by Ray Bodrey | Jul 11, 2022

The University of Florida/IFAS Extension faculty are reintroducing their acclaimed “Panhandle Outdoors LIVE!” series. Conservation lands and aquatic systems have vulnerabilities and face future threats to their ecological integrity. Come learn about the important role of these ecosystems.

The St. Joseph Bay and Buffer Preserve Ecosystems are home to some of the one richest concentrations of flora and fauna along the Northern Gulf Coast. This area supports an amazing diversity of fish, aquatic invertebrates, turtles, salt marshes and pine flatwoods uplands.

This one-day educational adventure is based at the St. Joseph Bay State Buffer Preserve near the coastal town of Port. St. Joe, Florida. It includes field tours of the unique coastal uplands and shoreline as well as presentations by area Extension Agents.

Details:

Registration fee is $45.

Meals: breakfast, lunch, drinks & snacks provided (you may bring your own)

Attire: outdoor wear, water shoes, bug spray and sun screen

*if afternoon rain is in forecast, outdoor activities may be switched to the morning schedule

Space is limited! Register now! See below.

Tentative schedule:

All Times Eastern

8:00 – 8:30 am Welcome! Breakfast & Overview with Ray Bodrey, Gulf County Extension

8:30 – 9:35 am Diamondback Terrapin Ecology, with Rick O’Connor, Escambia County Extension

9:35 – 9:45 am Q&A

9:45- 10:20 am The Bay Scallop & Habitat, with Ray Bodrey, Gulf County Extension

10:20 – 10:30 am Q&A

10:30 – 10:45 am Break

10:45 – 11:20 am The Hard Structures: Artificial Reefs & Marine Debris, with Scott Jackson, Bay County Extension

11:20 – 11:30 am Q&A

11:30 – 12:05 am The Apalachicola Oyster, Then, Now and What’s Next, with Erik Lovestrand, Franklin County Extension

12:05 – 12:15 pm Q&A

12:15 – 1:00 pm Lunch

1:00 – 2:30 pm Tram Tour of the Buffer Preserve (St. Joseph Bay State Buffer Preserve Staff)

2:30 – 2:40 pm Break

2:40 – 3:20 pm A Walk Among the Black Mangroves (All Extension Agents)

3:20 – 3:30 pm Wrap Up

To attend, you must register for the event at this site:

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/panhandle-outdoors-live-at-st-joseph-bay-tickets-404236802157

For more information please contact Ray Bodrey at 850-639-3200 or rbodrey@ufl.edu

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 18, 2022

When you look over the species of sea basses and groupers from the Gulf of Mexico it is a very confusing group. Hoese and Moore1 mention the connections to other families and how several species have gone through multiple taxonomic name changes over the years – its just a confusing group.

Gag grouper.

Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

But when you say “grouper” everyone knows what you are talking about, and everyone wants a grouper sandwich. This became a problem because what people were serving as “grouper” may not have been “grouper”. And as we just mentioned what is a grouper anyway? The families and genera have changed frequently. Well, this will probably get more technical than we want, but to sort it out – at least using the method Hoese and Moore did in 1977 – we will have to get a bit technical.

“Groupers” are in the family Serranidae. This family includes 34 species of “sea bass” type fish. Serranids differ from snappers in that they lack teeth on the vomer (roof of their mouths) and they differ from “temperate basses” (Family Percichthyidae) in that their dorsal fin is continuous, not separated into two fins. These are two fish that groupers have been confused with.

Banked Sea Bass.

Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

We can subdivide the serranids into two additional groups. The “sea basses” have fewer than 10 spines in their dorsal fin. There are 10 genera and 18 species of them. They have common names like “bass”, “flags”, “barbiers”, “hamlets”, “perch”, and “tattlers”. They are small and range in size from 2 – 18 inches in length. Most are bottom reef fish with little commercial value for fishermen. Most are restricted to the tropical parts of the Atlantic basin but two are only found in the northwestern Gulf, one is only found in the eastern Gulf, and one has been found in both the Atlantic and Pacific. The biogeography of this group is very interesting. The same species found in both the Atlantic and Pacific suggest an ancient origin. The variety of serranid sea bass suggest a lot of isolation between groups and a lot of speciation.

