by Rick O'Connor | Jun 23, 2022

“Bluefish!” … “It’s just a school of bluefish!” So yelled the lifeguard in Jaws II when Chief Brody had mistaken a school of bluefish for the rogue great white shark that was plaguing the town. He would not have been the first to mistake these large schools for a larger fish, particularly a predatory shark, but as some know, bluefish are quite predatory themselves.

Bluefish

Image: University of South Florida

Growing up along the Florida panhandle we heard little about this species. We had heard stories of large bluefish schooling along the Atlantic coast killing prey with their razor-sharp teeth and, at times, biting humans. But not much was mentioned about them swimming along our shores. But they do, and I have caught some.

Bluefish are one of several in a group Hoese and Moore refer to as “mackerel-like fish” in Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico. They differ in that they lack the finlets found along the dorsal and ventral sides of the mackerel body and mackerels lack scales having a smoother skin. Bluefish are the only members of the family Pomatomidae. They can reach three feet in length and up to 30 pounds. They travel in large schools viciously feeding on just about anything they can catch and seem to really like menhaden. They move inshore for feeding and protection from larger ocean predators but do move offshore for breeding.

Bluefish landed from the Gulf of Mexico are much smaller than their Atlantic cousins, rarely weighing in more than three pounds. They do have a deep blue-green color to them and thin caudal peduncle and forked tail giving them the resemblance of a mackerel or jack. Some say they are bit too oily to eat while others enjoy them quite a bit. There is a commercial fishery for them in Florida and, as you would expect, it is a larger fishery along the east coast. Most of the panhandle counties have had commercial landings, albeit small ones.

Biogeographically, the blue fish are found all along the Atlantic seaboard and into the Gulf of Mexico. It is listed as worldwide but seems to be absent from the Caribbean and other tropical seas. This could be due to a distaste of warmer waters, or the lack of their prey targets.

They are an interesting and less known fish in our region. Swimming in a school of them should be done with caution, there are reports of nips and bites from these voracious predators.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 29, 2022

I recently saw a news clip about a new Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation (FWC) ruling for shrimpers. I was interested in this new ruling but also asked the question – “Where did all of the shrimpers go?”

What I mean by this is that when I was young there were shrimp boats on Pensacola Bay every evening. They seemed to trawl one side of the Pensacola Bay Bridge or the other, but you could see the lights on the decks of each trawler and there were many, looking like front porch lights of a small community, all over the bay. In the morning they would head towards the seawall along both sides of Palafox Street near the old Pensacola Municipal Auditorium and sell from the boats. We made frequent trips there.

Then the boats stopped coming to the docks…

And the Municipal Auditorium is now gone also…

Shrimping in the Gulf of Mexico.

Photo: NOAA

The focus turned to the docks near Joe Patti’s. Joe Patti’s, American, and Allen Williams Seafood companies were places we would frequent to purchase shrimp when they came in. Then those slowly disappeared with only Joe Patti’s remaining open to the public. The shrimp boats still come to the docks of Allen Williams, but in fewer numbers and the shrimp began to go through Joe Patti’s, Maria’s, Perdido and other seafood markets. Now the lights on the bay at night are few. Actually, I rarely see them anymore. Where did they go?

As you look at the commercial landings of shrimp since 1980 you see some interesting trends.

First, understand that commercial landings mean this is where the shrimpers “land” their catch, not where they caught it.

Second, that brown shrimp (bay shrimp) are BY FAR the most landed species in Escambia County. Comparing brown shrimp to white (also called Gulf shrimp), rock shrimp, and royal reds, there was a total of 13,372,791 lbs. of brown shrimp landed between 1984 and 2019. For the others white shrimp was 255,587 lbs., royal reds 95,920 lbs., and rock shrimp 78,817 lbs. You could also say the same for effort. Between 1984-2019 there were 31,935 trips for brown shrimp, 904 for white shrimp, 143 for rock shrimp, and only 19 for royal reds. So, brown shrimp are king for commercial landings here.

