by Rick O'Connor | Jun 26, 2020

This is a good name for this group. They are mollusk that have two shells. They tried “univalve” with the snails and slugs, but that never caught on – gastropods it is for them. The bivalves are an interesting, and successful, group. They have taken the shell for protection idea to the limit – they are COMPLETELY covered with shell. No predators… no way. But they do have predators – we will talk more on that.

An assortment of bivalves, mostly bay scallop.

Photo: Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

As you might expect, with the increase in shell there is a decrease in locomotion – as a matter of fact, many species do not move at all (they are sessile). But in a sense, they do not care. They are completely covered and protected. Again, we will talk more about how well that works.

The two shells (valves) are connected on the dorsal side of the animal and hinged together by a ligament. Their bodies are laterally compressed to fit into a shell that is aerodynamic for burrowing through soft muds and sands. Their “heads” are greatly reduced (even missing in some) but they do have a sensory system. Along the edge of the mantle chemoreceptive cells (smell and taste) can be found and many have small ocelli, which can detect light. The scallops take it a step further by having actually eyes – but they do live on the surface and they do move around – so they are needed.

The shells are hinged together at the umbo with “teeth like structures and the shells open and close using a pair of adductor muscles. Many shells found on the beach will have “scars” which are the point of contact for these muscles. They range is size from the small seed clams (2mm – 0.08”) to the giant clam of the Indo-Pacific (1m – 3.4 ft) and 2500 lbs.! Most Gulf bivalves are more modest in size.

Being slow burrowing benthic animals, sand and mud can become a problem when feeding and breathing. In response, many bivalves have developed modified gills to help remove this debris, and many actually remove organic particles using it as a source of food. Many others will fuse their mantle to the shell not allowing sediment to enter. But some still does and, if not removed, will be covered by a layer of nacreous material forming pearls. All bivalves can produce pearls. Only those with large amounts of nacreous material produce commercially valuable ones.

Coquina are a common burrowing clam found along our beaches.

Photo: Flickr

Another feature is the large foot, used for digging a burrowing in the more primitive forms. It is the foot we eat when we eat clams. They can turn their bodies towards the substrate, begin digging with their foot but also using their excurrent from breathing to form a sort of jet to help move and loosen the sand as they go – very similar to the way we set pilings for piers and bridges today.

These are the earliest forms of bivalves – the burrowers. Most are known as clams and most live where the sediment is soft. Located near their foot is a sense organ called a statocyst that lets them know their orientation in the environment. Most have their mantles fused to their shells so sand cannot enter the empty spaces in the body. To channel water to the gills, they have developed tubes called siphons which act as snorkels. Most burrow only a few inches, some burrow very deep and they are even more streamlined and elongated.

Some have evolved to burrow into harder material such as coral or wood. One of the more common ones is an animal called a shipworm. Called this by mariners because of the tunnels they dig throughout the hulls of wooden ships, they are not worms but a type of clam that have learned to burrow through the wood consuming the sawdust of their actions. They have very reduced shells and a very long foot.

This cluster of green mussels occupies space that could be occupied by bivavles like osyters.

Other bivalves secrete a fibrous thread from their foot that is used to grab, hold, and sometimes pull the animal along. These are called byssal threads. Many will secrete hundreds of these, allow them to “tan” or dry, reduce their foot, and now are attached by these threads. The most famous of this group are the mussels. Mussels are a popular seafood product and are grown commercial having them attach to ropes hanging in the water.

Another method of attachment is to literally cement your self to the bottom. Those bivalves who do this will usually lay on their side when they first settle out from their larval stage and attach using a fluid produced by the animal. This fluid eventually cements them to the bottom and the shell attached is usually longer than the other side, which is facing the environment. The most famous of these are the oysters. Oysters basically have lost both their “head” and the foot found in other bivalves. These sessile bivalves are very dependent on tides and currents to help clear waste and mud from their bodies.

