by Rick O'Connor | Oct 21, 2021

Catfish…

There are a lot of fish found along the Florida panhandle that many are not aware of, but catfish are not one of them. Whether a saltwater angler who captures one of those slimy hardhead catfish to a lover of freshwater fried catfish – this is a creature most have encountered and are well aware of.

Growing up fishing along the Gulf of Mexico, the “catfish” was one of our nemesis. Slinging your cut-bait out on a line, if you were fishing near the bottom, you were likely to catch one of these. Reeling in a slimy barb-invested creature, they would swallow your bait well beyond the lip of their mouths and it would begin a long ordeal on how to de-hooked this bottom feeder that was too greasy to eat. Many surf fishermen would toss their bodies up on the beach with the idea that removing it would somehow reduce their population. Obviously, that plan did not work but ghost crabs will drag their carcasses over to their burrows where they would consume them and leave the head skull that gives this species of catfish it’s common name “hardhead” catfish, or “steelhead” catfish. This hard skull has bones whose shape remind you of Jesus being crucified and was sold in novelty stores as the “crucifix fish”.

The bones in the skull of the hardhead catfish resemble the crucifixion of Christ and are sold as “crucifix fish”.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

When I attended college in southeast Alabama a group of friends wanted to go out for fried catfish. I, knowing the above about saltwater catfish, replied “why?… no…, you don’t eat catfish”. They assured me you did and so off we went to a local restaurant who sold them. Fried catfish quickly became one of my favorites. A fried catfish sandwich with slaw and beans is something I always look forward to. At that time, I was not aware of the freshwater catfish, nor the catfish farms that produce much of the fish for my sandwiches. I now have also become aware of the method of catching freshwater catfish called “noodling” – which is not something I plan to take up.

Worldwide, there are 36 families and about 3000 species of what are called catfish1. Most are bottom feeders with flatten heads to burrow through the substrate gulping their prey instead of biting it. Most possess “whiskers” – called barbels, which are appendages that can detect chemicals in the environment (smell or taste) helping them to detect prey that is buried or hard to find in murky waters. These barbels resemble whiskers and give them their common name “catfish”.

The serrated spines and large barbels of the sea catfish. Image: Louisiana Sea Grant

They lack scales, giving them the slimy feel when removing them from your hook, and also have a reduced swim bladder causing them to sink in the water – thus they spend much of their time on the bottom. The mucous of their skin helps in absorbing dissolved oxygen through the skin allowing them to live in water where dissolved oxygen may be too low for other types of fish1.

They are also famous for their serrated spines. Usually found on the dorsal and pectoral fins, these spines can be quite painful if stepped on, or handled incorrectly. Some species can produce a venom introduced when these spines penetrate a potential predator which have put some folks in the hospital1.

The size range of catfish is large; from about five inches to almost six feet. In North America, the largest captured was a blue catfish (Ictalurus furcatus) at 130 pounds. The largest flathead catfish (Pylodictis olivaris) was 123 pounds. But the monster of this group is the Mekong catfish of southeast Asia weighing in at over 600 pounds.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission lists six species of catfish in the Florida panhandle area. However, they are focusing on species that people like to catch2.

The Blue Catfish

Photo: University of Florida

This large blue catfish is being weighed by FWC researchers. Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

The Channel Catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) is found throughout Florida and also in many river systems of the eastern United States. It has found few barriers dispersing through these river systems. They are not typically bottom feeders having a more carnivorous diet.

The Flathead Catfish (Pylodictis olivaris) are relatively new to Florida and are currently reported in the Escambia and Apalachicola rivers. They prefer these slow-moving alluvial rivers.

The Blue Catfish (Ictalurus furcatus) were first reported in the Escambia and Yellow Rivers, there are now records of them in the Apalachicola. These catfish prefer faster moving rivers with sand/gravel bottoms and seem to concentrate towards the lower ends of major tributaries.

The White Catfish (Amerius catus) is found in rivers and streams statewide, and even in some brackish systems.

The Yellow Bullhead (Amerius natalis) are most often found in slow moving heavily vegetated systems like ponds, lakes, and reservoirs. It is reported to be more tolerant of poor water conditions.

The Brown Bullhead (Amerius nebulosus) live in similar conditions to the Yellow Bullhead.

The dispersal of freshwater catfish is interesting. How do they get from the Escambia to the Apalachicola Rivers without swimming into the Gulf and up new rivers? The answer most probably comes from small tributaries further upstream that can, eventually, connect them to a new river system. Scientists know that eggs deposited on the bottom can be moved by birds who feed in each of the systems carrying the eggs with them as they do. And you cannot rule out movement by humans, whether intentionally or accidentally.