Third, there were 1000 or more trips per year for brown shrimp until 2002. That year it dropped to 835. In 2003 that was cut in half to 453 and the trend continued to decline. Between 2017-2019 there were less than 100 trips each year. There is a similar pattern for white shrimp. Prior to 2002 the number of trips for white shrimp were in the double digits, occasionally in the triple, each year. In 2002 it dropped from 38 to 7 per year and never recovered. Though royal reds and rock shrimp were never big players in local landings, between 2010 and 2019 there was only one trip for rock shrimp and no trips were logged for royal reds. What happened?

The famous Gulf Coast shrimp.

Photo: Mississippi State University

To try and find answers I reached out to a couple of my seafood contacts. Teresa and Bob Pitts are from the Perdido Key area and have been involved with commercial fishing most of their lives. Teresa currently manages Perdido Seafood and Bob works with the National Park Service but they both have strong ties to this industry. Jimbo Meador is a lifelong resident of Mobile Bay and has been involved in several industries including seafood over there. Jimbo recently retired from being nature tour operator in the Mobile Delta but still has ties to the seafood business and a wealth of knowledge. Dr. Andrew Ropicki is an economist with Florida Sea Grant and the University of Florida who focuses on seafood and other marine related topics. I had a conversation with all, and comments were made that helped connect some the dots.

In 1995 the state imposed a net ban on all entanglement nets 500 ft2 or larger from state waters. This obviously would have included Pensacola Bay. I know the shrimpers were opposed to this amendment. They were very visible and vocal about it. Once passed it would make sense they would move their operations from Pensacola Bay to Alabama, or federal waters offshore, so they could continue to use their standard sized otter trawls. Honestly, I do not remember which year the deck lights of the shrimp boats began to disappear, but I would guess many did leave when this law was passed. However, this did not impact the number of landings, they continued to bring shrimp here.

Otter trawl is correct name for what folks call a shrimp net. In 1995 any entanglement net over 500 square feet were banned in Florida waters.

Prior to 1995 landings of brown shrimp ranged from 1114 to 2523 a year with an average of 1760. Between 1995 and 2000 the range was from 1134 to 1816 with an average of 1442. A slight drop, but nothing significant. If they were shrimping somewhere else, they were still landing in Escambia County. I recently had a conversation about this with Bob Jackson, one of my citizen science volunteers. He moved here around 2000 and remembered shrimp boats still being on the bay at that time. Some may have moved due to the net ban, but not all. The shrimping was still on.

In 2002 the landings did take a significant drop – 835 landings that year. The first time they were below 1000/year since the records were kept in 1984. In 2003 they dropped further to 453 and the decline has continued ever since. Where were they landing their shrimp? Were they still shrimping? I do not know.

Jimbo asked the question “when did the surge of foreign imports begin?” Good question. We know now that at least 80% of the seafood consumed in Florida is imported. When did this move from local to import make this big swing? Dr. Ropicki found a world shrimp production graph that showed 2003 as a year with a big increase in aquaculture shrimp. Aquaculture accounted for 28% of global shrimp production in 2000 and 55% in 2010, and that is with wild caught shrimp increasing slightly. The big swing towards aquaculture in 2003 closely mirrors the decline in local wild harvest landings in 2002. This certainly could be a piece of the puzzle.

Seafood markets offer local products as well as those from around the world.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

Did this competition with imports create less effort on the part of local shrimpers?

It certainly had some impact. All of my contacts indicated that the price difference between imported and local seafood made it much more difficult to do business. Add to this the rise in cost of fuel, insurance, and regulations to the industry, some captains did sell their boats and found another line of work.

Looking at the fuel story, Dr. Ropicki found a chart published by the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The chart shows how Gulf coast #2 diesel prices have changed since 1995. Basically from 1995 to 2021 they tripled (200% increase) while general inflation was only about a 75% increase. As many know it is a very fuel intensive industry.

In 2004 Hurricane Ivan hit our area and that certainly would have caused a decline in landings due to damage to boats and docks. The number of landings that year was 388. Between 2004 and 2010 landings steadily declined from 388 to 155/year. The days of 1000+ landings seemed to be over. Many shrimpers lost their boats during the storm and just found another line of work.

