate this “odd” creature is something we can all do. For more information: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/IN/IN20900.pdf

by Rick O'Connor | May 27, 2020

As we continue our series on marine life in the Gulf of Mexico, we also continue our articles on marine worms. Worms are not the most charismatic creatures in the Gulf, but they are very common and play a large role on how life functions in this environment. Roundworms are VERY common. There are at least three phyla of them but here we will focus on one – the nematodes.

A common nematode.

Photo: University of Florida

Most nematodes are microscopic, a large one would be about 2 inches, and some beach samples have found as many as 2 million worms in 10 ft2 of sand. So, what do we know about them? What role, or function, do they play in the ecology of the Gulf of Mexico?

Well first, they are long and round – cylinder shaped. There is a head end, but it is hard to tell which end is the head. Round is considered a step up from being flat in that it can allow for an internal body cavity. An internal body cavity can allow for the development of internal body organs. Internal body organs can move large amounts of nutrients, blood, oxygen, and hormones around the body allowing the animal to become larger. Some argue that a larger body can have advantages over smaller ones. Some say the opposite, but either way – a large body has been successful for some creatures and an internal body cavity is needed for this.

That said, the nematodes do not have a complete internal body cavity. So, they do not have a complete assortment of internal organs. Being round reduces your efficiency in absorbing enough needed nutrients, oxygen, etc. through your skin alone and this MAY be a reason they are small. They are very small.

There are free living and parasitic forms in this group. There are at least 10,000 species of them, and they can be found not only in the marine environment, but also in freshwater and in the soil found on land. They have played a role in the success of agriculture, infesting both crops and livestock. Nematodes can be a big concern for farmers and gardeners.

The free-living forms are known to be carnivorous, feeding on smaller microscopic creatures. They have toothed lips, and some have a sharp stylet to grab or stab their prey. Some stylets are hollow and can “suck” their prey in. Moving through the environment, they can consume algae, fungi, and diatoms. Some are deposit feeders and others are decomposers. On our farms and in our gardens, they are known to enter plants via the roots and can be found in the fruit.

The life cycle of the human hookworm.

Image: CDC

The parasitic version of nematodes has been a problem for some species. In humans we have the hookworms and pinworms. Dogs have their heart worms. An interesting twist on the parasitic nematode way of life, compared to flatworms like tapeworms, is their lack of a secondary (or intermediate host). The entire life cycle can take place in the same animal.

Females are larger than males and fertilizations is internal. Males are usually “hooked” at the tail end and hold on to the females during mating. About 50 eggs will be produced and released into the digestive tract, where they exit the animal in the feces and find new hosts either by the feces being consumed or drifting in the water column.

There multiple forms of parasitism in nematodes.

– Some are ectoparasites (outside of the body) on plants.

– Some are endoparasites in plants – some forming galls on the leaves.

– Some infest animals but only as juveniles.

– Some live-in plants as juveniles and animals as adults.

– Some live-in animals as juveniles and plants as adults.

It would be fair to say that many forms of marine creatures have nematodes living either within them, or on them. Some can be problematic and cause disease; some diseases can be quite serious. Others play an important role in “cleaning” the ocean, filtering the sand of organic debris. Many have heard of nematodes but know little about them. Either good or bad, they do play roles in the ecology of the Gulf of Mexico.

by Carrie Stevenson | May 22, 2020

Sea pork comes in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Recently I was walking the beach, enjoying a sunset and looking around at the shells and other oddities in the wrack line where waves deposit their floating treasures. Something bright green and oblong caught my eye. It was emerald in color, smooth yet fuzzy at the same time, and firm to the touch. At first, I thought it was a sea bean–a collective term for the many species of seeds and fruits that float to our shores from tropical locations in the Caribbean or Central/South America. The bright green definitely seemed like something botanical in nature. However, the vast majority of sea beans have a woody, protective shell similar to our more familiar pecans or acorns.

I remembered a family member asking about finding a mystery chunk of pink mass she found on the beach a few years ago. It resembled a pork chop more than anything else.

