by Rick O'Connor | Mar 7, 2025

The principles of life on land are not that different from life in the sea. It is believed that life began in the sea but, the creation of continents and islands, new habitat was available for colonization. However, the creatures who would colonize land would have to have different characteristics than those in the sea.

Frogs are land animals that use water environments as well.

Photo: U.S. Geological Survey

A limiting factor for the producers in the sea was light. Sunlight is the energy that fuels the process of photosynthesis. Thus, the producers had to either live in shallow water or be able to stay near the surface of the sea in order to function. For MOST locations on land, sunlight is not the issue. In fact, in some locations, too much sunlight can be an issue. You need sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to photosynthesize – and on land, water would be the hardest to obtain. Many land creatures actually still live in water part time. There are rivers, lakes, and streams crossing over the landscape that can provide suitable habitat for both producers and consumers. However, most of the landscape is not water and photosynthesizing plants – like trees, grasses, and shrubs – developed root systems to absorb water from the ground.

Forest and trees are plants that have adapted to obtaining water from the ground.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Another player in this game are the swirling ocean currents. As they rotate past the polar regions of the world, they become colder. As the cold currents pass land, they lower the humidity and produce less rainfall. Drier conditions meant plants had to adapt to both the issue of over evaporation and sufficient groundwater to support them. Desert plants have done just that. Often along mountain ranges the mountainside closest to the ocean, or warm currents will produce the greatest amount of precipitation. While the opposite will be drier and more desert like. The producers who live on each side of the mountain will be different due to this. Landscapes near warm ocean currents are humid and rainfall is high. Here the landscape is lush and green with some of the highest plant diversity found on the planet.

Deserts are found in locations where rainfall and humidity are low.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Land dwelling consumers follow suit. They must first be able to deal with the amount of sunlight, temperature fluctuations, and humidity as the planets do. Then the primary consumers – those that feed on the producers – must be able to feed on the plants that have adapted to that area.

Deer are land animals that have adapted to several climates and feeding on land plants.

Photo: Carolina Baruzzi.

These climate conditions have formed what biologists call biomes – ecologically unique ecosystems. Examples of biomes are deserts, grasslands, alpine forests, hardwood forests, swamps, marshes, and more. Each possesses their unique plant and animal communities. And – like the systems found in the sea – they are constantly changing. Life on land has to deal with the seasons of the year more than those in the oceans do. Prey evolve to defend themselves from predators. Predators evolve to overcome these new defenses. Some species are very successful, others have gone extinct. Though large-scale climate changes – such as ice ages and warming periods – impact life in the sea, they tend to be more impactful for life on land.

Polar bears have adapted to harsh conditions on land.

Photo: NOAA

Biogeography is the study of how creatures disperse across the landscape (or ocean), meet barriers, and define their biological range. Some creatures have large areas where they are found – such as seagulls, squirrels, and raccoons. These are called cosmopolitan species. Others have very small ranges – such as the marine iguana, Komodo dragon, and kangaroos – and are referred to as endemic species. There are many plants and animals that dispersed across North America and can be found on both coasts. Others are only found in one small area of the country. In our next article we will introduce one species that has dispersed across the entire planet – humans.

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 21, 2025

They say life began in the oceans. We know that the lithosphere is cracked, adding new land, subducting land over time. But much of the lithosphere is covered with water – and here life began. Initially it had to begin on either rock or sand. The sand would have been produced by the weathering and erosion of rock. Obviously, this would all have had to occur over a long period of time. But the first forms of life would have to be able to find food and nutrition from a barren seafloor with little to offer. This would take a special community of creatures – ones we call the pioneer community.