Hurricanes are one reason some shrimpers have left the business.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

To add fuel to the fire, in 2010 the Deepwater Horizon oil spill occurred. That year there were only 85 landings in Escambia County, the first year we had less than 100. But we understand why – no shrimping occurred with oil in the water. Many shrimpers still in the business were hired to help clean up the spill, and did make money doing it, but they were not landing shrimp.

The BP Oil Spill was one of the worst natural disasters in our country’s history.

Photo: Gulf Sea Grant

In 2011 landings returned to 187 for the year and even up to 235 in 2012, but since there has been again a steady decline. In 2017 we went below 100 landings again. Between 2017 and 2019 the landings in Escambia County were 66, 53, and 70 respectively – the lowest ever. FAR below the 1000-2000 landings in the 1980s and 1990s.

Further discussion with my contacts yielded another trend. Commercial fishing historically was a family venture. Families worked the boats and sons took over the business from their fathers. That seems to have stopped. One shrimper who did talk to me said at one point we had between 40-50 boats in our fleet, now there are 11 and their kids want nothing to do with the business. As one of the contacts mentioned “they would rather work with their brains than their backs”.

Commercial seafood in Pensacola has a long history.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

In Alabama many families actually lived on their boats and the entire family would go out when the shrimping was on. I was told they do not see this anymore. There are still some bay shrimpers who sell their catch along the Hwy 90 causeway crossing Mobile Bay, and they seem to be doing well, but there are fewer of them. I was also told that many of the Gulf shrimp boats in Alabama have been sitting idle at dock for several years, many are up for sale, and it has been primarily foreign businesses buying them. There were once 120 Gulf shrimp boats in the fleet at Bon Secour Seafood, now there is one. I recently heard a Pensacola shrimper who made port in Bayou Chico – just sold his boat this year.

Dr. Ropicki also shared data on price for shrimp. Could this play a role in this story?

Most commercial seafood products have seen an increase in purchase price at the dock, but not shrimp. Checking the state records for price/pound for brown shrimp in Escambia County found some interesting trends. Between 1985 and 2020 the average price paid for their harvest was between $1.50 and $2.00 a pound. At least once each decade the price went to $2.00 or more per pound – but only ONCE each decade. In that time the number of years where the price dropped BELOW $1.50 per year steadily increased. Between 1985-89 the price dropped below $1.50 only once. Between 1990-1999 it never dropped below. Between 2000-2009 it dropped below $1.50/lb. six times. This happened again between 2010-2019 – six times. In 2006 local shrimpers only got $1.01/pound for the work – the lowest in this data set. If you look at the average price a shrimper received for their brown shrimp harvest by decade you see…

1985-89 – $1.82

1990-1999 – $1.78

2000-2009 – $1.58

2010-2019 – $1.54

A steady decline over time. Along with storms, regulations, fuel costs, lack of labor, and competition with imports, you can add price to the “soup of problems”.

I was curious if a similar scenario was playing out in Apalachicola. Apalach is known for their oysters, but there is a sizable shrimping industry there as well – it’s a seafood town. I asked our Sea Grant Agent over there, Erik Lovestrand, about similar trends. He did not have any data but was reasonably certain that the number of boats working out of their docks had significantly declined over the years.

Known for their oysters, Apalachicola is also a shrimping town.

I decided to take a look at the landing numbers for Apalachicola. I looked at brown shrimp.

Between 1985-1989 they averaged 909 landings – less effort for this species than in Escambia County.

Between 1990-1999 there averaged 1546 landings a year.

Between 2000-2009 the average was 382.

And between 2010-2020 it was 68.

The pattern looks similar albeit the number of landings was brown shrimp were less in Apalachicola. However, I did see another interesting difference – price paid per pound. In Escambia over this time the average price was $1.66/pound. It only went to $2.00/pound once decade and began to drop below $1.50 frequently over the last 20 years. However, in Apalachicola the average price was $2.00 rarely going below that and even reached $3.32/pound in 2014. They pay more for brown shrimp in Apalach. I am not sure if that impacted landings locally. The data suggests that it did not, but it is interesting.