A different variety of sea pork that really lives up to its name. Photo credit: Stephanie Stevenson, Duval County Master Gardener

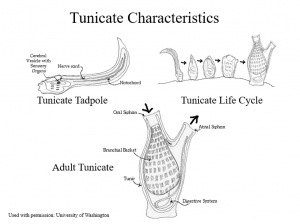

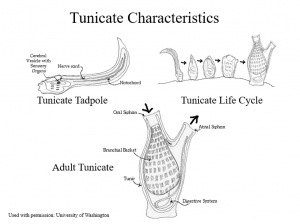

Looking closer and consulting a couple of resources, I realized we had both (most likely!) happened upon one of the oddest and often-questioned finds on our beaches: sea pork. Ranging in color from beige and pale pink to red or green, sea pork is a tunicate (or sea squirt), a member of the Phylum Chordata, home to all the vertebrate and semi-vertebrate animals. While they look and feel more like a cross between invertebrate slugs or sponges, the tunicates are more advanced organisms, possessing a primitive backbone in their larval “tadpole” form. Despite their blob-like appearance, they are more closely related to vertebrate animals than they are to corals or sponges.

The unusual life cycle of the tunicate. Photo credit: University of Washington, used with permission with Florida Master Naturalist program

During their short (just hours-long) larval stage, the tunicate larvae uses its nerve cord (supported by a notochord similar to a vertebrate spine) to communicate with a cerebral vesicle, which works like a brain. Similar to fish, this primitive brain uses an otolith to orient itself in the water, and an eyespot to detect light. These brain-like tools are utilized to locate an appropriate location to settle permanently. Using a sticky substance, the tunicate will attach its head directly to a hard surface (rocks, boats, docks, etc.) and go through a metamorphosis of sorts. The tunicate reabsorbs its tail and starts forming the shape and structure it needs for adulthood.

As an adult, the organism has a barrel shape covered by a tough tunic-like skin (hence “tunicate”). Adult bodies have two siphons, one to bring water in, another to shoot it out (giving them their other nickname, the sea squirt). The water passes through an atrium with organs that allow it to filter feed, trapping plankton and oxygen. The tunicates will spend most of their lives attached to a surface, pumping water in and out as filter feeders. They may be solitary or live in colonies, and vary widely in color and shape, lending variety to those chunks of sea pork found washing up.

I am still awaiting positive identification from an expert on my green find to confirm that it is, indeed, a tunicate and not an unfamiliar plant. Consulting with Extension colleagues, for now we are pretty confidently going with green sea pork. If you have seen one of these before or something resembling sea pork, let us know! It is fascinating to see the variety and unusual shapes and colors.

.

by Carrie Stevenson | May 15, 2020

Crawfish boils are popular in the springtime. Crawfish are generally harvested from aquaculture operations. Photo credit: Libbie Johnson, UF IFAS Extension

“You get a line, I’ll get a pole, we’ll go down to the crawdad hole, honey, baby, mine“…there are lots of great zydeco songs singing the praises of crawfish (aka crayfish, crawdads, mudbugs). They are in season now, and while crawfish festivals all around the southeast are canceled due to concerns over COVID-19, they are still available and make for great eating. Most of us would recognize a cooked one alongside a feast of corn and potatoes, but would you know an actual crawfish hole if you came up on it?

Last fall, our office welcomed about 500 kids (over several days) to the 4-H camp in Barrineau Park for a field trip. I showed every single one of them a small muddy mound with an opening in the top, and asked if anyone could tell me what it was. Not a single kid knew! Now, I make sure I point crawfish mounds out to anyone I happen to be walking with, as they are fascinating little structures. Also referred to as crawfish chimneys due to their upright, open construction, they are built by a crawfish in a muddy area, often near a creek or other water source.

Crawfish mounds are constructed using small pellets of mud, and the opening connects down to a burrow. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

The industrious invertebrate uses its legs and mouth to create pellets of mud as it digs its burrow. It places mud up above the ground, using the mud balls like small bricks. Bricking up the entrance to its burrow (as opposed to placing discarded mud elsewhere) also protects a crawfish from exposure to predators on open soil. The crawfish chimneys can be 6 inches tall (or more!) and connect down to a burrow that may reach 3 feet deep, some straight down and others with side tunnels extending different directions.

Since the crawfish lives in wetland areas, it is theorized that these chimneys extending above the soil allow for better oxygen flow in the burrow. During a drought, crawfish will plug the opening of their mounds with mud, to keep water in the burrow from evaporating.

Crawfish in the wild are rarely harvested, although some folks do fish for them like the song referenced earlier. For the vast majority of crawfish harvested in commercial production, two species are the most popular–the white river crawfish (Procambarus zonangulus) and red swamp crawfish (Procambarus clarkii). They are typically farmed in coordination with rice, as both commodities thrive in flooded conditions. Most aquaculture operations are associated with Louisiana, but at least five other southern U.S. states farm crawfish. To learn more about this industry, check out LSU AgCenter’s informative video.