by Rick O'Connor | Feb 18, 2022

I recently posted an article about the seahorses of the Florida panhandle. It would be remiss of me if I did not include their close cousins the pipefish. Where seahorses are well known but hard to find, pipefish are easy to find but not well known.

The seahorse-like pipefish.

Photo: University of Florida

Pipefish are in the same family as seahorses, Syngnathidae, and are basically elongated seahorses. Pulling seine nets in local grassbeds we often catch them. Students always ask what they are. “Are these needlefish?” is a frequent question. I reply “no, they are pipefish”. Which then comes “pikefish?”. To which I reply “No, PIPEfish… like P-I-P-E… – they are basically elongated seahorses”. And then there is always – “coool”. To which I reply “yes… very cool”.

Pipefish have the same body armor, body rings, and long tube snout of the seahorse. However, they lack the curled prehensile tail for a more elongated body, looking more a grass blade than their cousins. They actually have a caudal fin (the fin most call “fish tail”). Most range between 3-6 inches long but the chain pipefish can reach a length of 10 inches, this is the “big boy” of the group. Like seahorses, they hide in the grass using their tube-shaped mouths to suck in small planktonic food. Like the seahorses, the males’ possess a brood pouch to carry the fertilized eggs and give live birth (ovoviviparous).

The pipefish can quickly be divided into two groups – those with long snouts, and those with short – and this can be easily seen when captured in a net. After that identification gets a bit tricky, you have to count rays in the fins or rings on the body. It is sufficed to say, “it’s a pipefish” and leave it at that.

Those with long snouts include the Opossum, Chain, Dusky, and Sargassum pipefish.

The Opossum Pipefish (Microphis brachyurus) is about 3 inches long and was not reported from the northwestern Gulf of Mexico according to Hoese and Moore1. In the eastern Gulf, our way, it is considered rare but has been found in salt marshes, seagrasses, and in Sargassum mats drifting in from the Gulf. The Florida Museum of Natural History list this fish as a “marine invader”2. In 1991 NOAA listed it as a species of concern due to its decline across the region3. There are reports of this pipefish entering freshwater creeks within our estuaries.

The Chain Pipefish (Syngnathus louisianae) has a very long snout and is the “big boy” of the group reaching 10 inches in length. It is quite common along the panhandle and has one of the larger ranges of this group, found all along the Atlantic coast, throughout the Gulf of Mexico and in the Caribbean.

The Dusky Pipefish (Syngnathus floridae) is a long-snout, large pipefish reaching a length of eight inches. It prefers higher salinity than many pipefish and is found throughout the Gulf of Mexico and along the Atlantic seaboard often offshore.

The Sargassum Pipefish (Syngnathus pelagicus). This is a good scientific name for this fish (pelagicus) for it lives on the large mats of Sargassum weed that drifts across the oceans. Because of this it has a worldwide distribution. This longnose pipefish reaches the typical length of six inches. It lives as many other pipefish do hiding in the grass snapping up food when it comes close enough but it’s habitat is often drifting offshore and inshore sightings of this species are rare.

There are three species of “short-snout” pipefish.

The Fringed Pipefish (Anarchopterus crinigerus) is a smaller pipefish reaching only three inches. It seems to be absent in the western Gulf but is found along the Florida panhandle, the Gulf coast of peninsula Florida, and through the Caribbean to Brazil.

The Northern Pipefish (Syngnathus fuscus) reaches a length of six inches. It is very common along the Atlantic seaboard but Hoese and Moore1 report only four specimens from the Gulf of Mexico. This one would be considered very rare, and an expert should identify it if one thinks they have it.

The Gulf Pipefish (Syngnathus scovelli) is one of the more common pipefish collected in our waters. It is a short-snout species reaching the typical six inches but has these distinct bluish-gray bars that run vertically along the sides. It is found throughout the Gulf of Mexico and even into some freshwater habitats. The Florida Museum of Natural History also list this species as a marine invader4.

I am not sure how much seining you do along our waterways, but if you do any within the grassbeds you are sure to find one of these unique and interesting fish.

References

1 Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

2 Opossum pipefish. Discover Fishes. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/florida-fishes-gallery/opossum-pipefish/.

3 Opossum Pipefish. Species of Concern. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service. https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML1224/ML12240A312.pdf.