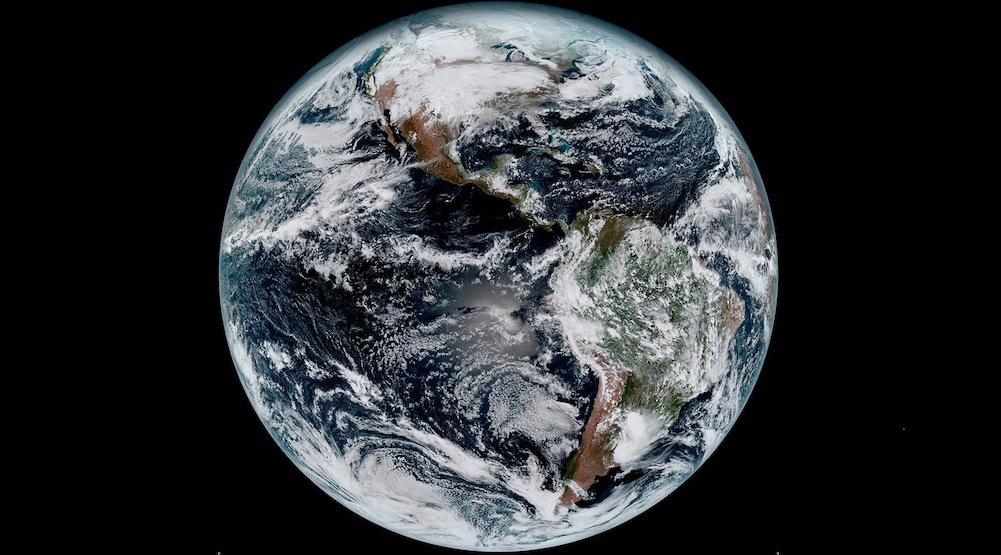

It is believed that life began in the ocean.

Phot: Rick O’Connor

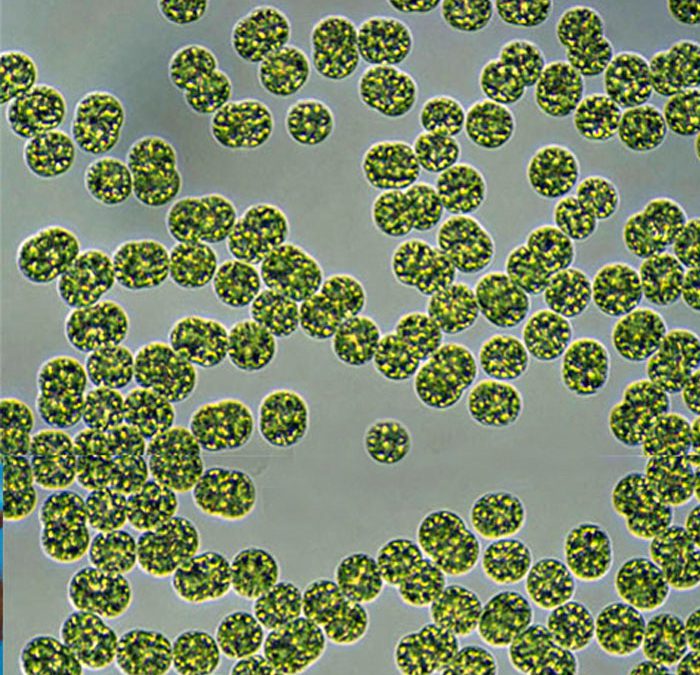

Key members of these communities would have been the producers’ ones who produce food. What we know now is that producers absorb carbon dioxide and water and – using the sun as a source of energy – convert this into carbohydrates and oxygen. We have since learned that there are ancient forms of bacteria that can do this with hydrogen sulfide and other compounds. However, it started – it began. One problem with this model is that much of the world’s oceans are too deep for sunlight to reach. Thus, living organisms would need to be close to shore. Today we know two things. One, the ocean’s surface is covered with microscopic plant-like creatures (phytoplankton) who can float and reach the sunlight. Two, some of the ancient chemosynthetic bacteria (those that do not need the sun and can use other compounds to produce carbohydrates) live on the ocean floor.

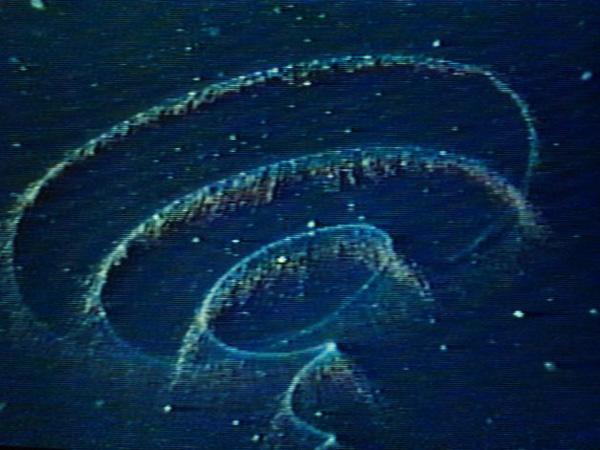

The black smokers – hydrothermal vents – found on the ocean floor.