And then, another thought came to mind. From the Big Bend of Florida south to Key West pink shrimp, not browns, are the target species. What did the pink shrimp landings look like? Did Escambia make a switch?

The results were interesting. Between 1985-2021 the landings of pink shrimp in Apalachicola occurred every year. The total number of landings was 6431 and averaged 174/year. The price was good, ranging from $1.80 to $3.23/pound, the average price was $2.39. The number of trips per year never broke 500 and the trend on landings shows a decline over this time period. But the price was decent for those who chose to target this shrimp.

In Escambia County the effort was low. They did not continuously land pink shrimp each year, but rather over short periods. Landings occurred between 1986-1991. Then nothing until 1997. Then another short period from 2000-2003. Then nothing again until 2014, which ran until 2020. Other than in 2000, the number of trips for pink shrimp were less than 10 a year (they were 10 in 2000). The average number of trips since 1986 was 4/year – less than Apalachicola and much less that the brown shrimp harvest here.

However, the price per pound was much higher for pink shrimp in Escambia. It ran from $1.59 to $5.00/pound! The average price was $2.77 (more than what they were paying in Apalachicola). Though Escambia landings were not big for pink shrimp, it was certainly more profitable than brown shrimp.

Pink shrimp are very popular.

All of the above played play a role in the decline of the local shrimping industry. However, if you visit a local seafood market you will find shrimp. Some is still local, local landings may be down, but they have not stopped. Some are local in the since they were harvested elsewhere in the Gulf of Mexico and trucked to us. But as we mentioned, cheaper imports are easier to get. So, it does not seem we are going to run out of shrimp, just out of shrimpers. For some it is unnerving that we will be dependent on other countries for our seafood, but we will have seafood.

Which brings up the topic of aquaculture. This is for another article. Until then, we do encourage you to enjoy seafood, it is a healthy source of protein. We will see where the local industry heads in the next decade, but you can still get shrimp, and I have seen nice looking ones in there. Enjoy them.

A rare site – a shrimping landing its catch in Pensacola Bay in 2022.

Note: After completing this article I had a meeting in Bayou LaBatre AL. I was told that shrimping industry there was hanging on… barely. Also, the high school teacher I met with said he was not aware of one kid in the school who planned to become a shrimper… this is in Bayou LaBatre Alabama.

Special thanks to

Bob and Teresa Pitts – Perdido Bay Seafood

Jimbo Meador

Dr. Andrew Ropicki – University of Florida / Florida Sea Grant

Erik Lovestrand – UF IFAS Extension / Florida Sea Grant / Franklin County

Bob Jackson

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 24, 2022

I am going to be honest and say that I know very little about this fish. I did not know they even existed until I attended college. Shortly afterwards, my father-in-law asked “hey, have you ever heard of a tilefish?” – to which I responded yes… He was having lunch at a restaurant in Apalachicola, and it was on the menu. My father-in-law was an avid fisherman and knew most of the edible species, but he had not heard of this one. The rumor was that it was pretty good, though my father-in-law chose not to eat it that day.