The ”groupers” have 10 or more spines in their dorsal fin. There are two genera in this group. Those in the genus Epinephelus have 8-10 spines in their anal fin and have some canine teeth. Those in the genus Mycteroperca have 10-12 spines in their anal fin and lack canine teeth. Within these two genera there are 15 species of grouper, though the common names of “hind”, “gag”, “scamp” are also used. Most of these are found along the eastern United States and Gulf of Mexico. Five species are only found in the tropical parts of the south Atlantic region, five are also found across the Atlantic along the coast of Africa and Europe, and – like the “sea bass” two have been found in both the Atlantic and the Pacific. They range in size from six inches to seven feet in length. The Goliath Grouper can obtain weights of 700 pounds! Like the sea bass, groupers prefer structure and can live a great depths. Unlike sea bass they are heavily sought by commercial and recreational anglers and are one of the more economically important groups of fish in the Gulf of Mexico.

The massive size of a goliath grouper. Photo: Bryan Fluech Florida Sea Grant

One interesting note on this family of fish is that most are hermaphroditic. The means they have both ovaries (to produce eggs) and testes (to produce sperm). Sequential hermaphrodism is when a species is born one sex but becomes the other later in life. This is the case with most groupers, who are born female and become male later in life. However, the belted sand bass (Serranus subligarius) is a true hermaphrodite being able to produce sperm and egg at the same time – even being able to self-fertilize.

For many along the Florida panhandle, their biogeographic distribution and sex do not matter. It is a great tasting fish and very popular with anglers. For those with a little more interest in natural history of fish in our area, the biology and diversity of this group is one of the more interesting ones.

Reference

1 Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 11, 2022

Snook… Wait did you say Snook in the Florida panhandle?

Yep… they are not common, but they have seen here.

For those who do not know the fish and do not understand why seeing them is strange, this is a more tropical species associated with tarpon. In the early years of tourism in Florida tarpon fishing was one of the main reasons people came. Though bonefish and snook fishing were not has popular as tarpon, they were good alternatives and today snook fishing is popular in central and south Florida… but not in the north.

This snook was captured near Cedar Key. These tropical fish are becoming more common in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

Photo: UF IFAS

This fish is extremely sensitive to cold water, not liking anything under 60° F. They frequent the same habitats as tarpon, mangroves and marshes. They are euryhaline (having a wide tolerance for salinity) and can be found in freshwater rivers and springs. Actually, near river mouths is a place they frequent. The younger fish are more often found within the estuaries and adults have been found in the Gulf of Mexico. Again, this is a more tropical fish with records in Florida north of Tampa being rare. In the western Gulf the story is the same, almost all records are south of Galveston, Texas. Until recently…

Hoese and Moore1 cite a paper by Baughman (1943) that indicated the range of the fish had actually moved further south. One reason given was the loss of the much-needed salt marsh and mangrove habitats from human development. But in recent years there have more reports north of Tampa. Purtlebaugh (et al.)2 published a paper in 2020 indicating an increase in snook captured in the Cedar Key area of the Big Bend beginning in 2007. At first records only included adults, and the thought was these were “wayward” drifters in the region. But by 2018 they were capturing fish in all size classes and there was evidence of breeding going in the area. The range of the fish seemed to be moving north. The study suggests they still need warm water locations to over winter, and, like the manatees, springs seem to be working fine. But another piece of the explanation has been the reduction of hard freezes during winter in this part of the Gulf. Climate change may be playing a role here as well.

There seems to be other tropical species dispersing northward in a process some call “tropicalization” including the mangroves. There have been anecdotal reports of snook near Apalachicola where mangroves are becoming more common, and I know of two that were caught in Mobile Bay. There are mangroves growing on the Mississippi barrier islands as well. While explaining this during a presentation I was doing for a local group, a gentleman showed me a photo of a snook on his phone. I asked if he caught it in the Pensacola area. He replied yes. When I asked where, he just smiled… 😊 He was not going to share that. Cool.