Photo: Woodshole Oceanographic Institute.

Producers are followed by consumers, creatures who cannot make their own food and must feed on either the producers or on other consumers. There are plankton feeding animals – oysters, sponges, corals, and zooplankton. There are larger creatures that feed on larger plankton – manta rays, menhaden, and whales. There are consumers who feed on the first order of consumers – stingrays, parrotfish, and pinfish. And there are the top predators – orcas, sharks, and tuna. The ocean is a giant food web of creatures feeding on creatures. All creatures evolve defenses to avoid predation. Predators evolve answers to these defenses. Some species survive for long periods of time like the horseshoe crabs and nautilus. Others cannot compete and go extinct.

Horseshoe crabs are one of the ancient creatures from our seas. Photo: Bob Pitts

As we mentioned in Part 1 of this series – the hydrosphere is in motion. Different temperatures, pressure, and the rotation of the planet move water all over. These currents bring food and nutrients, remove waste, and help disperse species across the seas. Life spreads to other locations. Some conditions are good – and life thrives. Others not so much – and only specialists can make it. The biodiversity of our oceans is an amazing. Coral reefs, mangrove forests, and seagrass beds are home to thousands of species all interacting with each other in some way. The polar regions are harsh – but many species have evolved to live here, and the diversity is surprising higher than most think. The bottom of the sea is basically unknown. It has been said we know more about the surface of the moon than we do at the bottom of our ocean. But we know there is a whole world going on down there. We believe the basic principles of life function there as they do at the surface – but maybe not!

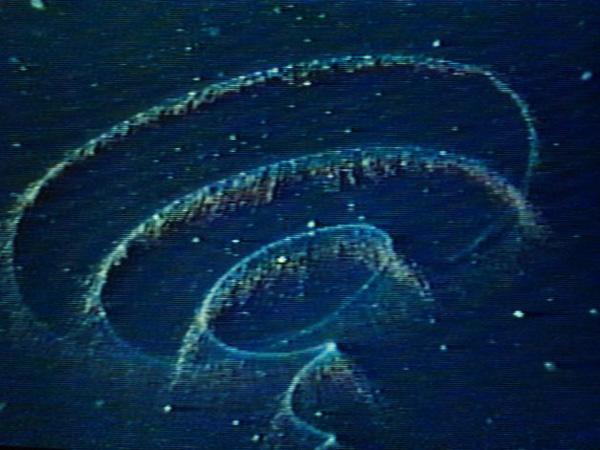

The magical lights of the deep sea.

Photo: NOAA

Fossil records suggest life here began almost one billion years ago. The fossils they find are of creatures similar and different from those inhabiting our ocean currently. As we stated that the physical planet is under constant change – life is as well. It is a system that has been working well for a very long time. Over the last few centuries humans have studied the physical and living oceans to better understand how these systems function. They have been functioning well for a very long time. And though life began at sea – there was dry land to exploit – for those who could make the trip. That will be next.