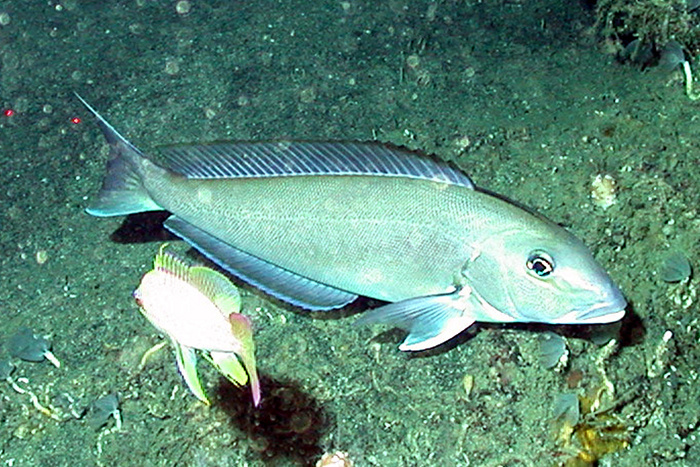

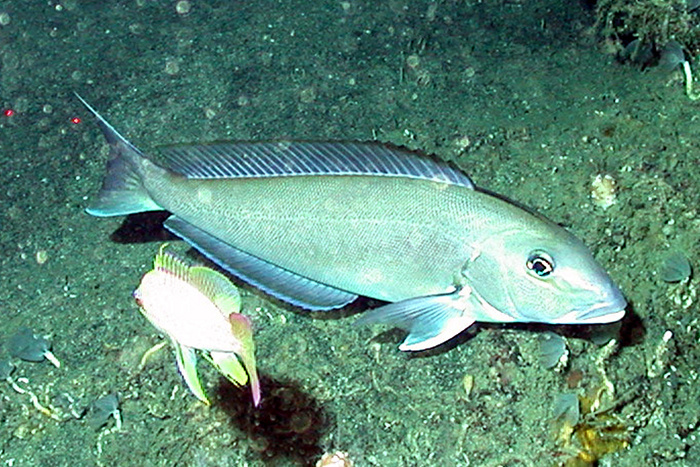

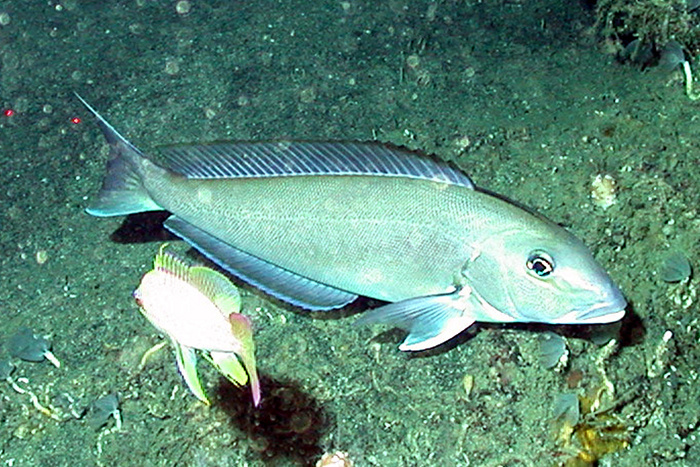

Tilefish

Photo: NOAA

I have never seen it on a menu, and only a few times in the local seafood markets, but according to Hoese and Moore1 by the late 1970s there was a small commercial fishery for this fish emerging in Louisiana, as was a small recreational fishery. In Florida, since 2000, there have been 15,435 commercial trips for this fish with an average of 321 each year. The value of this fishery over that time is $33,118,554 with an average of $689,969.90 each year. The average price for the fishermen was $2.62 per pound with the highest being $5.14/lb. on the east coast and that in 2022; the Gulf fishermen are getting $4.16/lb. right now.

The highest number of landings per county since 2000 was 340 in Palm Beach County in 2000. Only eight times has there been more than 200 landings in a single year over the last 22 years. Five of those were in Monroe County (Florida Keys) and three were again in Palm Beach County. The vast majority were less than 100 landings in a single year, this is not a large fishery in Florida either.

Are they harvested here in the Florida panhandle?

Yes… Bay, Escambia, Franklin, Okaloosa, Wakulla, and Gulf Counties all reported landings. Bay County seems to be the hot spot for panhandle with landings between 50-100 each year since 2000. Most of the other counties report less than 10 a year and several only reported one. Again, this is not a large fishery, but it was sold at a restaurant in Apalachicola and is said to be good. Hence, I decided to include in this series.

Hoese and Moore report four species of tilefish in the Gulf of Mexico. The sand tilefish (Malacanthus plumeri) is a more tropical species. The tilefish (Lopholatilus cheamaeleonticeps) and the gray tilefish (Caulalatilus microps) seem to be the target ones for fishermen. Both are reported from deep cold water near the edge of the continental shelf. FWC reports them from 250 – 1500 feet of water where the temperatures are between 50 – 60°F. Because of their tolerance to cold water, their geographic range is quite large; extending across the Gulf, up the east coast to Labrador. They live in burrows on hard sandy bottoms and feed on crustaceans. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration2 reports this as a slow growing – long lived fish, up to 50 years of age. In their cold environment, this makes sense.

