by Rick O'Connor | Aug 4, 2022

Author: Ian Stone – Forestry Extension Agent Walton County

Selecting a consulting forester is often a major decision for small to large private landowners engaged in forest management and enterprises. Consulting foresters provide technical forestry assistance in all aspects of forest management. These professionals can assist landowners by identifying goals and needs and then apply forestry expertise to meet these needs and goals. Consulting foresters are professionals who provide their services for a fee; much like lawyers or engineers. Consulting foresters provide multiple services with various fee structures which can be provided on an hourly, per acre, one-time, or percentage. For example, a herbicide treatment would often be on a per acre basis, while a timber sale would often be done on a percentage. A landowner should always have a consultant provide a scope of work along with the fee structure and estimate. It is advisable that a landowner consult several foresters or firms to compare services and fees before making a selection.

Streamside Management Zone (SMZ) marked prior to harvest so it is clear to the landowner and logger. This service is often performed by a consulting forester as part of timber sale preparation.

(Photo Credit: David Stevens, Bugwood.org Image# 5443305)

Consulting foresters are highly skilled professionals with extensive knowledge in many areas. Examples of required areas of knowledge are timber volume estimation and appraisal, forest management, tree planting and reforestation, prescribed fire, wildlife and habitat management, taxation, estate planning, forest treatment such as mechanical, herbicide, fertilization, and many more. Most consultants are well versed in all aspects of the forestry profession, but often have one or two areas of specialization. A landowner should discuss the services and credentials a forestry consultant or firm provides and select on that best fits their unique needs.

Many states require consulting foresters to become registered or certified through a professional certification board. Florida, however, is an exception to this which means landowners in Florida should thoroughly examine the forester’s professional credentials. Landowners should select a forester with the skills and credentials they require. The two largest professional organizations that set professional expectations for foresters are the Society of American Foresters (SAF) and the Association of Consulting Foresters (ACF) Examples of what to look for in credentialing are as follows:

- A 4-year bachelor’s degree in forestry or a related field; especially form an SAF accredited university forestry program

- Registration or certification in another state or nationally through the SAF Certified Forester

program

- Membership in professional forestry organizations such as ACF or SAF, along with similar

organizations such as Tree Farm, Florida Forestry Association, or Forest Landowners Association

- The ability to clearly communicate with the client and others. Ask for samples of contracts, a

written quote, an in-person meeting, and references from other landowners

- Professional integrity, honesty, and a commitment to ethical practice

Landowners can find listings of Consulting Foresters and firms in their area through multiple sources.

The Florida Forest Service (FFS) maintains an online list of consulting foresters through the FFS Vendor Database (Florida Forest Service Vendor Database (fdacs.gov)).

Landowners can find lists of registered foresters through the Alabama and Georgia boards of forestry. Most consultants close to state boundaries practice in multiple states. In addition, SAF and ACF maintain online listings of consulting foresters and members at large.

Additional Helpful Websites for Locating a Consulting Forester in the Panhandle-

Association of Consulting Foresters- Home (acf-foresters.org)

Alabama Board of Registered Foresters- ASBRF (alabama.gov)

Society of American Foresters- Find a Certified Professional (eforester.org)

References

Article adapted and paraphrased from:

Demers and Long, Selecting a Consulting Forester. Publication: SS-FOR-16 University of Florida-IFAS

Extension, EDIS

Alabama Board of Registered Foresters, Website-https://www.asbrf.alabama.gov/ Last Accessed