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 14, 2025

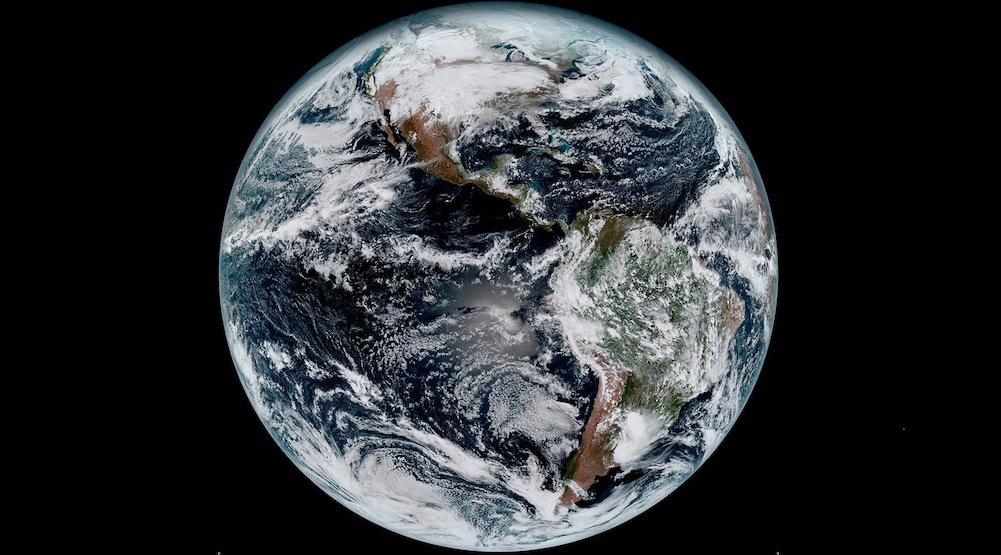

To better understand the basics of how the planet works we will use the analogy of a chicken egg. The yolk would represent the core – solid and in the middle of the planet. The mantle would be like the egg white that surrounds the yolk. It takes up most of the space, is fluid, and slowly rises and falls as it is heated by the core. The eggshell would represent the crust of the earth. Solid, and very thin. However, the crust of our planet is not smooth. It is covered with mountains and valleys, some of it above sea level but most (70%) would be below the oceans. And above the eggshell would be a thin layer of gas we call the atmosphere.

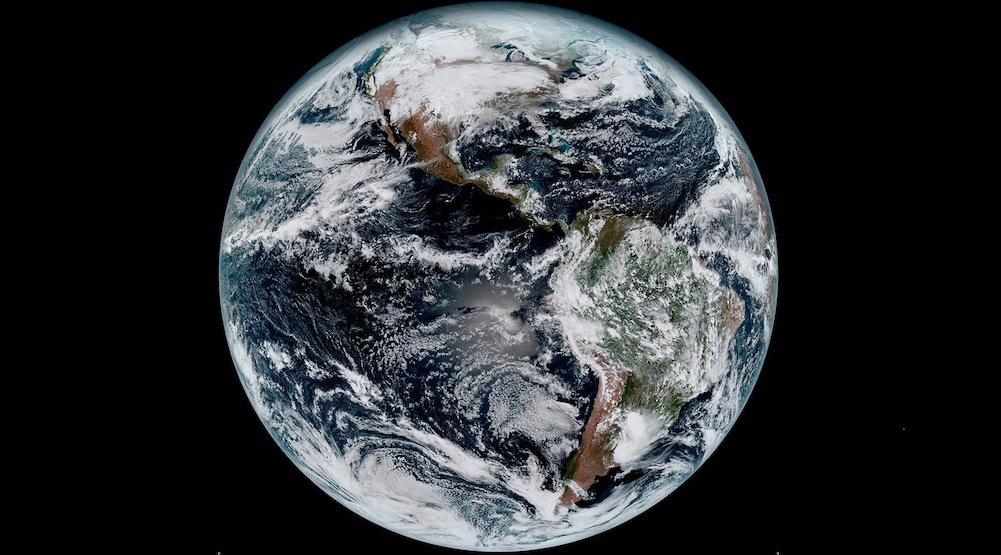

Our fragile Earth

Photo: NOAA

What we know of the core of the planet has come from seismic waves we have generated. As sound waves pass through different materials, the waves bend and reflect differently. The patterns of the refraction and reflection suggest that the core is made of iron and nickel. The temperatures here are extreme – up to 9000°F – but the intense pressure generated by gravity keeps the inner core a solid – like our egg yolk.

The mantle is actually solid rock but moves VERY slowly like a thick liquid – similar to glaciers. Like the core – the mantle is very hot but the pressure there keeps in a more solid fluid state. However, as this rock layer comes closer to the crust, the temperature is high enough, and the pressure low enough, that it becomes more fluid like – and we call it magma. This upper portion of the mantle is known by geologists as the asthenosphere.

The crust is made of solid igneous rock that is basically cooled magma. Granite is the rock that makes up the continental land masses and the denser basalt is found on the ocean floors – basalt “sinks” deeper into the more fluid mantle. Geologists call the crust the lithosphere.

The ocean is made of 97% water and 3% salt. This saltwater makes up 90% of the water on the planet. Freshwater can be found on land and in the ice of the polar regions. They refer to all of the water on the planet as the hydrosphere.

The air above the planet is a thin layer of gases made primarily of nitrogen, but also includes oxygen, carbon dioxide and other trace gases. It is called the atmosphere.