This is not a well-known fish along the Florida Panhandle but maybe one day you will see it on the menu, remember this article, and take a chance to see if you like it.

References

1 Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station TX. Pp. 327.

2 Golden Tilefish. 2020. Species Directory. NOAA Fisheries. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/golden-tilefish.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 11, 2022

Let’s begin by stating what a diamondback terrapin is. I have found many Floridians are not familiar with the animal. It is a turtle. A turtle in the family Emydidae which includes the pond turtles, such as cooters and sliders. The big difference between terrapins and the other emydid turtles is their preference for salt water. They are not marine turtles but rather estuarine – they like brackish water.

The diamond in the marsh. The diamondback terrapin.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Their haunt are the salt marshes and mangroves of the state. Their range extends from Massachusetts down the east coast and covering all of the Gulf of Mexico over to Brownsville Texas. There are seven subspecies of the animal within that range. Five of those live in Florida and three only live in Florida. They are more abundant, and well known, in the Chesapeake Bay area where they are the mascot of the University of Maryland. In Florida they seem to be more secretive and hidden. Encounters with them are rare and there has been concern about their status for years. Though researchers are not 100% sure on their population size, it was felt that more conservation measures were needed.

Ten years ago, the issue with all turtles in the state was the illegal harvest for the food trade. All sorts of species were being captured and sent to markets overseas. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) stepped in and set possession quotas on many species of Florida turtles. For terrapins, the number was two. For some, like the Suwannee Cooter, there was a no possession rule.

Drowned terrapins in a derelict crab trap in the Florida panhandle. (photo: Molly O’Connor)

There has also been concern with incidental capture of terrapins in crab traps. These turtles have been known to swim into the traps and drown. In the Chesapeake Bay area, they have found as many as 40 dead turtles in one trap. Not only is this bad for the turtles, but it is also bad for the crab fisherman because high numbers of dead turtles in the trap means no crabs. Studies began to develop some sort of excluder device that would keep terrapins out, but allow crabs in. Dr. Roger Wood developed a rectangle shaped wire excluder now called a By-Catch Reduction Device (BRD) that reduced the terrapin capture by 80-90% but had no significant effect on the crab catch. That was what they were looking for. This BRD has been required on crab traps up there for years.

What about Florida?

Studies using the BRD were also conducted here with the same results, but the BRD was not required. Incidental capture in crab traps does occur here but not to the extent it was happening in the Chesapeake and FWC wanted to hold off for more science before enacting the rule. BRDs were available for those who wanted them, but not required. This past December (2021) that changed.

This orange plastic rectangle is a Bycatch Reduction Device (BRD) used to keep terrapins out of crab traps – but not crabs.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

In recent years there has been another issue with harvesting terrapins for the pet trade. With this, and other conservation concerns for this turtle, FWC developed a new rule for terrapins at their December 2021 meeting.

- The possession limit for terrapins has dropped from 2 to 0 – there is a no-take rule for this animal beginning March 1, 2022. Collection for scientific research will still be allowed with a valid collecting permit from the FWC. Those who currently have two or less terrapins in their possession as pets may keep them but must obtain a no cost personal possession permit to do so by May 31, 2022. Those who have terrapins within an education center may keep them but must obtain a no cost exhibit permit by May 31, 2022.

- Recreational crab traps will require the BRD device by March 1, 2023. You have a year. Those in the Pensacola area can contact me for these. I have a case of them I am willing to provide to the public.

Again, studies have shown that these BRDs do not significantly impact the crab catch. Crabs can turn sideways and still enter the traps. But reducing incidental capture of terrapins will hopefully increase their numbers in our state. For information on how to obtain the needed permits visit FWC.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 23, 2021

These are all fish that many have heard of but know nothing about. They are not even sure what they look like. We have heard of them as a seafood product. Smoked herring, canned sardines, and anchovy pizza are popular the world over. These are one of the largest commercial species harvested in U.S. waters. In 2020 over 6 million pounds of sardines, 12 million pounds of anchovies, 41 million pounds of herring, 1.3 BILLION pounds of menhaden were harvested. The menhaden catch alone was valued at just under $200 million2. It not as large a fishery in Florida. 327,000 pounds of menhaden, 700,000 pounds of sardines, and 1.8 million pounds of herring were harvested from state waters in 2020 and at value of about $900,000 in 2020. The fish are popular in many European dishes, cat food, and menhaden oil is used in many products.