There is no evidence that snook have established breeding populations are in our waters. Especially after this winter with multiple days with temperatures in the 30s, it is unlikely snook would be found here. But it is still interesting, and we encourage anyone who does catch one, to report it to us.

References

1 Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station Tx. Pp 327.

2 Purtlebaugh CH, Martin CW, Allen MS (2020) Poleward expansion of common snook Centropomus undecimalis in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico and future research needs. PLoS ONE 15(6): e0234083. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234083.

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 3, 2022

Seahorses are one of the coolest creatures on this planet – period. I mean who doesn’t like seahorses? People state “I love snakes”, “I hate snakes”, “I love sharks”, “I hate sharks”. But no one says, “I hate seahorses”. They are sort of in the same boat with sea turtles, everyone loves sea turtles. They are an icon of the sea, logos for beach products and coastal HOAs, underwater cartoons and tourist development boards, diving clubs and local restaurants. But have you ever seen one? I mean beyond seeing one at a local aquarium or such, have you ever found one while snorkeling on one of our beaches?

Most would say no.

I have lived in the panhandle all my life and have spent much of it in the water, and I can count on both hands the number of times I have encountered a seahorse while at the beach. Most encounters have been while seining. I cannot count on both hands how many times I have pulled a seine net here but very few of them did a seahorse encounter occur. When they did, it was over grassbeds. In each encounter the animal was lying in the grass not wriggling like the other fish, just lying there. It would be very easy to miss them discarding it as “grass”. It makes you wonder how many times I captured one and did not know it. When we did find one it was VERY exciting. My students would often scream “I had NO idea they lived here!”.

The seahorse Photo: NOAA

However, if you tried searching for them while snorkeling, which I have, the encounter rate is zero. But this makes sense. These animals are so well camouflaged in the grass it would be a miracle to find one just hanging there. This is by necessity really. If you have ever watched a seahorse in an aquarium they are not very “fleet of foot”. Escaping a predator by dashing away is not one of their finer skills. No, they must blend in and remain motionless if trouble, like a snorkeler, comes by.

But I have seen one while diving. It was a night dive near the Bob Sikes Bridge on Pensacola Beach about 40 years ago. We were exploring when my light swung over to see this large seahorse extended from a pipe that was coming out of some debris on the bottom. I was jubilated and screamed, as best you can while using SCUBA, for my partners to come check this out. We were all amazed and my interest in these animals increased.

When I attended Dauphin Island Sea Lab (DISL) as an undergraduate student, like many in the 1970s, I thought I would get involved with sharks, but I quickly developed a love for estuaries and my interest in seahorses returned. I made a visit to the library there and found very little in the literature, at that time, which piqued my interest even more. My senior year we had to complete a project where we had to collect, and correctly identify, 80 species of fish to pass the class. I asked the crew of the research vessel at DISL if they had ever found seahorses. They responded yes and took me to what they called their “seahorse spot”. We caught some. It was very cool. And yes… seahorses do exist here in the wild.

But what is this amazing animal?

What do I mean by this? As a marine science instructor, I would give my students what are called a lab practical’s. Assorted marine organisms would be scattered around the room and the students had to give their common name, phylum name, class name, and answer some natural history question I would ask. Snails are mollusk, mackerel are fish, jellyfish are cnidarians, and then they would come to the seahorse. Seahorses were… well… seahorses! What the heck are they?

Many of you may know they are fish. But over the years of teaching marine science, I found that many students were not sure of that. The definition of a fish is an animal with a backbone that possesses a scaly body, paired fins (usually), and gills. Seahorses have all that. There is a backbone no doubt. The scales are not as obvious because they are actually fused together in a sort of armor. The paired fins and gills are there. Yep… they are fish, but a fish (horse) of a different color.

This seahorse is a species from Indonesia.

Photo: California Sea Grant.

First, they are one of about 13 families of fish in the Gulf of Mexico that lack ventral fins, those on the belly side of their bodies. Second, they lack a caudal fin (the fish tail) and have a more prehensile tail for grabbing objects. Third, they swim vertically instead of horizontally as most fish do. Again, there is nothing about their body design that says “speed”.