If you were to look down on the planet from the north pole it would rotate counterclockwise – from the south pole it would be clockwise. This rotation causes the hydrosphere and atmosphere to “slush around”. Add temperature and pressure change as a cause for this rotation we generate the winds and currents of our planet.

Over the last century scientists have discovered that the crust is cracked, and each section of eggshell is called a plate. These cracks provide places where molten magma can exit into the environment in the form of volcanos. These can be found on both land and at the bottom of the sea. The molten rock cools when it meets the hydrosphere and atmosphere and a cocktail of gases, liquids, and solids are produced. These gases contributed to the formation of the atmosphere that was held close to the planet by gravity.

About one billion years ago some of these molecules formed cell like structures that could take in gases, liquids, and solids and release waste products. This taking in/converting/releasing out of new materials changed the chemistry of the land, sea, and air. Oxygen increased in the atmosphere and the planet cooled to a point where these cell-like structures could live, grow, and reproduce. They produced their own energy to maintain their own metabolism and eventually some cells developed that could not make their own energy and needed to consume the cells that did – predator/prey relationships were developed.

As the planet aged and changed, the living creatures aged and changed. Many creatures could not survive the new changes and went extinct. With the new changes, new creatures would appear. Those had to deal with the conditions of either land, sea, or air and with the other creatures that lived nearby. Interactions between these creatures would change the environment and the process of change in life followed suit.

This is how our planet has functioned since its beginning. The planet changes, the living organisms change, these changes cause more changes, and the planet evolves over time. Today, there are millions of species on the planet and millions more have gone extinct. In the next article we will look at how these systems function in the hydrosphere.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 31, 2025

Each year I survey the public to determine what their needs are – what they are most concerned about – and where Extension might help. One of the primary functions of Extension is to provide local clientele with solutions to their needs – our mantra at UF IFAS Extension has been “Solutions for Your Life”. Most years the primary concern for Sea Grant locally has been water quality. Habitat restoration and invasive species also score high. These are all important issues. We want to maintain a high quality of life and addressing these concerns will help do that. And as important as these are, and they are, if someone were to ask me about my highest concern, it would be climate change. The issues above can be connected directly, or indirectly, to climate change.

Sunrise over Apalachicola Bay in Northwest Florida

Scientists have predicted, and witnessed, the negative impacts of climate change for several decades now. Nonscientists have begun to notice as well. Increased number of hurricanes, increased intensity of some of these hurricanes, excessive and extended heat waves in the summer, drought conditions in some areas of the country, flooding issues in others, and wildfires out west. These things have all happened before but in recent decades they are becoming more common.

In 2024 I wrote four articles about our changing climate in response to the devasting hurricane season we had. The reason was my concern about climate change and that we all need to pay more attention to the issue. I wrote a total of 41 articles over the course of the year – including these four on climate. The articles on climate were the least read articles of the group. There could be a couple of reasons for this. It could be that most do not consider it a high priority concern – and I understand that. Again, water quality and habitat loss are real concerns and climate maybe less so for many people. It could be that people understand the concern about climate but what can you do? It is too big of an issue for me to deal with and so, I will focus on what I can do something about. It may be because the topic is so negative – and I get this also. I taught environmental science at Pensacola State College for 15 years. Despite there being many positive lessons in the course, many students were so depressed by the final exam they would add notes such as “I will never have children” and others similar to this. Discussing the state of our environment can be a “downer”, and they just do not want to deal with it. And it could be that they deny climate change is even happening. There are many who do feel this way. In their minds, there is no issue, nothing to discuss, nothing to read about – move on.

I posted my four articles and let it ride (links to them are posted below). However, with the tragedy of the fires in Los Angeles recently, I felt it needed to be brought back up. I watched a program about the fires and a science writer, who recently published a book about climate, made a statement to the effect that “nature is letting us know that something serious is going on… nature is letting man know that we are in this together and we need to make some changes”. I agree. Though the topics of water quality and habitat loss are concerning – and Extension will provide articles and programs during the year to help the community solve those problems – I also believe that the community needs to pay more attention to climate change and enact behavior changes to solve this very serious problem.