The Gulf menhaden supports a large commercial fishery in the Gulf of Mexico.

Photo: NOAA

These fishes are actually divided into two families. The herring, sardine, and menhaden are in the Family Clupeidae and are often called “clupeids”. This family includes 11 species in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Most have a “hatchet” shape to their bodies – being straight along their back with a deep curve along the ventral side, and most having a forked, or lunate, tail. They average between 2-20 inches in length and form massive schools as they travel near the surface waters filtering plankton. They are often harvested using purse seines. Large factory vessels will plow the waters searching for the large schools. Often, they will use aerial assistance to search such as small airplanes or ultralights. Once spotted, small chase boats will be launched from the factory vessel hauling the large purse seine around the school. Once that is completed a large weight called a “tommy” is dropped that “zips” the purse shut and captures the fish. There is little bycatch in this method.

Purse seining in the Pacific Ocean.

Photo: NOAA

The anchovies are found in the family Engraulidae. They differ in that they are more streamlined in shape and their mouths are larger / body size than the clupeids. Though there is no commercial fishery for them in Florida, they comprise one of the largest groups of schooling fish in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Hoese and Moore mention that the local species are too small for a fishery. The five native species average between 2.5-5.5 inches in length1. Some marine biologists consider anchovies as an “environmental canary”, or indicator species. Their presence can suggest good water quality. I have often caught them in seines along the beach in the Pensacola area. They resemble the very common silverside minnow in that they have a silver stripe running down their sides. But they differ in that they (a) only have a single dorsal fin (silversides have two), and (b) their snouts extend to a point resembling the head of a shark.

This striped anchovy resembles a silver side but differs with the shape of its snout and the number of dorsal fins.

Photo: NOAA

The distribution and biogeography of this group of fishes is all over the place. The round herring (Etrumeus teres) has few barriers and is found from the Bay of Fundy (at the Canadian/Maine border) to the Pacific Ocean1! A few species have the classic “Carolina” distribution – meaning they are found from North Carolina south, the entire Gulf of Mexico, and down to Brazil. For whatever reason (currents, water temperature, other) they do not venture north of the Carolinas and are probably impacted by the large amount of freshwater entering the Atlantic Ocean near the Amazon River.

Twp species are restricted by tropical conditions. The tiny dwarf herring (Jenkinsia lamprotaenia) and the Spanish sardine (Sardinella anchovia) are both listed as being restricted by water temperatures, though I have captured plenty of the Spanish sardines in the Pensacola area.

Some species are restricted to either the eastern or western Gulf of Mexico. Usually, the barrier for this distribution is the Mississippi River. Like the Amazon, there is a large plume of highly turbid/low salinity water extending into the Gulf of Mexico which keeps some species from crossing. Hoese and Moore report the Alabama shad (Alosa alabamae) only from the area between the Mississippi River and the Florida panhandle. The Mississippi River to one side, and the Apalachicola on the other.

Clupeids, like this Pacific sardine, for m large schools can consist of literally millions of fish.

Photo: NOAA

And finally, there is a spatial distribution with some species between freshwater, estuaries, and the open shelf. Two species, the threadfin shad (Dorosoma petenense) and the gizzard shad (Dorosoma cepedianum) are more associated with freshwater. The scaled sardine (Harengula pensacolae) is more common on the open shelf of the Gulf.

We all know the names of these fish but are unaware of their general biology and importance to commercial fisheries around the world. Many are common in our estuaries and play an important role in the health of the overall ecology. They are important members of the “panhandle fish family”.

References

1 Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

2 NOAA Fisheries. 2021. Commercial Landings. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/foss/f?p=215:200:2082956461436::NO:::.