Another thing I find fascinating about these animals is their global distribution. You might recall that the initial focus of this series on Florida panhandle vertebrates was the biogeography of these creatures. Seahorses are found all over the world. There are over 350 species of them. But the interesting question is: how would a seahorse living in the northern Gulf of Mexico reach Melbourne Australia? It makes sense that being so far apart there would be such differences in looks and genetics that they would be classified as different species, but how did an animal like a seahorse disperse across a large ocean like the Pacific?

Honestly, I can say the same for ghost crabs, which I found on the beaches of Hawaii. How did they get there? But that is another story.

My best guess was the dispersal occurred at a time when the two continents were closer together. The Pangea days, or some time close to that period. And as the continents “drifted” the seahorses remained close to their shorelines and moved apart. They may have been able to “island hop” across coral reefs to other Indonesian Islands, but those here in the United States were long lost relatives that changed in their appearance and lifestyles due to the large separation from others. That is my two cents anyway.

Hoese and Moore1 list two species of seahorses found here in the northern Gulf of Mexico. The Lined Seahorse and the Dwarf Seahorse.

The Lined Seahorse (Hippocampus erectus) is the larger of the two, reaching an average length of five inches. This is the one I found near the Bob Sikes Bridge all those years ago. Like all seahorses they are well adapted to life in debris where they can grab on to something with their prehensile tail and feed on small zooplankton using their vacuum like tube snout. Like all seahorses, the males have a brood pouch that holds the fertilized eggs producing live birth – another “live bearer”. They are usually dark in color, but gold individuals have been reported. Some have filamentous threads on their bodies making them look even more like plants. Their biogeographic distribution is amazing. They are found from Nova Scotia, throughout the tropics, all the way to Argentina. This suggests few biogeographic barriers, other than substrate to hide in.

The Dwarf Seahorse (Hippocampus zosterae) – also known as the pygmy seahorse – is much smaller, with a mean length of 1.5 inches. That would qualify as “dwarf” or “pygmy”. How would you ever find these? Other than size, the difference between these two are the number of rays (soft spines) in their fins. They can be counted, but its not fun, especially with a 1.5” seahorse. This guy prefers high salinity, actually, I have found that most seahorses do. This one is more tropical in distribution.

There is a third Florida species, the long snout seahorse (Hippocampus redi) that is found on the Atlantic coast, but not in the Gulf.

The strange thing about the seahorses in Florida, has been the declining encounters over the last few decades. For a creature that seems to have few barriers, they have found trouble somewhere. Maybe the loss of habitat, maybe a population crash due to the common practice years ago of capture and drying out for tourists to buy. It could be a change in environmental conditions such as salinity in the Pensacola Bay area. I am not sure. The more I write this article, the more my interest in this fish returns. As many researchers and wildlife managers have mentioned, this is an animal who has “fallen through the cracks”. People notice the changes in sea turtle and manatee encounters, but not seahorses. Maybe it is time we pay more attention to them and see how they are doing. I for one would hate to see the decline of this creature here in the panhandle.

Reference

Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station, TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 27, 2022

Members of the family Poeciliidae are what many call “livebearers”. Live bearing meaning they do lay eggs as most fish do, but rather give birth to live young. But this is not to be confused with live-bearing you find in mammals – which is different.

Most fish lay eggs. The females and males typically have a courtship ritual that ends with the female’s eggs (roe) being laid on some substrate, or released into the water column, and the male’s sperm (milt) are released over them. Once fertilized the gelatinous covered eggs begin to develop.

Everything the developing young need to survive is provide within the egg. The embryo is suspended in a semi-gelatinous fluid called the amnion. Oxygen and carbon dioxide gas exchange occurs through this amnion and through the gelatinous covering of the egg itself. Food is provided in the form of yolk, which is found in a sac attached to the embryo. There is a second sac, the allantois, where waste is deposited. When the yolk is low and the allantois full – it is time to hatch. This usually occurs in just a few days and often the baby fish (fry) are born with the yolk sac still attached. Parental care is rare, they are usually on their own.

With “livebearers” in the family Poecillidae it is different.