07/22/2022

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 20, 2022

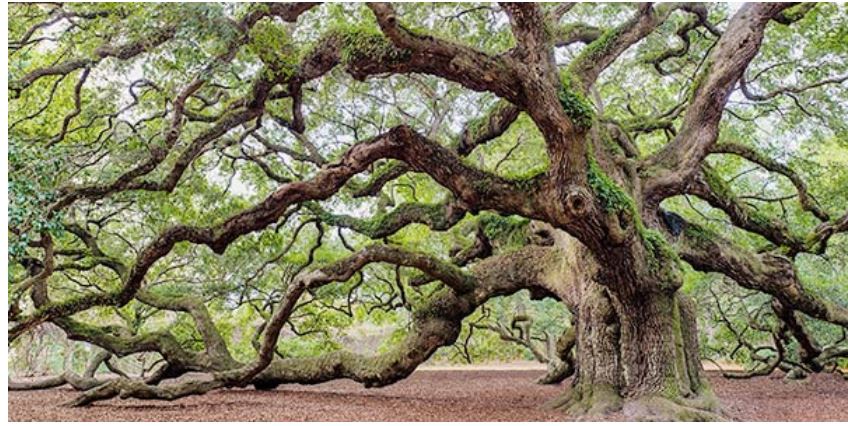

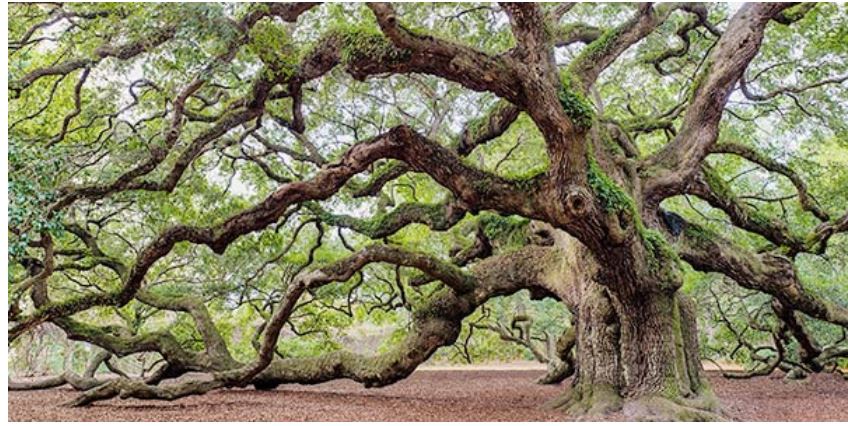

This giant heritage live oak tree has been providing oxygen, habitat, and shelter for 900 years! Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

While many people think of planting trees in the spring, autumn and winter are ideal for these activities in Florida. The cooler weather means most trees are no longer actively growing and producing new leaves and fruit, so there are fewer demands on a newly planted tree to start “working” right away. The dormant winter season allows the trees to acclimate to their new environment and begin developing sturdy root systems.

However, a newly planted tree is only as valuable as the care it’s given when planted. To ensure a successful tree, important steps to follow include proper placement, planting depth, mulching, and watering.

Proper tree planting practices can ensure a long-lived, healthy tree in the environment. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Before digging, look up and around to make sure there are no overhead or underground obstacles within the reaches of the tree’s mature height or root system. When digging the planting hole, make sure the hole is 2-3 times as wide as the root ball. When planted, the topmost root flare (where the roots join the trunk) should be just above the surface of the adjacent landscape. It is not necessary to fertilize a newly planted tree. Use mulch to retain moisture in the soil, but do not place it against the tree’s trunk. Finally, water the tree daily, saturating the root ball, for 1-2 weeks then weekly for a year.

For more information on planting trees and good varieties of trees for Florida, visit this excellent resource from UF. As always, one should strive to plant the right tree in the right place. For those who live in suburban or urban areas, considerations like tree size, leaf shed, and water requirements are big concerns. For more information on size evaluation and plant selection, please visit this link from the UF Horticulture department.

by Sheila Dunning | Jan 6, 2022

Old Live Oak

Picture from National Wildlife Foundation

The best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago. The second best time is Arbor Day. Florida recognizes the event on the third Friday in January, but planting any time before spring will establish a tree quickly.

Arbor Day is an annual observance that celebrates the role of trees in our lives and promotes tree planting and care. As a formal holiday, it was first observed on April 10, 1872 in the state of Nebraska. Today, every state and many countries join in the recognition of trees impact on people and the environment.

Trees are the longest living organisms on the planet and one of the earth’s greatest natural resources. They keep our air supply clean, reduce noise pollution, improve water quality, help prevent erosion, provide food and building materials, create shade, and help make our landscapes look beautiful. A single tree produces approximately 260 pounds of oxygen per year. That means two mature trees can supply enough oxygen annually to support a family of four.