3 Florida Commercial Landings. 2021. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. https://myfwc.com/research/saltwater/fishstats/commercial-fisheries/landings-in-florida/.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 27, 2021

For those who lived in the Pensacola Bay area 50 or so years ago, this question comes up from time to time. By scallop I am speaking of the bay scallop (Argopecten irradians), the one sought by so many scallopers then and now. This relatively small bivalve sits on beds of turtle grass, gazing with their ice blue eyes, filtering the water for plankton and avoiding numerous predators. They only live for a year, maybe two. They aggregate in relatively large groups and mass spawn. Releasing male gametes first, then female, fertilizing externally in the water column, to create the next generation.

Bay Scallop Argopecten iradians

http://myfwc.com/fishing/saltwater/recreational/bay-scallops/

These are unique bivalves in that they can swim… sort of. When conditions are not good, or a predator is detected, they can use their single adductor muscle to open and close the shells creating a current of expelling water that “pushes” them along and off the bottom. They were once found from Pensacola to Miami… but no longer. Scallops have become almost nondetectable in much of their historic range. Today they congregate in the Big Bend area of the state, and there they are heavily harvested.

What happened?

Well, if you look at the variety of causes for species decline around the globe habitat loss is usually at the top of the list. The habitat of the bay scallop are seagrass beds. There are many publications reporting the loss of seagrasses across the Gulf and Atlantic coast. Locally we know that the historic beds of the Pensacola Bay system have declined. We also know that some of those beds have shown some recovery in the last 20 years. But was the loss enough to cause the decline of the scallop?

Studies show that there is a strong association between seagrasses and scallops. The planktonic larva typically attached to grass blades a week or two after fertilization. This seems essential to reduce predation. Once they drop from the blades, vegetative cover is important for their survival. This suggests yes – any loss of seagrass could begin the loss of bay scallops.

What about water quality?

We do know that scallops need more saline brackish water – at (or above) 20 parts per thousand (20‰); 10‰ or less is lethal. Sea Grant is currently working with citizen scientists in Escambia County to monitor the salinity of area waters weekly. Though we do not believe the data is usable until we have 100 readings from each location, early numbers suggest that locations in Big Lagoon and Santa Rosa Sound are at 20‰ threshold. We do not know whether run-off engineering of the 1970s may have lowered the salinity to cause a die-off, and one would think (since they can swim) they would move to a better location. However, if salinities were low across much of their local range, and seagrasses were not available in areas where salinities were good, this could have a devasting impact on their numbers.

Then there is sedimentation. Studies show that young scallops (<20mm) that do not have seagrass to attach to settle on silty bottoms and their survival is very low. And then there are toxic metals, and other contaminants that scallops may have little tolerance for. It is known that juvenile scallops have a low tolerance for mercury.

Disease?

One study from the Tampa Bay area indicated that there was little loss of scallops due to disease and parasites.

And then there is overharvesting…

Scallops are mass spawners and there needs to be high numbers of adults near each other for reproduction to be successful. If people are taking too many, this can lead to more spaced adults and less chance of successful fertilization. This combined with environmental stressors probably did our populations in.

According to a publication from Sarasota Bay Estuary Program in 2010, populations of less than five scallops / 600m2 is considered collapsed. Sea Grant has been conducting volunteer scallop searches in the Pensacola Bay area for the last five years. In that time, we have found only one live scallop… we have collapsed. During the 2021 Scallop Search, 17 volunteers surveyed 4000m2 and found no live scallops. However, reports of live scallops outside of our surveys indicate they are still there. We will see what the future holds.

References

Castagna, Michael, Culture of the Bay Scallop, Argopecten irradians, in Virginia (1975). Marine Fisheries

Review, 37(1), 19-24.

https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles/1200

Leverone, J.R. 1993. Environmental Requirements Assessment of the Bay Scallop

Argopecten Irradians Concentricus. Final Report. Tampa Bay Estuary Program. Pp.82.

Leverone, J.R., S.P. Geiger, S.P. Stephenson, and W.S. Arnold. 2010. Increase in Bay Scallop (Argopecten irradians) Populations Following Releases of Competent Larvae in Two West Florida Estuaries. Journal of Shellfish Research. Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 395-406.