The males have a modified anal fin called a gonopodium. They fertilize the roe not externally but rather internally – more like mammals. The fertilized eggs develop the same as those of other fish. There is a yolk sac and allantois, and the embryo is covered in amnion within the gelatinous egg covering. But these eggs are held WITHIN the female, not laid on the substrate or released into the water column. When they hatch the live fry swim from the mother into the bright new world – hence the term “livebearer”.

There are advantages to this method. The eggs are protected inside the mother, and she obviously provides parental care to her offspring. However, this does make her much slower and an easier target for predators. There is some give and take.

This differs from the “live-bearing” of most mammals in that there is still an egg. Mammals do still have a yolk sac but feeding and removing waste is done THROUGH THE MOTHER. Meaning the embryo is attached to the mother via an umbilical cord where the mother provides food and removes waste trough her placenta. There is no classic egg in this case. I say most mammals because there are two who live in Australia that still do lay eggs – the platypus and the spiny anteater, and the marsupials (kangaroos and opossums) are a little different as well – but marsupials do no lay eggs.

Biologists have terms for these. Oviparous are vertebrates that lay eggs – such as fish, frogs, turtles, and birds. Ovoviviparous are vertebrates that produce eggs but keep them within the mother where they hatch – such as some sharks, some snakes, and the live bearing fish we are talking about here. Then there are the viviparous vertebrates that do not have an egg but rather the embryo is attached, and fed by, the mother herself – like most mammals.

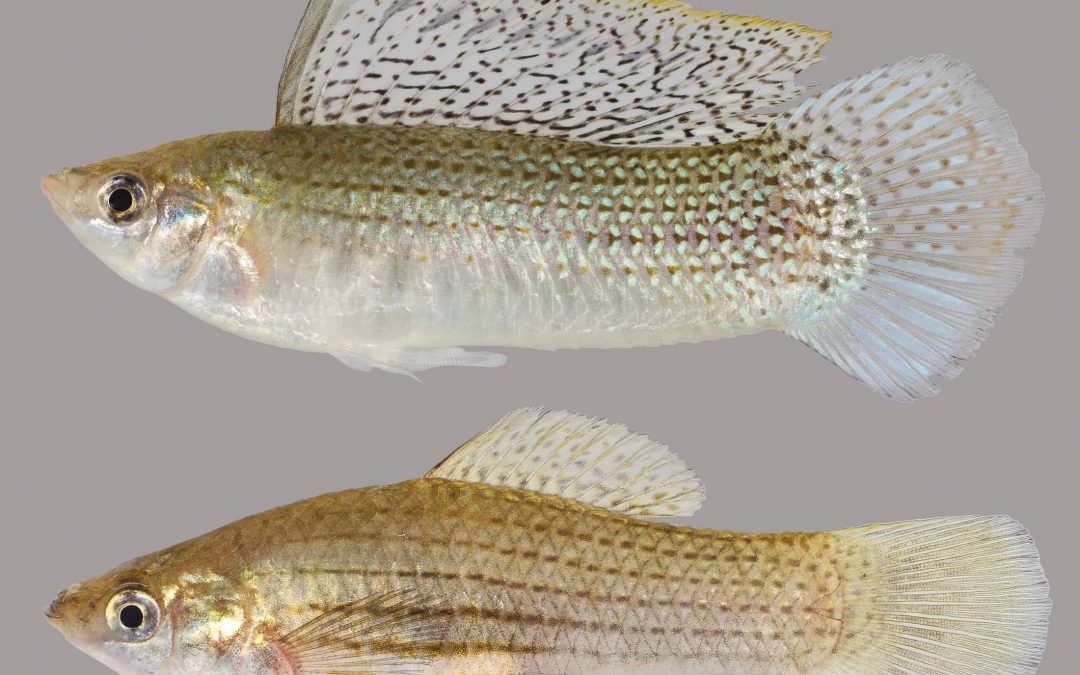

Sailfin Molly. The male is the fish above with the large “sailfin”. Note the gonopodium on his ventral side.