The idea for Arbor Day in the U.S. began with Julius Sterling Morton. In 1854 he moved from Detroit to the area that is now the state of Nebraska. J. Sterling Morton was a journalist and nature lover who noticed that there were virtually no trees in Nebraska. He wrote and spoke about environmental stewardship and encouraged everyone to plant trees. Morton emphasized that trees were needed to act as windbreaks, to stabilize the soil, to provide shade, as well as fuel and building materials for the early pioneers to prosper in the developing state.

In 1872, The State Board of Agriculture accepted a resolution by J. Sterling Morton “to set aside one day to plant trees, both forest and fruit.” On April 10, 1872 one million trees were planted in Nebraska in honor of the first Arbor Day. Shortly after the 1872 observance, several other states passed legislation to observe Arbor Day. By 1920, 45 states and territories celebrated Arbor Day. Richard Nixon proclaimed the last Friday in April as National Arbor Day during his presidency in 1970.

Today, all 50 states in the U.S. have official Arbor Day, usually at a time of year that has the correct climatological conditions for planting trees. For Florida, the ideal tree planting time is January, so Florida’s Arbor Day is celebrated on the third Friday of the month. Similar events are observed throughout the world. In Israel it is the Tu B Shevat (New Year for Trees). Germany has Tag des Baumes. Japan and Korea celebrate an entire week in April. Even Iceland, one of the most treeless countries in the world observes Student’s Afforestation Day.

The trees planted on Arbor Day show a concern for future generations. The simple act of planting a tree represents a belief that the tree will grow and someday provide wood products, wildlife habitat, erosion control, shelter from wind and sun, beauty, and inspiration for ourselves and our children.

“It is well that you should celebrate your Arbor Day thoughtfully, for within your lifetime the nation’s need of trees will become serious. We of an older generation can get along with what we have, though with growing hardship; but in your full manhood and womanhood you will want what nature once so bountifully supplied and man so thoughtlessly destroyed; and because of that want you will reproach us, not for what we have used, but for what we have wasted.”

~Theodore Roosevelt, 1907 Arbor Day Message

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 14, 2021

A healthy and diverse native forest provides many benefits for environmental and human health. Photo credit, Cathy Hardin

Trees often are low on priority lists – unless you had tree damage as a result of Hurricane Sally. However, you might be surprised to learn that trees played a beneficial, if somewhat behind the scenes, role for good this year and every year. And celebrating the good, while not ignoring potential problems, is important when making decisions involving trees.

Often trees are disparaged, especially after a severe storm. Many trees fell during Sally, causing costly clean up and often significant damage. Some trees were damaged: causing hazardous conditions, opportunities for the tree disease and insect infestation, or simply aesthetically unpleasant disfigurement. Even without storms, trees require care, can interfere with utilities and foundations, and require extra clean up certain times of year. Yet, healthy well-maintained trees might reduce wind speeds and damage for property underneath or on the leeward (downwind) side of trees. Trees also significantly reduce erosion and absorb stormwater.

Bald cypress. Photo credit, Cathy Hardin

Trees often give more than they take. Many studies have been done on the effects of green space on a person’s well-being, including lowering blood pressure, speeding up recovery times, and lessening depression and anxiety. Other social benefits include lowering crime rates, increasing property values, creating beauty and space for recreation and relaxation, and lowering cooling bills. They provide habitat for birds and other wildlife. We haven’t even begun to mention the material benefits such as fruit, nuts, wood, and the 5,000 plus commercial products made from trees (wood, roots, leaves, and saps).

Author and county forester Cathy Hardin demonstrates proper tree planting at a past Arbor Day program. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

So, celebrate trees this year! Winter is a great time to improve existing trees and to plant new ones. Florida Arbor Day is celebrated the on the third Friday in January – January 15, 2021. National Arbor Day is the last Friday in April. In Escambia County, the UF IFAS Extension office is holding several Arbor Day related events, including a drive-through tree giveaway on January 23. Even if you are not able to attend a public event in your area, you still can get out and celebrate trees. Below are some ideas.

Existing Trees

• Care for storm damaged trees.

o Contact an arborist for evaluation of potential hazards

o Properly prune out broken limbs to create a smooth surface

o Some trees may not be able to be successfully treated and need removal

o Most trees will recover, but might need time and/or multiple treatments

• Learn about proper pruning techniques to take care of smaller trees yourself

• When hiring a professional is required, hire a reputable company with a certified arborist on staff. Ensure the company has both Personal and Property Damage Liability Insurance and Worker’s Compensation Insurance. Arborists certified by the International Society of Arboriculture can be found at http://www.isa-arbor.com/findanarborist/arboristsearch.aspx.