4 Gulf Pipefish. Discover Fishes. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/florida-fishes-gallery/gulf-pipefish/.

by Andrea Albertin | Jan 20, 2022

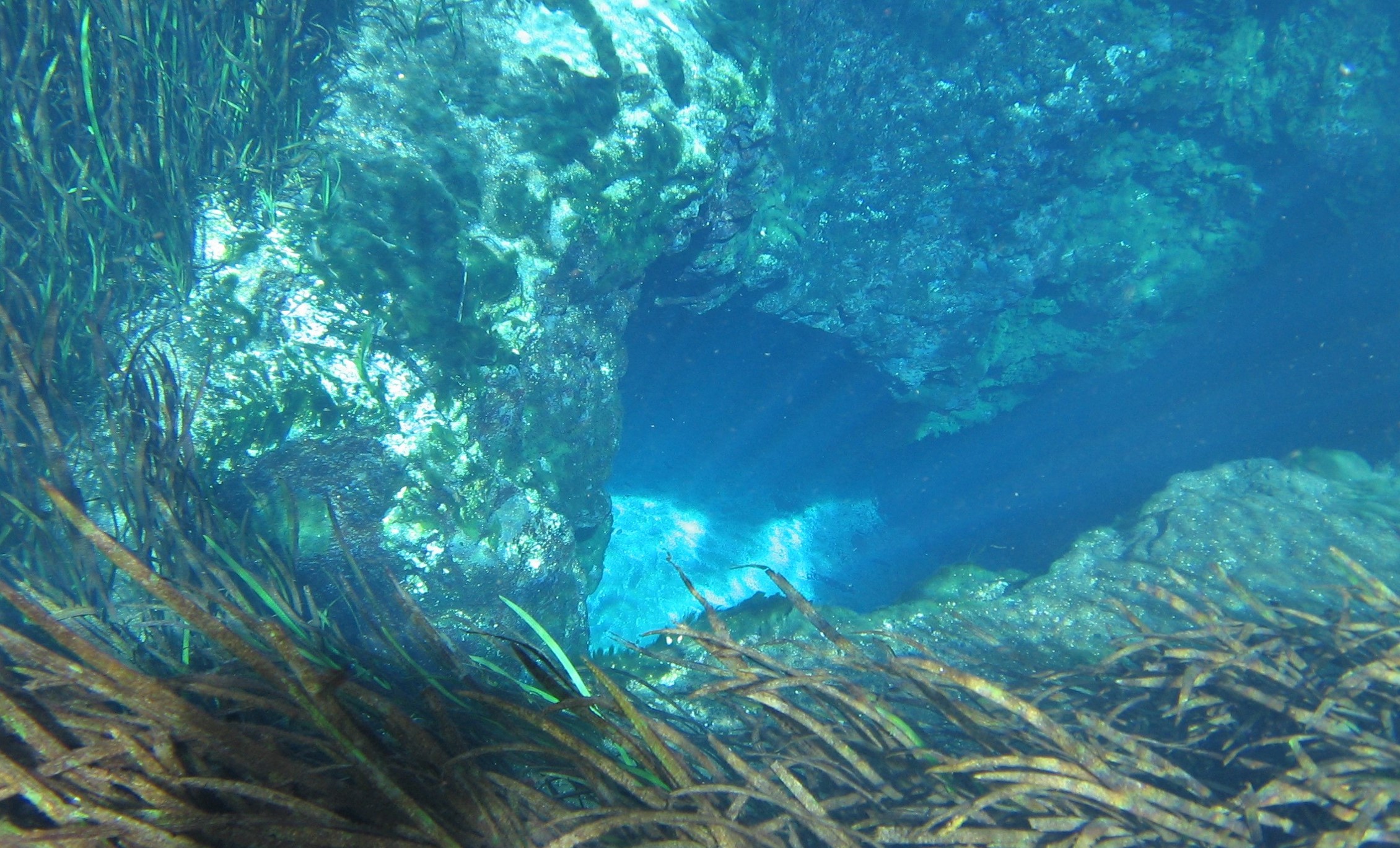

Jackson Blue Springs discharging from the Floridan Aquifer. Jackson County, FL. Image: Doug Mayo, UF/IFAS Extension.

Florida has one of the largest concentrations of freshwater springs in the world. More than 1000 have been identified statewide, and here in the Florida Panhandle, more than 250 have been found. Not only are they an important source of potable water, springs have enormous recreational and cultural value in our state. There is nothing like taking a cool swim in the crystal-clear waters of these unique, beautiful systems.

How do springs form?