On the saltwater side of things, there are two species – though the blue catfish has been reported in the upper portions of some estuaries in low salinities in the western Gulf of Mexico. The marine species are the hardhead catfish (Arius felis), sometimes known as the “steelhead” or the “sea catfish” – and the gafftop (Bagre marinus), also known as the gafftopsail catfish3.

The hardhead catfish is very familiar with anglers along the Gulf coast. This is the one I was referring to at the beginning of this article. It is considered inedible and a nuisance by most. They are common in estuaries and the shallow portions of the open sea from Massachusetts to Mexico. They are reported to have an average length of two feet, though most I have captured are smaller. Like many catfish, they possess serrated spines on their dorsal and pectoral fins. Their distribution seems to be limited by salinity.

The gafftop is also reported to have a mean length of two feet, and most that I have captured are closer to that. At one point in time, we were longlining for juvenile sharks in Pensacola Bay and caught numerous of these thinking they were small bull sharks as we pulled the lines in, until we saw the long barbels extending from them. I remember this being a very slimy fish, covered with mucous, and not fun to take off the hooks. It is reported to have good food value, though I have not eaten one. They differ from the hardheads mainly in their extended rays from the dorsal and pectoral fins. The habitat and range are similar to hardheads, though they have been reported as far south as Panama.

The extended rays of the gafftop catfish.

Photo: University of Florida.

The diversity of freshwater catfish in the U.S. goes beyond what has been reported here. This group has been found on most continents and have been very successful. There are plenty of local catfish farms where you can try your luck, have them cleaned, and enjoy a good meal.

References

1 Catfish. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catfish.

2 Catfish. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. https://myfwc.com/fishing/freshwater/sites-forecasts/catfish/.

3 Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 23, 2021

These are all fish that many have heard of but know nothing about. They are not even sure what they look like. We have heard of them as a seafood product. Smoked herring, canned sardines, and anchovy pizza are popular the world over. These are one of the largest commercial species harvested in U.S. waters. In 2020 over 6 million pounds of sardines, 12 million pounds of anchovies, 41 million pounds of herring, 1.3 BILLION pounds of menhaden were harvested. The menhaden catch alone was valued at just under $200 million2. It not as large a fishery in Florida. 327,000 pounds of menhaden, 700,000 pounds of sardines, and 1.8 million pounds of herring were harvested from state waters in 2020 and at value of about $900,000 in 2020. The fish are popular in many European dishes, cat food, and menhaden oil is used in many products.

The Gulf menhaden supports a large commercial fishery in the Gulf of Mexico.

Photo: NOAA

These fishes are actually divided into two families. The herring, sardine, and menhaden are in the Family Clupeidae and are often called “clupeids”. This family includes 11 species in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Most have a “hatchet” shape to their bodies – being straight along their back with a deep curve along the ventral side, and most having a forked, or lunate, tail. They average between 2-20 inches in length and form massive schools as they travel near the surface waters filtering plankton. They are often harvested using purse seines. Large factory vessels will plow the waters searching for the large schools. Often, they will use aerial assistance to search such as small airplanes or ultralights. Once spotted, small chase boats will be launched from the factory vessel hauling the large purse seine around the school. Once that is completed a large weight called a “tommy” is dropped that “zips” the purse shut and captures the fish. There is little bycatch in this method.

Purse seining in the Pacific Ocean.

Photo: NOAA

The anchovies are found in the family Engraulidae. They differ in that they are more streamlined in shape and their mouths are larger / body size than the clupeids. Though there is no commercial fishery for them in Florida, they comprise one of the largest groups of schooling fish in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Hoese and Moore mention that the local species are too small for a fishery. The five native species average between 2.5-5.5 inches in length1. Some marine biologists consider anchovies as an “environmental canary”, or indicator species. Their presence can suggest good water quality. I have often caught them in seines along the beach in the Pensacola area. They resemble the very common silverside minnow in that they have a silver stripe running down their sides. But they differ in that they (a) only have a single dorsal fin (silversides have two), and (b) their snouts extend to a point resembling the head of a shark.

This striped anchovy resembles a silver side but differs with the shape of its snout and the number of dorsal fins.