I have decided to post articles throughout 2025 mimicking the environmental science course I used to teach. I am obviously going to shorten the subjects – and may write more in-depth articles about some of them down the road – but the outline will follow that of the course. We will begin with how the planet works. This will be followed by the introduction of humans and how we have spread across the planet. There will be articles about how we have impacted our natural resources and the climate. And we will end with some suggested methods for solving some of the problems. I am not expecting a lot of people to follow this – but I hope you will. And I hope some positive change will come from it. Let’s begin…

Climate articles from 2024

Another Look at Climate Change – Part 1 Introduction

https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/escambiaco/2024/06/20/another-look-at-climate-change-part-1-introduction/.

Another Look at Climate Change – Part 2 How Might the Earth’s Temperature and Climate Change in the Future?

https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/escambiaco/2024/06/25/another-look-at-climate-change-part-2-how-might-the-earths-temperature-and-climate-change-in-the-future/.

Another Look at Climate Change – Part 3 What are Some Possible Effects of a Warmer Atmosphere?

https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/escambiaco/2024/07/03/another-look-at-climate-change-part-3-what-are-some-possible-effects-of-a-warmer-atmosphere/.

Another Look at Climate Change – Part 4 What Can Be Done?

https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/escambiaco/2024/07/08/another-look-at-climate-change-part-4-what-can-be-done/.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 25, 2024

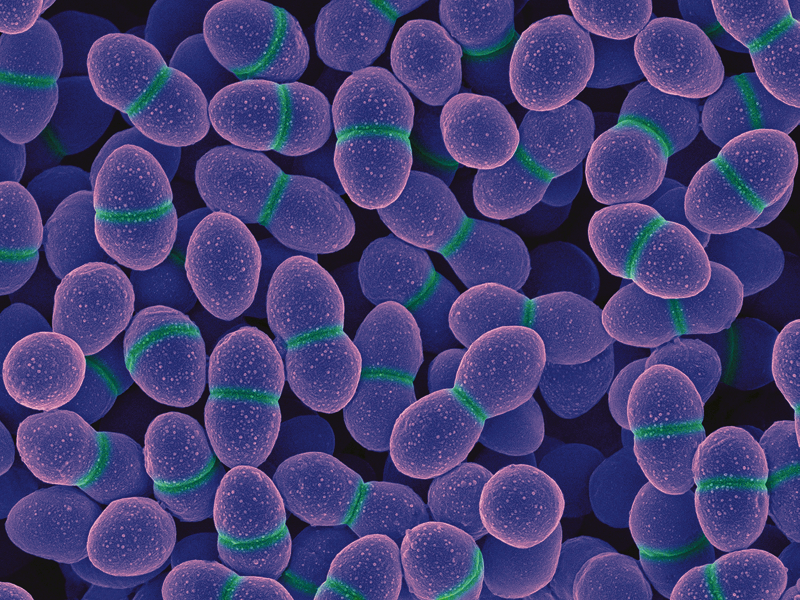

In the first article of this series, we discussed whether viruses were truly living organisms. Well, bacteria truly are. They possess all eight characteristics of life but differ from other forms of life in that they lack a true nucleus. Their genetic material just exists in the cytoplasm. This difference is large enough to place them in their own kingdom – Monera.

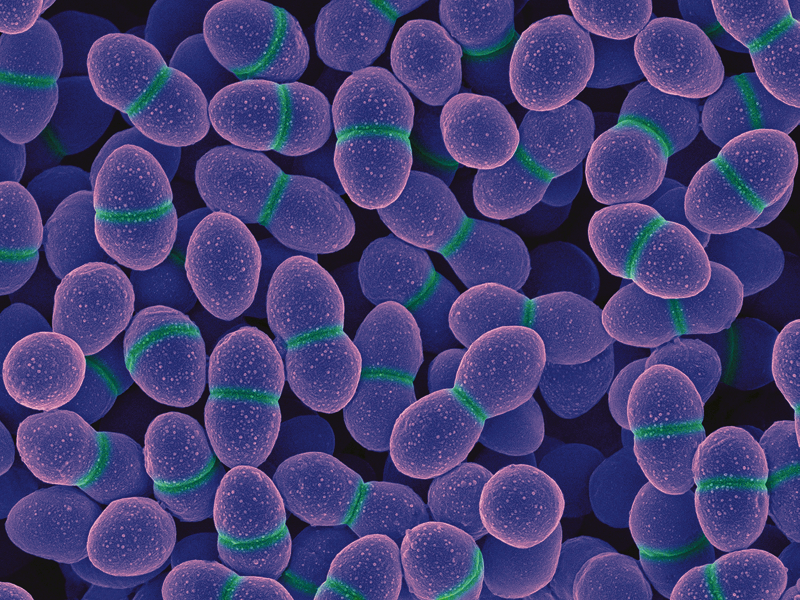

The spherical cells of the “coccus” bacteria Enterococcus.