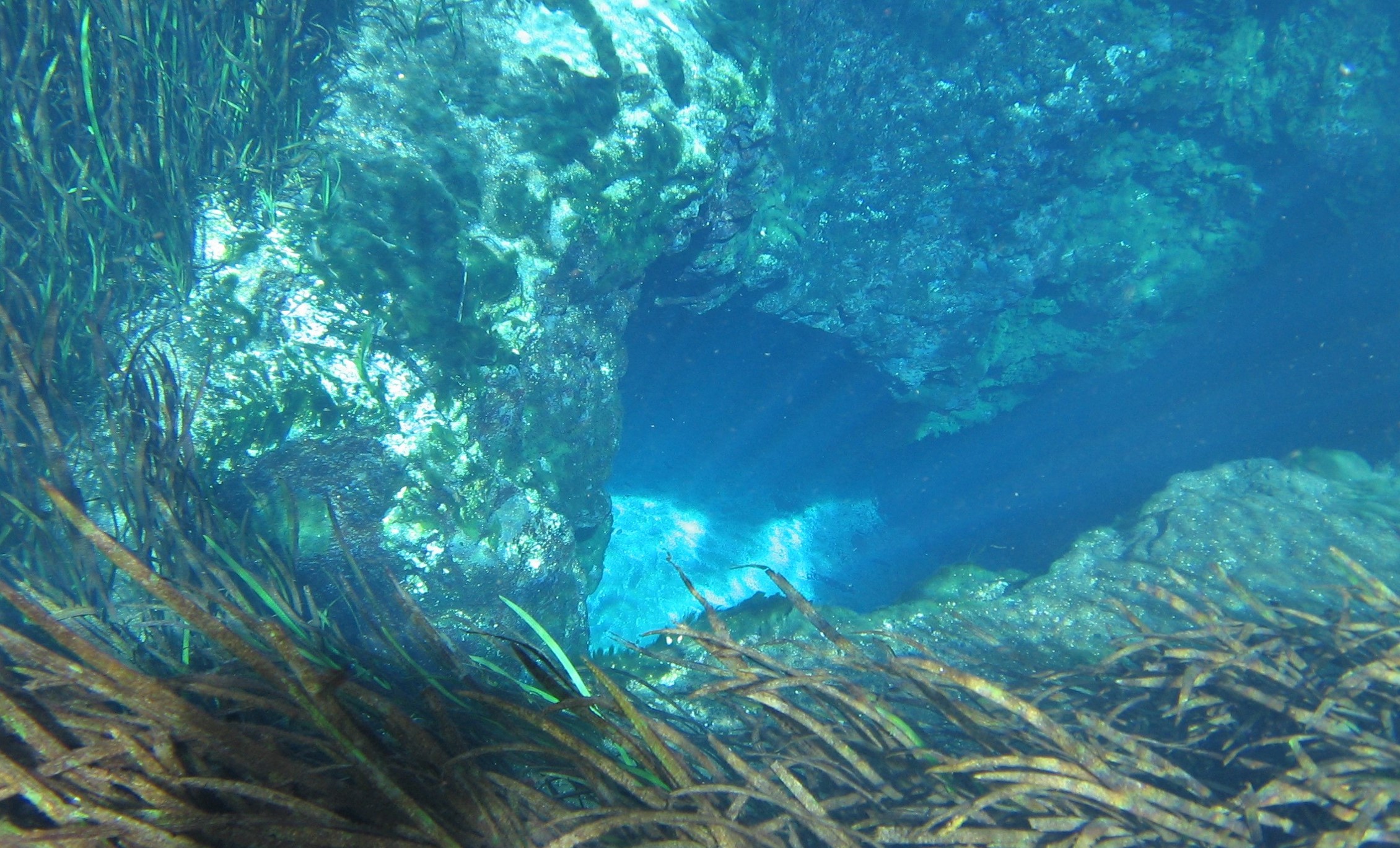

We have so many springs in Florida because of the state’s geology. Florida is underlain by thick layers of limestone (calcium carbonate) and dolomite (calcium magnesium carbonate) that are easily dissolved by rainwater that percolates into the ground. Rainwater is naturally slightly acidic (with a pH of about 5 to 5.6), and as it moves through the limestone and dolomite, it dissolves the rock and forms fissures, conduits, and caves that can store water. In areas where the limestone is close to the surface, sinkholes and springs are common. Springs form when groundwater that is under pressure flows out through natural openings in the ground. Most of our springs are found in North and North-Central Florida, where the limestone and dolomite are found closest to the surface.

Springs are windows to the Floridan Aquifer, which supplies most of Florida’s drinking water. Image: Ichetucknee Blue Hole, A. Albertin.