Photo: NOAA

The distribution and biogeography of this group of fishes is all over the place. The round herring (Etrumeus teres) has few barriers and is found from the Bay of Fundy (at the Canadian/Maine border) to the Pacific Ocean1! A few species have the classic “Carolina” distribution – meaning they are found from North Carolina south, the entire Gulf of Mexico, and down to Brazil. For whatever reason (currents, water temperature, other) they do not venture north of the Carolinas and are probably impacted by the large amount of freshwater entering the Atlantic Ocean near the Amazon River.

Twp species are restricted by tropical conditions. The tiny dwarf herring (Jenkinsia lamprotaenia) and the Spanish sardine (Sardinella anchovia) are both listed as being restricted by water temperatures, though I have captured plenty of the Spanish sardines in the Pensacola area.

Some species are restricted to either the eastern or western Gulf of Mexico. Usually, the barrier for this distribution is the Mississippi River. Like the Amazon, there is a large plume of highly turbid/low salinity water extending into the Gulf of Mexico which keeps some species from crossing. Hoese and Moore report the Alabama shad (Alosa alabamae) only from the area between the Mississippi River and the Florida panhandle. The Mississippi River to one side, and the Apalachicola on the other.

Clupeids, like this Pacific sardine, for m large schools can consist of literally millions of fish.

Photo: NOAA

And finally, there is a spatial distribution with some species between freshwater, estuaries, and the open shelf. Two species, the threadfin shad (Dorosoma petenense) and the gizzard shad (Dorosoma cepedianum) are more associated with freshwater. The scaled sardine (Harengula pensacolae) is more common on the open shelf of the Gulf.

We all know the names of these fish but are unaware of their general biology and importance to commercial fisheries around the world. Many are common in our estuaries and play an important role in the health of the overall ecology. They are important members of the “panhandle fish family”.

References

1 Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

2 NOAA Fisheries. 2021. Commercial Landings. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/foss/f?p=215:200:2082956461436::NO:::.

3 Florida Commercial Landings. 2021. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. https://myfwc.com/research/saltwater/fishstats/commercial-fisheries/landings-in-florida/.

by Laura Tiu | Sep 9, 2021

A Lionfish Removal and Awareness Day festival volunteer sorts lionfish for weighing. (L. Tiu)

The northwest Florida area has been identified as having the highest concentration of invasive lionfish in the world. Lionfish pose a significant threat to our native wildlife and habitat with spearfishing the primary means of control. Lionfish tournaments are one way to increase harvest of these invaders and help keep populations down. Not only that, but lionfish are a delicious tasting fish and tournaments help supply the local seafood markets with this unique offering.

Since 2019, Destin, Florida has been the site of the Emerald Coast Open (ECO), the largest lionfish tournament in the world, hosted by Destin-Fort Walton Beach and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission (FWC). While the tournament was canceled in 2020, due to the pandemic, the 2021 tournament and the Lionfish Removal and Awareness Day festival returned to the Destin Harbor May 14-16 with over 145 tournament participants from around Florida, the US, and even Canada. The windy weekend facilitated some sporty conditions keeping boats and teams from maximizing their time on the water, but ultimately 2,505 lionfish were removed during the pre-tournament and 7,745 lionfish were removed during the two-day event for a total of 10,250 invasive lionfish removed. Florida Sea Grant and FWC recruited over 50 volunteers from organizations such as Reef Environmental Education Foundation, Navarre Beach Marine Science Station and Tampa Bay Watch Discovery Center to man the tournament and surrounding festival.

Lionfish hunters competed for over $48,000 in cash prizes and $25,000 in gear prizes. Florida Man, a Destin-based dive charter on the DreadKnot, won $10,000 for harvesting the most lionfish, 1,371, in 2 days. Team Bottom Time secured the largest lionfish prize of $5,000 with a 17.32 inch fish. Team Into the Clouds wrapped up the $5,000 prize for smallest lionfish with a 1.61 inch fish, the smallest lionfish caught in Emerald Coast Open History.

It is never too early to start preparing for the 2022 tournament. For more information, visit EmeraldCoastOpen.com or Facebook.com/EmeraldCoastOpen. For information about Lionfish Removal and Awareness Day, visit FWCReefRangers.com

“An Equal Opportunity Institution”

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 2, 2021

Eels… when that name comes up most think of either the vicious moray eels or the famous electric eel. Moray eels do exist in the Florida panhandle, and we will talk about them. Electric eels do not, they are found in the Amazon River system. That said, we do have eels here – quite a few. There are at least 18 species found in six different families. Most are 2-3 feet in length, though the Banded Shrimp Eel (Ophichthus) can reach six feet. About half of them are found offshore on the middle and outer shelves, the other half can be found in the inner shelf and estuaries, a few species swim into freshwater. Shrimpers often catch them when trawling and occasionally anglers will catch them with rod and reel.