Photo: University of Florida

The livebearers of the family Poeciliidae are ovoviviparous. They are primarily small freshwater fish that are very popular in the aquarium trade. But there are two species that can tolerate saltwater and enter the estuaries of the northern Gulf of Mexico: the sailfin molly and the mosquitofish.

The Sailfin Molly (Poecilia latipinna) is the same fish sold in aquarium stores as the black molly. The black phase is quite common in freshwater habitats, but in the estuarine marshes the fish is more of a gray color with lateral stripes that is made up of a series of dots. They are short-stout bodied fish and the males possess the large sail-like dorsal fin from which the species gets its common name. The females resemble the males albeit no large sailfin and most found are usually round and full of developing eggs. They are very common in local salt marshes and often found in isolated pools within these habitats. The biogeographic range of this species is restricted to the southern United States, reported from South Carolina throughout the Gulf of Mexico. One would guess temperature may be a barrier to their dispersal further north along the Atlantic seaboard.

The mosquitofish.

Photo: University of Florida

The Mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) is familiar to many people whether they know it or not. Those who know the fish know they are famous for the habit of consuming mosquito larva and some, including our county mosquito control unit, use them to control these unwanted flying insects. For those who may they are not familiar with it, this is the fish frequently seen in roadside ditches, ephemeral ponds that show up after rainstorms, retention ponds, and other scattered bodies of freshwater within the community. Most who see them call them “minnows”. There is always the question as to “where did they come from?” You have a vacant lot – it rains one day – these small fish show up – where did they come from? The same can be said for community retention ponds. The county comes in a digs a hole – it rains one day, and the retention pond fills – and there are fish in it. One explanation to their source is the movement of fish by wading birds, where the fish incidentally become attached to their feet. Again, they are often released intentionally to help control local mosquito populations. This fish is found in our coastal estuaries but does not seem to like saltwater as well as the sailfin molly. It is found in cooler water ranging throughout the Gulf and as far north as New Jersey.

Both of these fish make excellent aquarium pets, and the sailfin molly in particular can be beautiful to watch.

Reference

Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 13, 2022

Like many of you reading this article, I grew up here in the northern Gulf coast. I spent a lot of time at the beach and in the water enjoying this fantastic place people use to call the “miracle strip” and now call the “emerald coast”. I would spend hours swimming, fishing, crabbing, skiing (a sport that has all but disappeared around here), and just enjoying this place. With all the fishing and snorkeling we did we were familiar with many species in the area. Pinfish, flounder, mackerel, croaker to name a few. But one group of local fish I was not aware of were the killifish. I was not aware of them until I attended Dauphin Island Sea Lab to study marine biology. And then… I discovered them.

Like many who entered marine biology programs in the 1970s I was going to be an ocean going “Jacques Cousteau” studying sharks or something. But at Dauphin Island I was introduced to the amazing world of the estuary where we did a lot of work in Mobile Bay. Pulling seine nets through the numerous salt marshes over there I quickly found that one of the most abundant fish there were these fish known as killifish. They are small minnow type fish who typically run three inches or so in length. There are two who grow larger, the longnose killifish and the gulf killifish both can reach six inches and are known by local fishermen as “bull minnows”. Bull minnows are popular bait, but most fishermen do not know that the actual name of these fish are killifish. When I was in graduate school, I took a course in aquaculture, and we visited five states in five days stopping at federal, state, and private fish farms. One private farm was a “bull minnow” farm in Arkansas. This farmer was doing quite well. He had a collection of corvettes and was working on a collection of mustangs. Needless to say bull minnows are a popular bait.

But who are these abundant estuarine minnows that most are not aware of?

Well, as we said they are small. For most, their bodies are tube shaped (fusiform) and their fins are rounded, not forked. Rounded fins (truncate) are not designed for speed but for better maneuvering in and around grasses, rocks, and coral. Killifish live in the grasses of seagrass beds and shoreline marshes where these fins come in handy.