These thick layers of limestone and dolomite that are below us, with pores, fissures, conduits, and caves that store water, make up the Floridan Aquifer. The Floridan Aquifer includes all of Florida and parts of Georgia, South Carolina, and Alabama. The thickness of the aquifer varies widely, ranging from 250 ft. thick in parts of Georgia, to about 3,000 ft. thick in South Florida. The Floridan is one of the most productive aquifer systems in the world. It provides drinking water to about 11 million Floridians and is recharged by rainfall.

How are springs classified?

Springs are commonly classified by their discharge or flow rate, which is measured in cubic feet or cubic meters per second. First magnitude springs have a flow rate of 100 cubic feet or more per second, 2nd magnitude springs have a rate of 10-100 ft.3/sec., 3rd magnitude flows are 1-10 ft.3/sec. and so on. We have 33 first magnitude springs in the state, and the majority of these are found in state parks. These springs pump out massive amounts of water. A flow rate of 100 ft.3/sec. translates to 65 million gallons per day. Larger springs in Florida supply the base flow for many streams and rivers.

What affects spring flow?

Multiple factors can affect the amount of water that flows from springs. These include the amount of rainfall, size of caverns and conduits that the water is flowing through, water pressure in the aquifer, and the size of the spring’s recharge basin. A recharge basin is the land area that contributes water to the spring – surface water and rainwater that falls on this area can seep into the ground and end up as part of the spring’s discharge. Drought and activities such as groundwater withdrawals through pumping can reduce flow from springs systems.

If you haven’t experienced the beauty of a Florida Spring, there is really nothing quite like it. Here in the panhandle, springs such as Wakulla, Jackson Blue, Pitt, Williford, Morrison, Ponce de Leon, Vortex, and Cypress Springs are some of the areas that offer wonderful recreational opportunities. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection has a ‘springs finder’ web page with an interactive map that can help you locate these and many other springs throughout the state.

https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2020/04/09/the-incredible-floridan-aquifer/

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 17, 2021

This is another one of those fish in this series that is not often seen but when you do see one you will ask “what is that?” – So, we will answer the question by including it here.

Like the frogfish we have already written about, batfish are described by Hoese and Moore1 as “grotesque” and they take it a step further by telling us all “ugly” fish (as they say) are grouped into what many call “dogfish”. As with the frogfish, I am not sure I would use the term grotesque, but they are strange looking.

Juvenile Polka-Dot Batfish (Ogcocephalus radiatus) in the polluted intracoastal waterway in Palm Beach County, FL.

Photo: Science Photo Library

I have only seen a couple in my life. Hoese and Moore mention they are often brought up in shrimp trawls, and I have seen them while doing trawl surveys at Dauphin Island Sea Lab. I also found one while snorkeling along a seawall near Gulf Breeze FL. So, they are out there just not encountered as often, or as well known, or seen as frequently, as many other fish in the Gulf. Another reason to include this group here.

It is hard to describe what this fish looks like. They are, as they say, dorso-ventrally flattened – meaning from top to bottom, not side to side – like a stingray. They have two fins extending from parts of their body that sort of “stick out of the side” and appear to be like webbed feet with which they walk. Actually, there are these small, modified fins on the ventral side that are used to walk on the bottom – they are bottom dwelling (benthic) fish for sure. Like their relatives the frogfish they have a modified spine that is used like a fishing lure. Like the frogfish, the shape of that lure can be used to identify species. But unlike the frogfish the lure is located between their mouth (which near the bottom of the body and is very small) and a pointed rostrum that extends from the top of their head like a battering ram. This lure is extended to lure not fish swimming above, as with the frogfish, but small creatures in and on the sand. Because of this they do not call the lure an illicium but a esca. These are strange looking fish.

Hoese and Moore list four different species and indicate there are at least three others in the Gulf of Mexico. Most are associated with the continental shelf of the Gulf and not inland where we might see them snorkeling around. A couple of species are more associated the continental slope, which drops from the continental shelf to the deep sea. But the Polka-dot batfish (Ogocephalus cubifrons) is reported as being inshore and is the species I have encountered.

Many species are only described as being from the shelf of the Gulf of Mexico and no other oceans. Some of them are even more restricted to either the eastern or western Gulf. This all suggests that batfish do have biogeographic barriers of some sort restricting their dispersal. Being offshore benthic fish, your first guess would be substrate. Usually in those locations the temperature and salinities are pretty similar but the material on the bottom (rock, shell, sand, canyons, etc.) are not. However, several articles mention that batfish can be found over rocky or sandy bottom2,3,4 and the polka-dot batfish can be found in grassbeds as well2. So, I am not sure what the possible barrier is, but several do have a limited range. The east-west split could very well be the DeSoto Canyon off the coast of Pensacola.