• Take care of tree roots. Don’t compact the soil by parking or piling things in the root zone. Use caution

when applying any chemicals (fertilizer, herbicide, pesticides) to the soil or lawn. Read the label to

ensure it will not harm your tree.

Florida yew. Photo credit, Cathy Hardin

New Plantings

• Decide what species of tree is right for you, considering the soil type, size of opening, climate, and eventual size of tree.

• Plant the tree at the right depth, not too deep or too shallow.

• Keep it simple. Soil amendments, fertilizers, and staking are usually unnecessary, especially for small native trees.

• Mulch lightly over the root zone, but not against the trunk.

• Water regularly until the tree is established. (Three gallons per inch of tree diameter weekly – applied slowly at the root ball)

• Celebrate!

• Take a photo of your favorite tree to post on social media. Tag the Florida Forest Service!

Longleaf pine. Photo credit, Cathy Hardin

• Take a hike in the woods or a nearby park.

• Have a picnic with friends or family by a tree.

• Be grateful for your tree and its benefits.

• Teach a child about trees. There are many activities that can be used. Check out Project Learning Tree Activities for Families – Project Learning Tree (plt.org) or the Arbor Day Foundation www.ArborDay.org for a few ideas.

• Plant a new tree.

For more information on the benefits of trees, visit healthytreeshealthylives.org or www.vibrantcitieslab.com. The Florida Forest Service, a division of the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, manages more than 1 million acres of state forests and provides forest management assistance on more than 17 million acres of private and community forests. The Florida Forest Service is also responsible for protecting homes, forestland and natural resources from the devastating effects wildfire on more than 26 million acres. Learn more at FDACS.gov/FLForestService.

Cathy Hardin is the Escambia County Forester for the Florida Forest Service and can be reached at Cathy.Hardin@fdacs.gov.

by Carrie Stevenson | Nov 18, 2020

A blackgum/tupelo tree begins changing colors in early fall. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

It’s autumn and images of red, brown, and yellow leaves falling on the forest floor near orange pumpkins enter our minds. However, Florida isn’t necessarily known for its vibrant fall foliage, but if you know where to look this time of year, you can find some amazing scenery. In late fall, the river swamps can yield beautiful fall leaf color. The shades are unique to species, too, so if you like learning to identify trees this is one of the best times of the year for it. Many of our riparian (river floodplain) areas are dominated by a handful of tree species that thrive in the moist soil of wetlands. Along freshwater creeks and rivers, these tend to be bald cypress, blackgum/tupelo, and red maple. Sweet bay magnolia (Magnolia virginiana) is also common, but its leaves stay green, with a silver-gray underside visible in the wind.

The classic “swamp tree” shape of a cypress tree is due to its buttressed trunk, an adaptation to living in wet soils. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) is one of the rare conifers that loses its leaves. In the fall, cypress tress will turn a bright rust color, dropping all their needles and leaving a skeletal, upright trunk. Blackgum/tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica) trees have nondescript, almost oval shaped leaves that will turn yellow, orange, red, and even deep purple, then slowly drop to the swamp floor. Blackgums and cypress trees share a characteristic adaptation to living in and near the water—wide, buttressed trunks. This classic “swamp” shape is a way for the trees to stabilize in the mucky, wet soil and moving water. Cypresses have the additional root support of “knees,” structures that grow from the roots and above the water to pull in oxygen and provide even more support.

A red maple leaf displaying its incredible fall colors. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

The queen of native Florida fall foliage, however, is the red maple (Acer rubrum) . Recognizable by its palm-shaped leaves and bright red stem in the growing season, its fall color is remarkable. A blazing bright red, sometimes fading to pink, orange, or streaked yellow, these trees can jump out of the landscape from miles away. A common tree throughout the Appalachian mount range, it thrives in the wetter soils of Florida swamps.