Oysters are a VERY popular seafood product along the Gulf coast.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Then there are the bivalves who actually live on the bottom – not attached – and are able to move, or even swim. Most of these have well developed tentacles and ocelli to detect danger in the environment and some, like the scallops, can actually “clap their shells together” to create a jet current and swim. This is usually done when they detect danger, such as a starfish, and they have been known to swim up to three feet. Some will use this jet as a means of digging a depression in the sand they can settle in. In this group, the adductor has been reduced from two (the number usually found in bivalves) to one, and the foot is completely gone.

As you might guess, reproduction is external in this group. Most have male and female members but some species (such as scallops and shipworms) are hermaphroditic. The gametes are released externally at the same time in an event called a mass spawning. To trigger when this should happen, the bivalves pay attention to water temperature, tides, and pheromones released by the opposite sex or by the release of the gametes themselves.

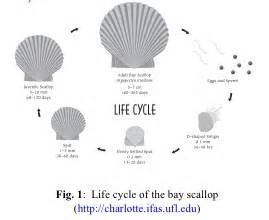

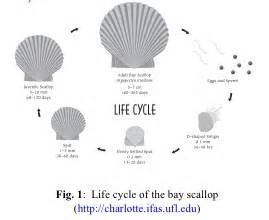

Scallop life cycle.

Image: University of Florida IFAS

The fertilized eggs quickly develop into a planktonic larva known as a veliger. This veliger is ciliated and can swim with the current to find a suitable settling spot. Some species have long lived veliger stages. Oysters are such and the dispersal of their veliger can travel as far as 800 miles! Once the larval stage ends, they settle as “spat” (baby shelled bivalves) on the substrate and begin their lives. Some species (such as scallop) only live for a year or two. Others can live up to 10 years.

As a group, bivalves are filter feeders, filtering organic particles and phytoplankton as small as 1 micron (1/1,000,000-m… VERY small). In doing this they do an excellent job of increasing water clarity which benefits many other creatures in the community. As a matter of fact, many could not survive without this “eco-service” and the loss of bivalves has triggered the loss of both habitat and species in the Gulf region. Restoration efforts (particularly with oysters) is as much for the enhancement of the environment and diversity as it is for the commercial value of the oyster.

Now… predators… yes, they have many. Though they have completely covered their bodies with shell, there are many animals that have learned to “get in there”. Starfish and octopus are famous for their abilities to open tightly closed shells. Rays, some fish, and some turtles and birds have modified teeth (or bills) to crush the shell or cut the adductor muscle. Sea otters have learned the trick to crush them with rocks and some local shorebirds will drop them on roads and cars trying to access them. And then there are humans. We steam them to open the shell and cut their adductor muscle to reach the sweet meat inside.

It is a fascinating group – and a commercial valuable one as well. Lots of bivalves are consumed in some form or fashion worldwide. Take some time at the beach to collect their shells as enjoy the great diversity and design within this group. EMBRACE THE GULF!

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 11, 2020

One of the largest groups of invertebrates in the Gulf are the Mollusk… what many call “seashells”. Shell collecting has been popular for centuries and, in times past, there were large shows where shells from around the world were traded. Almost everyone who visits the beach is attracted to, and must take home, a seashell to remind them of the peace beaches give us. Many are absolutely beautiful, and you wonder how such small simple creatures can create such beauty.

One of the more beautiful shells from the sea – the nautilus.

Photo: Wikipedia

Well, first – not all mollusk are small. There are cephalopods that rival the size of some sharks and even whales.

Second, many are not that simple either. Some cephalopods are quite intelligent and have shown they can solve problems to reach their food.

But beautiful they are, and the colors and shapes are controlled by their DNA. Just amazing.

There are possibly as many as 150,000 different species of mollusks. These species are divided into 8-9 classes (depending which book you read) but for this series on Embracing the Gulf we will focus on only three. First up – the snails (Class Gastropoda).