Photo: National Institute of Health

Bacteria are single celled creatures, though some “hook” together to form long chains. A single cell will average between 5-10 microns in size. This is much larger than a virus but smaller than many eukaryotic cells (those that possess a nucleus).

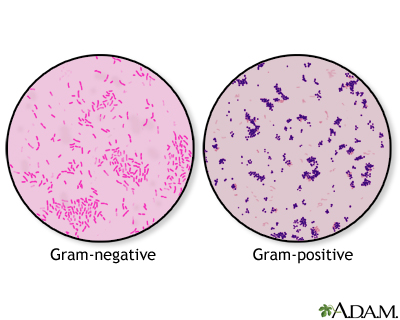

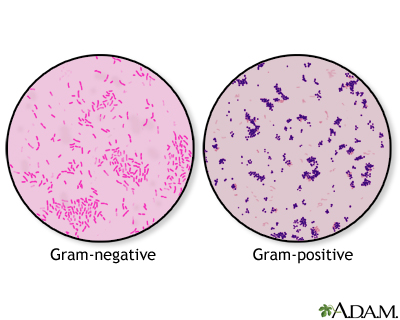

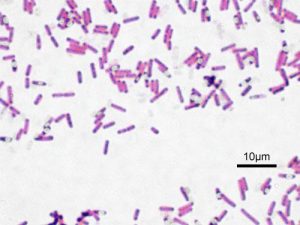

To further classify bacteria microbiologists will conduct a gram-stain test. Placing a cultured sample of bacteria on a slide, you “bath” them in what is called Gram-stain. Under the microscope the bacteria that appear “pink” are called gram negative, those that appear “purple” are gram positive. Thus, all bacteria can be quickly grouped into those that are gram negative and those that are gram positive.

After staining, gram negative bacteria appear pink in color; gram positive are purple.

Image: University of Florida

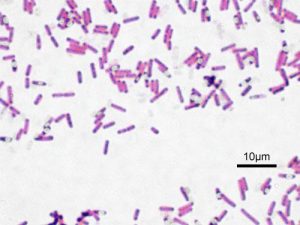

The next level of classification focuses on the shape of their cells. Those that are “rod-shaped” are called bacillus and often have the term in their name – such as Lactobacillus the bacteria found in milk that makes milk smell sour as their populations grow. The “sphere-shaped” bacteria are called coccus – such as Streptococcus (the bacterium that causes strep throat) and Enterococcus (the fecal bacterium used for monitoring water quality in marine waters). And the third group are “spiral-shaped” and are called spirillum – such as Campylobacter and Helicobacter both are human pathogens.

The rod-shaped bacterium known as bacillus.

Image: Wikipedia.

The bacterium known as coccus.

Image: Loyola University

The bacterium known as spirillum.

Image: Lake Superior College.

Bacteria are very abundant in the marine and estuarine waters of the Gulf of Mexico. They can be found floating in the water column, on the surface of the sediment, beneath the surface of the sediment, and on the bodies of marine organisms. When we think of bacteria we think of “dirty” conditions and disease, but many bacteria provide very important ecological benefits to the marine ecosystem and are “good” members of the community.

One important role some bacteria play is the conversion (“fixing”) of nutrients. Animals release toxic waste when they defecate and urinate. One of these is ammonia. Ammonia can bond with oxygen depleting the body of this needed element. Nitrogen fixing bacteria can convert toxic ammonia released into the environment into nitrite. Then another group of nitrogen fixing bacteria will convert nitrite into nitrate – a needed nutrient for plants, and eventually the entire food chain.