All of that said, it is a very interesting group of fish that for one species you might encounter while out and about snorkeling or diving in the Florida panhandle.

References

1 Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station, TX. Pp. 327.

2 Ogocephalus cubifrons, Polka-dot batfish. 2017. Discover Fishes. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/ogcocephalus-cubifrons/.

3 The Red-lipped Batfish. 2014. Ashland Vertebrate Biology. Ashland University, Ohio. http://ashlandvertbio.blogspot.com/2014/12/the-red-lipped-batfish.html.

4 Cocos Batfish, Ogocephalus porrectus. 2015. Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. https://biogeodb.stri.si.edu/sftep/en/thefishes/species/777.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 2, 2021

This series on vertebrates of the Florida panhandle is to enhance your education of the different animals that call this place home. This is the only reason to include clingfish to this list… to enhance your education.

There are about 500 species of fishes in the northern Gulf of Mexico. We I began this series I had no intention of writing about all of them. I was going to focus on the more common and familiar, such as snappers and mackerels. Things like the clingfish were to be skipped over. But when I saw this family next on the list, I could not skip over this one. You see, this is actually a pretty common fish that you many have already encountered and followed by asking “what kind of fish is this?” So, we will include our friend the clingfish.

Clingfish

Photo: University of Washington

It belongs to the family Gobiesocidae and, in the northern Gulf of Mexico, there is only one resident species, Gobiesox strumosus, known as the clingfish or skilletfish. They are called this because their body shape resembles a cast iron skillet, roundish head with an extended tail and dark in color. The often-used clingfish name comes from the sucker apparatus they form on the ventral side of their body to cling to rocks and inside of shells – where they are most often found. Hoese and Moore1 report only one species from the northern Gulf but suggest there could be more on the offshore reefs.

The local skilletfish is reported to reach a mean length of three inches. I have only seen a few of these and the ones I found were smaller than this. They are dark in color, often with stripes or streaks, and can be all black – the ones I have found were all black. The ones I have found are inside dead oyster shells associated with oyster reefs. You may find a random oyster clump on the bottom. You just pick it up, look inside the opened shells and open the dead shells, and you may find one. They have been reported associated with rocks, pipes, and other structures on the bottom.

This species does have a large geographic range, suggesting few barriers to dispersal. They are found from New Jersey to Brazil and throughout the Gulf of Mexico.

There is no commercial value for the animal, no cool natural history facts, just an small fish that you may come across while playing in the Gulf that you might ask – “what kind of fish is this?” Now you know, it’s the clingfish.

Reference

1 Hoese, H. D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Northern Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Chris Verlinde | Nov 19, 2021

Photo: Chris Verlinde

Photo: Chris Verlinde

The diversity and natural beauty of the Escribano Point Wildlife Management area is breathtaking. These six square miles of conservation lands provides many types of outdoor recreation including: birdwatching, kayaking, camping, swimming, fishing and hiking. The bays, estuaries, river swamps and other coastal habitats are managed to preserve native plants and animals. Visit Escribano Point Wildlife Management Area (WMA) soon and discover this piece of old Florida.

The Escribano Point WMA is part of state-owned conservation lands that provide habitat for rare plants and animals and promote water quality in Blackwater Bay, East Bay and the Yellow River. The diverse habitats found in Escribano Point WMA provide home to many types of wildlife including, deer, turkey, Florida Black Bears, birds, reptiles amphibians and fish.

As part of the Florida Master Naturalist Program’s 20th Anniversary, a small but mighty group hit the water just as the air temperature broke 60 degrees on Saturday. We kayaked up Fundy Bayou and out to Fundy Cove located along the southeast side of Blackwater Bay in Santa Rosa County, Fl.

As part of the Florida Master Naturalist Program’s 20th Anniversary, a small but mighty group hit the water just as the air temperature broke 60 degrees on Saturday. We kayaked up Fundy Bayou and out to Fundy Cove located along the southeast side of Blackwater Bay in Santa Rosa County, Fl.

We traveled through freshwater and saltwater marshes, along scrubby flat woods, beach and mesic hammock habitats. Ospreys, a kingfisher, and red-headed woodpecker entertained the group. The air temperature warmed as we paddled. When we arrived at the junction of Fundy Creek and Blackwater Bay, Blackwater Bay was rough. We paddled to the campground for lunch and enjoyed the peaceful beauty around us.

Thanks to Kayak Dave, one member of the group checked an action on her bucket list to paddle again.

Escribano Point WMA is a treasure located in Santa Rosa County, FL., approximately 20 south of Milton, FL . Take some and visit for a day or two, there are 2 campgrounds located at this WMA. Enjoy!