There are an estimated 60,000 – 80,000 species of gastropods, second only to the insects. They are typically called snails and slugs and are different in that they produce a single coiled shell. The shell is made of calcium carbonate (limestone) and is excreted from tissue called the mantle. It covers their body and continues to grow as they do. The shell coils around a linear piece of shell called the columella. Most coil to the right, but some to the left – sort of like right and left-handed people. There is an opening in the shell where the snail can extend much of its body – this is called the aperture – and some species can close this off with a bony plate called an operculum when they are inside. Some snail shells have a thin extension near the head that protects the siphon – a tube that acts like a snorkel drawing water in and out of the body.

The black siphon can be seen in this crown conch crawling across the sand.

Photo: Franklin County Extension.

They have pretty good eyes and excellent sense of smell. They possess antenna, which can be tactile or sense chemicals in the water (smelling) to help provide information to a simple brain.

They are slow – everyone knowns this – but they really don’t care. Their thick calcium carbonate shells protect them from most predators in the sea… but not all.

Their cousins the slugs either lack the shell completely, or they have a remnant of it internally. You would think “what is the point of an internal shell?” – good question. But the slugs have another defense – they are poisonous. Venomous and poisonous are two different things. Being poisonous means you have a form of toxin within your body tissue. If a predator eats you – they will get very sick, maybe die. But you die as well, so… Not too worry, poisonous slugs are brightly colored – a universally understood signal to all predators.

There is one venomous snail – the cone snail, of which we have about five species in the Gulf. They possess a stylet at the tip of their siphon (similar to the worms we have been writing about) which they can use as a dart for prey such as fish. Many gastropods are carnivores, but some are herbivores, and some are scavengers.

Many shells are found on the beach as fragments. Here you see the fragment of a Florida Fighting Conch.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Most have separate sexes and exchange gametes in a sack called a spermatophore. Fertilized eggs are often encased in structures that resemble clusters, or chains, of plastic. These are deposited on the seafloor and the young are born with their shell ready for life.

This group is not as popular as a food item as other mollusk but there are some. The Queen Conch is probably of the most famous of the edible snails, and escargot are typically land snails. I am not aware of any edible slugs… and that is good thing.

Some of the more common snails you will find along our portion of the Gulf of Mexico are:

Crown Conch Olive Murex Banded Tulip

Whelks Cowries Bonnets Cerith

Slippers Moon Oyster Drills Bubble

The most encountered slug is the sea hare.

A common sea slug found along panhandle beaches – the sea hare.

I hope you get a chance to do some shelling – I hope you find some complete ones. It is addictive!

by Carrie Stevenson | Jun 4, 2020

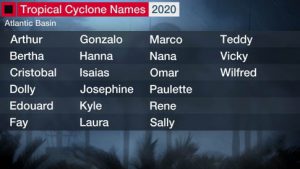

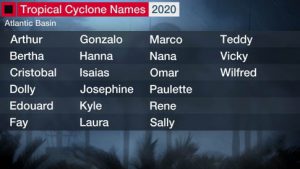

The lineup of 2020 tropical storm names. Tropical storm “Cristobal” is currently headed towards the northern Gulf of Mexico. Photo credit: The Weather Channel

This past March, many people spoke about sensing a sort of free-floating anxiety, waiting for potential disaster to land at their doorstep. The unknowns we faced as COVID-19 cases increased in the United States were not quite like anything we’d previously experienced, although it felt comparable to knowing a hurricane was about to make landfall. After this virus, perhaps, a hurricane seems like a relief—at least we know what to expect and approximately where the most damage will occur. However, big tropical storms carry with them their own set of unpredictable factors like direction and strength at landfall. But the storm-hardiness of our homes, our tree choices, smart evacuation plans—these we can control. Well-thought out precautions can make the difference between getting right back on your feet after a storm and losing almost everything.