Some bacteria are excellent decomposers. When plants and animals die we say they “decay”. What is actually happening is the decomposing bacteria are converting nutrients in their bodies to forms that are usable by living organisms. One byproduct of this decomposition process is hydrogen sulfide – which smells like rotten eggs. In biologically productive ecosystems – like swamps and marshes – the smell of hydrogen sulfide is strong – often called “swamp gas”. It is the smell of nutrient conversion and much needed. Though in high concentrations, hydrogen sulfide is toxic as well – there needs to be a balance. We see this same process happenings when we compost food waste to form fertilizers for our gardens.

One place where the smell of sulfur is very strong is near volcanic vents. If you have been to Yellowstone, or a volcano, the smell is very evident. There are what are termed “extreme bacteria” who can live in these very hot, almost toxic, environments. Just as plants take water and carbon dioxide and convert this to sugar in the process of photosynthesis, bacteria can convert toxic forms of sulfur into usable carbohydrates for other living organisms. In the 1970s marine scientists discovered thermal vents on the bottom of the ocean. These hot “chimneys” spew black clouds of smoke into the water column. Approaching these chimneys carefully they found water temperatures between 700-800°F! Living close to these chimneys they found communities of worms, shrimps, fish, and crabs. The walls of the chimneys are actually composed of sulfur fixing bacteria that are converting volcanic minerals and compounds into sugars in a process called chemosynthesis – which supports these deep-sea communities.

The black smokers – hydrothermal vents – found on the ocean floor.

Photo: Woodshole Oceanographic Institute.

Of course, there are more familiar forms of bacteria that cause disease. Called pathogens – they can be problems for all marine life and sometimes humans. Fecal bacteria associated with human waste are not toxic in themselves at low concentrations. However, if their numbers increase (due to a sewage spill, etc.) these, and other possible pathogenic human bacteria, can be a human health issue. The Florida Department of Health monitors the fecal bacteria levels weekly at beaches where humans like to swim. High concentrations will require the department to issue health advisories. We know that all sorts of bacteria begin to replicate quickly in warmer conditions. This can be a problem with seafood that is not kept cold enough before serving. There are federal regulations on what temperatures commercially harvested seafood must be kept in order to be served or sold to the public. Federal and state agencies can monitor the temperatures of stored seafood as it moves from the fishing vessel to the table. But they cannot monitor it from your fishing rod to your table – that responsibility will fall on you. Pathogenic bacteria is the primary reason we refrigerate and/or freeze much of our food.

Closed due to bacteria.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Though bacteria in general have a bad name, many species are not harmful to us and are a major player in the health of our estuarine and marine communities.

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 4, 2024

Coastal wetlands are some of the most ecologically productive environments on Earth. They support diverse plant and animal species, provide essential ecosystem services such as stormwater filtration, and act as buffers against storms. As Helene showed the Big Bend area, storm surge is devastating to these delicate ecosystems.

Hurricane Track on Wednesday evening.

As the force of rushing water erodes soil, uproots vegetation, and reshapes the landscape, critical habitats for wildlife, in and out of the water, is lost, sometimes, forever. Saltwater is forced into the freshwater wetlands. Many plants and aquatic animal species are not adapted to high salinity, and will die off. The ecosystem’s species composition can completely change in just a few short hours.

Prolonged storm surge can overwhelm even the very salt tolerant species. While wetlands are naturally adept at absorbing excess water, the salinity concentration change can lead to complete changes in soil chemistry, sediment build-up, and water oxygen levels. The biodiversity of plant and animal species will change in favor of marine species, versus freshwater species.

Coastal communities impacted by a hurricane change the view of the landscape for months, or even, years. Construction can replace many of the structures lost. Rebuilding wetlands can take hundreds of years. In the meantime, these developments remain even more vulnerable to the effects of the next storm. Apalachicola and Cedar Key are examples of the impacts of storm surge on coastal wetlands. Helene will do even more damage.

Many of the coastal cities in the Big Bend have been implementing mitigation strategies to reduce the damage. Extension agents throughout the area have utilized integrated approaches that combine natural and engineered solutions. Green Stormwater Infrastructure techniques and Living Shorelines are just two approaches being taken.

So, as we all wish them a speedy recovery, take some time to educate yourself on what could be done in all of our Panhandle coastal communities to protect our fragile wetland ecosystems. For more information go to:

https://ffl.ifas.ufl.edu/media/fflifasufledu/docs/gsi-documents/GSI-Maintenance-Manual.pdf

https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/news/2023/11/29/cedar-key-living-shorelines/