Most have an extreme tolerance for changes in salinity. The sheepshead minnow (Cyprinodon variegatus) can live in salinities as low as 0 ppt and as high as 100 ppt – mean seawater salinity is 35 ppt. Because of this high tolerance to salinity changes, many of these killifish can be found in a variety of habitats within the estuary and even in freshwater systems entering the bay. One species, the longnose killifish (Fundulus similis) seems to prefer more saline conditions. Because of this we are looking at a local project to determine which estuarine creeks this species is found. The absence of the longnose killifish could suggest freshwater discharge and, possibly, a run-off issue. But with the dramatic salinity shifts typically seen within estuaries due to tides and run-off, having a high tolerance for salinity shifts is a good adaptation to have.

According to Hoese and Moore1 there are seven species of killifish within the estuaries of the northern Gulf of Mexico.

This longnose killifish has the rounded fins of a bottom dwelling fish.

The longnose killifish (Funuduls similis) is elongated with vertical black stripes and a single dot at the base of the tail. It has an elongated snout that gives the name “longnose”. This is a very common killifish but, as mentioned above, disappears when salinities become too low. According to Hoese and Moore1 this fish is not that common along the Gulf coast of peninsula Florida. The biogeographical reason? Not sure. We know this fish does not like freshwater but the discharge in that part of the Gulf is not that different than the panhandle, in fact, it could more saline.

Saltmarsh topminnow

Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

The saltmarsh topminnow (Fundulus jenkinsi) is not as common. Its geographic range extends from Galveston Bay to the western Florida panhandle. Here in Florida, it is so rare it is a listed species. It resembles the longnose in shape and vertical stripes, which are actually rows of black dots, but the snout is short. I am not sure why this fish has not expanded its range east into the Big Bend or west towards Corpus Christi. Both of those areas seem to be higher in salinity and this may be the reason.

The gulf killifish (Fundulus grandis) is the “big boy” of the group. With a mean length of six inches this fish is often confused with “fingerling mullet” and is very popular as bait. This is the fish most often called “bull minnow”. Young will have dark stripes like the longnose but lack the “longnose” and does not have a black spot at the base of the tail. Most lose their stripes when they become older. It is found throughout the Gulf region.

The bayou killifish (Funudulus pulvereus) is another very common killifish in our area. Smaller than the gulf killifish and longnose, it can be identified by the yellowish colored anal fin. Males will have stripes while females will have spots. The coloration of these is amazing and the breeding colors of the males even more so. Hoese and Moore1 report this fish only from southern Texas to Alabama, but we have often found them here in Pensacola. I am not sure how far east they exist, but there must be some barrier in Florida waters to impede their dispersal there.

Sheepshead Minnow

Photo: University of Florida

The sheepshead minnow (Cyprinodon variegatus) is the champion of salinity tolerance. They are found in many estuarine habitats and even some extreme ones where no other fish are found. Hoese and Moore1 report that it has the highest tolerance of any fish in the world. There are records of this fish living in waters over 100 ppt (note: the average salinity for the ocean is 35 ppt). As you might expect, it has the largest range as well. This fish had been reported from Maine, down the entire east coast, the Gulf of Mexico, and as far south as Venezuela. It is not as elongated as most killifish, having a more short and stout appearance. They have dark vertical bars on their bodies and the males produce a beautiful iridescent blue color on their backs during breeding.

Diamond Killifish

Photo: University of Florida

The diamond killifish (Adinia xenica) is one that I have not collected very often. It resembles the sheepshead minnow is shape and color but has a more pointed snout and the teeth are compressed instead of conical, as they are in the sheepshead minnow. This fish is restricted to the western Gulf of Mexico but is found here in the Florida panhandle. It usually is in a group with other killifish, so, you would have to look hard in your sample to see if you have it.

Rainwater Killifish

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History

Finally, there is the rainwater killifish (Lucania parva). This is a more elongated form with no markings on the body at all. At first glance, after seeing other types of killifish, it would not appear to be a killifish at all. It is one of the smaller killifish (2 inches) and is often found in freshwater creeks feeding into the bays. The males will have a reddish-orange anal fin during breeding season. It does have a large range extending from New England to Mexico.

These are truly amazing fish. They are extremely abundant and hardy. For those prone to use small nets collecting fish along the shorelines, grassbeds, and salt marshes, they will find this group very common, and most do well in aquariums.

Reference

1 Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.