Aluminum shutters are one of the many preventative measures Florida homeowners can include in their hurricane preparedness.

Photo: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

No matter how well you have planned for a hurricane, unexpected issues always come up. However, being ready can cut down on the fear and worry.

A few of those preparedness factors include:

* An evacuation plan

* A hurricane kit

* Home wind mitigation techniques

* Tree evaluation

* Wind/flood insurance

I will discuss each of these topics in depth over the next few weeks. Particularly if you are new to the area or never experienced a hurricane, be sure to review good readiness websites, check out these apps, and see which tips might be the most useful to you and your family as we enter the already-active 2020 hurricane season.

by Rick O'Connor | May 27, 2020

As we continue our series on marine life in the Gulf of Mexico, we also continue our articles on marine worms. Worms are not the most charismatic creatures in the Gulf, but they are very common and play a large role on how life functions in this environment. Roundworms are VERY common. There are at least three phyla of them but here we will focus on one – the nematodes.

A common nematode.

Photo: University of Florida

Most nematodes are microscopic, a large one would be about 2 inches, and some beach samples have found as many as 2 million worms in 10 ft2 of sand. So, what do we know about them? What role, or function, do they play in the ecology of the Gulf of Mexico?

Well first, they are long and round – cylinder shaped. There is a head end, but it is hard to tell which end is the head. Round is considered a step up from being flat in that it can allow for an internal body cavity. An internal body cavity can allow for the development of internal body organs. Internal body organs can move large amounts of nutrients, blood, oxygen, and hormones around the body allowing the animal to become larger. Some argue that a larger body can have advantages over smaller ones. Some say the opposite, but either way – a large body has been successful for some creatures and an internal body cavity is needed for this.

That said, the nematodes do not have a complete internal body cavity. So, they do not have a complete assortment of internal organs. Being round reduces your efficiency in absorbing enough needed nutrients, oxygen, etc. through your skin alone and this MAY be a reason they are small. They are very small.

There are free living and parasitic forms in this group. There are at least 10,000 species of them, and they can be found not only in the marine environment, but also in freshwater and in the soil found on land. They have played a role in the success of agriculture, infesting both crops and livestock. Nematodes can be a big concern for farmers and gardeners.

The free-living forms are known to be carnivorous, feeding on smaller microscopic creatures. They have toothed lips, and some have a sharp stylet to grab or stab their prey. Some stylets are hollow and can “suck” their prey in. Moving through the environment, they can consume algae, fungi, and diatoms. Some are deposit feeders and others are decomposers. On our farms and in our gardens, they are known to enter plants via the roots and can be found in the fruit.

The life cycle of the human hookworm.

Image: CDC

The parasitic version of nematodes has been a problem for some species. In humans we have the hookworms and pinworms. Dogs have their heart worms. An interesting twist on the parasitic nematode way of life, compared to flatworms like tapeworms, is their lack of a secondary (or intermediate host). The entire life cycle can take place in the same animal.

Females are larger than males and fertilizations is internal. Males are usually “hooked” at the tail end and hold on to the females during mating. About 50 eggs will be produced and released into the digestive tract, where they exit the animal in the feces and find new hosts either by the feces being consumed or drifting in the water column.

There multiple forms of parasitism in nematodes.

– Some are ectoparasites (outside of the body) on plants.

– Some are endoparasites in plants – some forming galls on the leaves.

– Some infest animals but only as juveniles.

– Some live-in plants as juveniles and animals as adults.

– Some live-in animals as juveniles and plants as adults.

It would be fair to say that many forms of marine creatures have nematodes living either within them, or on them. Some can be problematic and cause disease; some diseases can be quite serious. Others play an important role in “cleaning” the ocean, filtering the sand of organic debris. Many have heard of nematodes but know little about them. Either good or bad, they do play roles in the ecology of the Gulf of Mexico.

by Rick O'Connor | May 14, 2020

As we embrace the marine life of the Gulf of Mexico during this year of “Embracing the Gulf”, we are currently hooked on worms. In the last article we talked about the gross and creepy flatworms. Gross because they are flat, pale in color, only have a mouth so they have to go to the bathroom using it – and creepy in that many of them are parasites, living in the bodies over vertebrates (particularly fish) and that is just creepy. You may ask why would we even “embrace” such a thing? Well… because they do exist and most of us know nothing about them.