To see these colors, there are numerous beautiful hiking, paddling, and camping locations nearby, particularly throughout Blackwater State Forest and the recreation areas of Eglin Air Force Base. But even if you’re not a hiker, the next time you drive across a bridge spanning a local creek or river, look downstream. I guarantee you’ll be able to see these three tree species in all their fall glory.

by Daniel J. Leonard | Nov 18, 2020

The native Florida landscape definitely isn’t known for its fall foliage. But as you might have noticed, there is one species that reliably turns shades of red, orange, yellow and sometimes purple, it also unfortunately happens to be one of the most significant pest plant species in North America, the highly invasive Chinese Tallow or Popcorn Tree (Triadica sebifera).

Chinese Tallow fall foliage. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Native to temperate areas of China and introduced into the United States by Benjamin Franklin (yes, the Founding Father!) in 1776 for its seed oil potential and outstanding ornamental attributes, Chinese Tallow is indeed a pretty tree, possessing a tame smallish stature, attractive bark, excellent fall color and interesting white “popcorn” seeds. In addition, Chinese Tallow’s climate preferences make it right at home in the Panhandle and throughout the Southeast. It requires no fertilizer, is both drought and inundation tolerant, is both sun and shade tolerant, has no serious pests, produce seed preferred by wildlife (birds mostly) and is easy to propagate from seed (a mature

Chinese Tallow tree can produce up to 100,000 seeds annually!). While these characteristics indeed make it an awesome landscape plant and explain it being passed around by early American colonists, they are also the very reasons that make the species is one of the most dangerous invasives – it can take over any site, anywhere.

While Chinese Tallow can become established almost anywhere, it prefers wet, swampy areas and waste sites. In both settings, the species’ special adaptations allow it a competitive advantage over native species and enable it to eventually choke the native species out altogether.

In low-lying wetlands, Chinese Tallow’s ability to thrive in both extreme wet and droughty conditions enable it to grow more quickly than the native species that tend to flourish in either one period or the other. In river swamps, cypress domes and other hardwood dominated areas, Chinese Tallow’s unique ability to easily grow in the densely shaded understory allows it to reach into the canopy and establish a foothold where other native hardwoods cannot. It is not uncommon anymore to venture into mature swamps and cypress domes and see hundreds or thousands of Chinese Tallow seedlings taking over the forest understory and encroaching on larger native tree species. Finally, in waste areas, i.e. areas that have been recently harvested of trees, where a building used to be, or even an abandoned field, Chinese Tallow, with its quick germinating, precocious nature, rapidly takes over and then spreads into adjacent woodlots and natural areas.

Chinese tallow seedlings colonizing a “waste” area. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Hopefully, we’ve established that Chinese Tallow is a species that you don’t want on your property and has no place in either landscapes or natural areas. The question now is, how does one control Chinese Tallow?

- Prevention is obviously the first option. NEVER purposely plant Chinese Tallow and do not distribute the seed, even as decorations, as they are sometimes used.

- The second method is physical removal. Many folks don’t have a Chinese Tallow in their yard, but either their neighbors do, or the natural area next door does. In this situation, about the best one can do is continually pull up the seedlings once they sprout. If a larger specimen in present, cut it down as close to the ground as possible. This will make herbicide application and/or mowing easier.

- The best option in many cases is use of chemical herbicides. Both foliar (spraying green foliage on smaller saplings) and basal bark applications (applying a herbicide/oil mixture all the way around the bottom 15” of the trunk. Useful on larger trees or saplings in areas where it isn’t feasible to spray leaves) are effective. I’ve had good experiences with both methods. For small trees, foliar applications are highly effective and easy. But, if the tree is taller than an average person, use the basal bark method. It is also very effective and much less likely to have negative consequences like off-target herbicide drift and applicator exposure. Finally, when browsing the herbicide aisle garden centers and farm stores, look for products containing the active ingredient Triclopyr, the main chemical in brands like Garlon, Brushtox, and other “brush/tree & stump killers”. Mix at label rates for control.

Despite its attractiveness, Chinese Tallow is an insidious invader that has no place in either landscapes or natural areas. But with a little persistence and a quality control plan, you can rid your property of Chinese Tallow! For more information about invasive plant management and other agricultural topics, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office!

References:

Langeland, K.A, and S. F. Enloe. 2018. Natural Area Weeds: Chinese Tallow (Sapium sebiferum L.). Publication #SS-AGR-45. Printer friendly PDF version: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/AG/AG14800.pdf