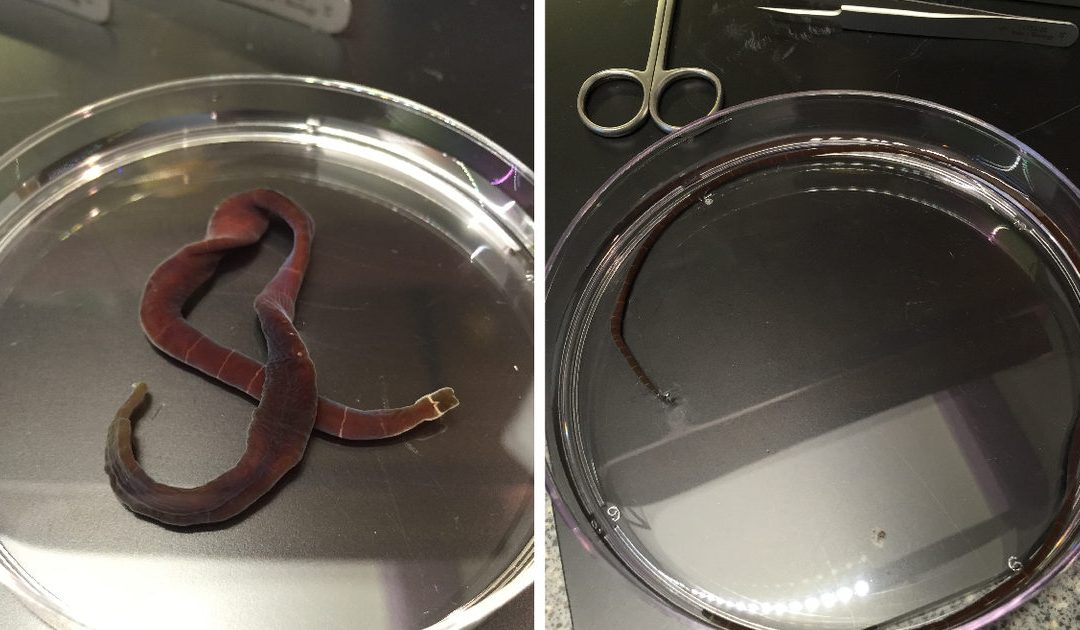

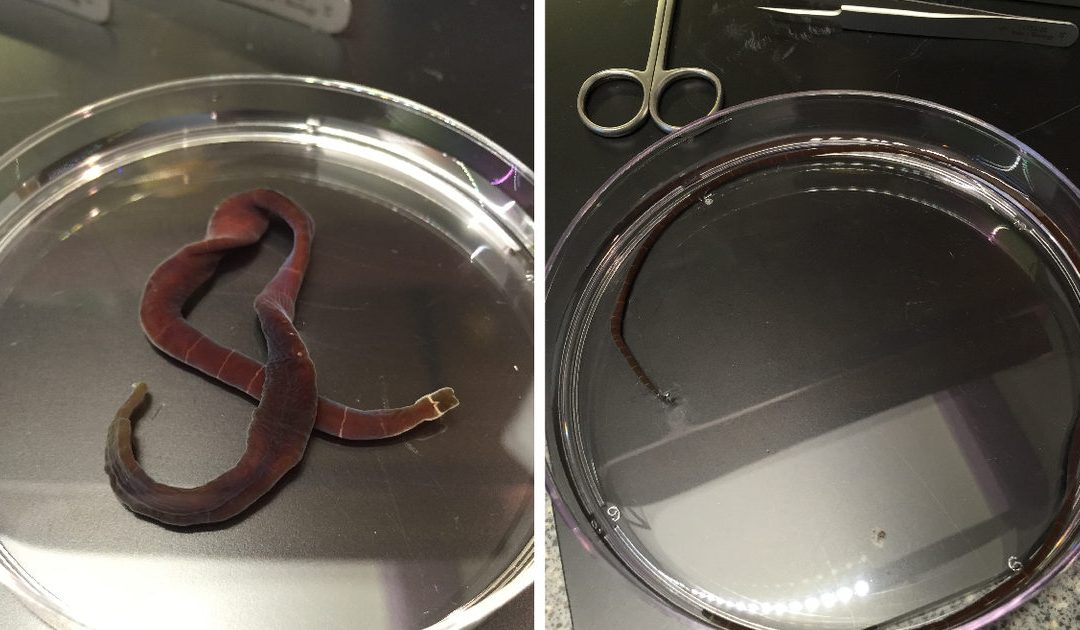

A nemertean worm.

Photo: Okinawa Institute of Science

This week we continue with worms. We continue with a different kind of flatworm. They are not as gross, but maybe a little creepy. They are called nemertean worms and I am pretty sure (a) you have never heard of them, and (b) you have never seen one. So why “embrace” these? Well… again it is education. They do exist, and one day you MAY see one – and know what you are looking at.

Nemerteans are flatworms. They are usually pale in color but a different from the classis fluke or tapeworm in a couple of ways.

1) They do have a way for food to enter and another for waste to leave, what we call a complete digestive tract – and that’s nice.

2) They have this long extension connected to their head called a proboscis. Many of them have a dart at the end they can use to kill their prey – and that’s creepy.

3) And as mentioned, most are carnivores, feeding on small invertebrates – and that’s okay.

We rarely see them because they are nocturnal – hiding under rocks, shells, seaweed during the day and hunting at night. Most are about eight inches long but some in the Pacific reach almost eight feet!

I would put that in the creepy file.

As we said, they are usually pale in color, though some may have yellow, orange, red, or even green hues to them. Their heads are spade shaped and, again, hold a retracted proboscis. This proboscis can be over half the length of the worm. At the end is a stylet (a dart) which they can use to stab their prey (small invertebrates). They can stab repeatedly, like using a knife, – they may stab and grab, like using a claw – or they may be a species that has toxin and kills their prey that way.

Nice.

Some would add this to the creepy file as well. A long pale worm, moving at night, extending a long proboscis when they get near you with a sharp dart at the end they essentially “sting” you like a bee.

Yea, creepy.

But we NEVER hear about such things with humans. They hunt small invertebrates like amphipods, isopods, and things like that. If you picked one up, would it stick the dart in you? My hunch would be yes – I honestly don’t know, I have only seen one to two in the 35+ years I have been teaching marine science and I did not pick them up. I have never met anyone who has and have never read “DON’T PICK THESE UP – VERY DANGERSOUS”. So, my hunch is that it would not be very painful at all.

But don’t take my word for it – again, I have rarely seen one… so, don’t pick them up 😊

There are about 650 species of nemertean worms in the world, 22 live in the Gulf of Mexico, and 16 live in the northern Gulf (near us). They are basically marine, move across the environment on their slime trails, seeking prey primarily by the sense of smell at night. Unlike the flukes and tapeworms, there are male and females in this group. They fertilize their eggs externally to make the next generation of these harpooning hunters of the Gulf.

I don’t know if you will ever come across one of these. You will know it by the flat body, pale color, and spade-shaped head, but I think it would be pretty neat to find one. There are more worms to learn about in the Gulf of Mexico, but we will do that in another edition.

by Chris Verlinde | May 1, 2020

Black Skimmers foraging for fish. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

Black Skimmers and Least Terns, state listed species of seabirds, have returned along the coastal areas of the northern Gulf of Mexico! These colorful, dynamic birds are fun to watch, which can be done without disturbing the them.

Shorebirds foraging. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

Black Skimmer with a fish. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

What is the difference between a seabird and shorebird?

Among other behaviors, their foraging habits are the easiest way to distinguish between the two. The seabirds depend on the open water to forage on fish and small invertebrates. The shorebirds are the camouflaged birds that can found along the shore, using their specialized beaks to poke in the sandy areas to forage for invertebrates.

Both seabirds and shorebirds nest on our local beaches, spoil islands, and artificial habitats such as gravel rooftops. Many of these birds are listed as endangered or threatened species by state and federal agencies.

Juvenile Black Skimmer learning to forage. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

Adult black skimmers are easily identified by their long, black and orange bills, black upper body and white underside. They are most active in the early morning and evening while feeding. You can watch them swoop and skim along the water at many locations along the Gulf Coast. Watch for their tell-tale skimming as they skim the surface of the water with their beaks open, foraging for small fish and invertebrates. The lower mandible (beak) is longer than the upper mandible, this adaptation allows these birds to be efficient at catching their prey.

Least Tern “dive bombing” a Black Skimmer that is too close to the Least Tern nest. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

Adult breeding least terns are much smaller birds with a white underside and a grey-upper body. Their bill is yellow, they have a white forehead and a black stripe across their eyes. Just above the tail feathers, there are two dark primary feathers that appear to look like a black tip at the back end of the bird. Terns feed by diving down to the water to grab their prey. They also use this “dive-bombing” technique to ward off predators, pets and humans from their nests, eggs and chicks.

Least Tern with chicks. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

Both Black Skimmers and Least Terns nest in colonies, which means they nest with many other birds. Black skimmers and Least Terns nest in sandy areas along the beach. They create a “scrape” in the sand. The birds lay their eggs in the shallow depression, the eggs blend into the beach sand and are very hard to see by humans and predators. In order to avoid disturbing the birds when they are sitting on their nests, known nesting areas are temporarily roped off by Audubon and/or Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) representatives. This is done to protect the birds while they are nesting, caring for the babies and as the babies begin to learn to fly and forage for themselves.

Threats to these beautiful acrobats include loss of habitat, which means less space for the birds to rest, nest and forage. Disturbances from human caused activities such as:

- walking through nesting grounds

- allowing pets to run off-leash in nesting areas

- feral cats and other predators

- litter

- driving on the beach

- fireworks and other loud noises

Audubon and FWC rope-off nesting areas to protect the birds, their eggs and chicks. These nesting areas have signage asking visitors to stay out of nesting zones, so the chicks have a better chance of surviving. When a bird is disturbed off their nest, there is increased vulnerability to predators, heat and the parents may not return to the nest.

Black Skimmer feeding a chick. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

To observe these birds, stay a safe distance away, zoom in with a telescope, phone, camera or binoculars, you may see a fluffy little chick! Let’s all work to give the birds some space.

Special thanks to Jan Trzepacz of Pelican Lane Arts for the use of these beautiful photos.

To learn about the Audubon Shorebird program on Navarre Beach, FL check out the Relax on Navarre Beach Facebook webinar presentation by Caroline Stahala, Audubon Western Florida Panhandle Shorebird Program Coordinator:

In some areas these birds nest close to the road. These areas have temporarily reduced speed limits, please drive the speed limit to avoid hitting a chick. If you are interested in receiving a “chick magnet” for your car,  to show you support bird conservation, please send an email to: chrismv@ufl.edu, Please put “chick magnet” in the subject line. Please allow 2 weeks to receive your magnet in the mail. Limited quantities available.

to show you support bird conservation, please send an email to: chrismv@ufl.edu, Please put “chick magnet” in the subject line. Please allow 2 weeks to receive your magnet in the mail. Limited quantities available.