Eels superficially resemble snakes and sometimes are confused with them. I have been told more than once that we do have sea snakes here. We do not. What people are finding are one of the 18 species of eels in the area. We do have snakes swimming across our estuaries, but we do not have sea snakes.

Eels differ from snakes primarily in that they, being fish, possess gills – not lungs. Most eels do have sharp teeth, the morays are famous for theirs, but no eels are venomous – so no worries there. Most of our eels have very small scales or are completely scaleless and are often very slimy and difficult to handle. They have been used as bait and one species, the American eel (Anguilla rostrata), has been used for food.

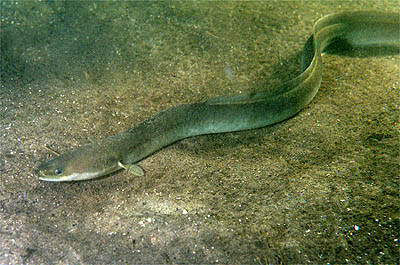

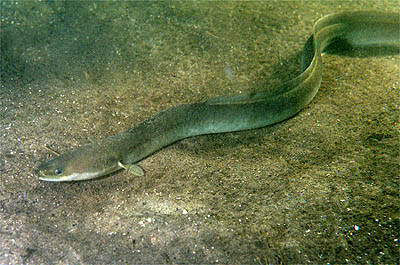

The Anguilla eel, also known as the “American” and “European” eel.

Photo: Wikipedia.

The American eel has an interesting life history. They spawn in the Sargasso Sea, an area in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. Their developing leptocephalus larva are thin, flat, and transparent in the water. They drift with the ocean currents into the Gulf of Mexico and eventually into our estuaries. I have found them along the shores of Project Greenshores (in Pensacola Bay) during certain parts of the year. From here they work their ways into our local rivers where people encounter the large adults. I have found them living in submerged caves near Marianna and many locals have found them at the bottom of our rivers. When time to breed, the adults will leave and head back to the open Atlantic to begin the cycle again. An amazing trip.

Moray eel.

Photo: NOAA

Moray eels are famous for the nasty attitudes and vicious bites. They are more tropical and associated with offshore reefs, though the ocellated moray (Gymnothorax ocellatus) is often caught in shrimp trawls. They live in the crevices of the reef ambushing prey. Some, like the green moray, can get quite large – over six feet. Like all eels, they have very powerful muscles and sharp teeth.

The shrimp eel is common on our inner and middle continental shelf.

Photo: NOAA

Conger eels are very common despite few people ever seeing them. There are six species and they frequent the middle continental shelf, so are rare in estuaries.

There are eight species of snake, or worm, eels. These are more common on the inner shelf and the coastal estuaries. Many prefer muddy bottoms where they bury tail first to ambush prey swimming by.

The majority of these marine eels have a large geographic distribution. Their larva can be carried great distances in the currents and their need for sandy or muddy bottoms can be met just about anywhere. They appear to have few barriers keeping them from colonizing much of the Gulf and surrounding waters. Most fall into the category we call “Carolina Fish”. Meaning their distribution occurs from the Carolinas, throughout the Gulf of Mexico, south to Brazil. There are a few species that can tolerate the lower salinities of the estuaries and one, the Anguilla eel, that can even venture into freshwater.

There are few species restricted to the tropical reefs, such as the morays. But morays are found on our smaller middle shelf and artificial reefs in the northern Gulf. Though found in parts of the Atlantic Ocean, Hoese and Moore1 reported one species of conger eel, Uroconger syringus, as only occurring near south Texas in the Gulf of Mexico. What barriers keep it from colonizing other Gulf habitats is unknown.

Eels are true fish that we rarely encounter. Encounters are usually startling but exciting at the same time. They are pretty amazing fish.

Reference

Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M University Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Erik Lovestrand | Aug 27, 2021

It seems like there has always been a soft spot in my heart for snakes. From a young age, I was fascinated with all reptiles. The rural fabric of where I grew up in Central Florida (think late-1960s) afforded many opportunities for us kids to roam the woods and fields in search of adventure during summer vacation. I vividly remember the occasional eastern hognose snake that we would catch as kids. They were easy to house for a while, as there was no shortage of toads for a food source. This article will focus on some of the common species of snakes in NW Florida and a couple of snake safety tips.

Very likely, one of the first species of snakes most people encounter in North Florida is the gray rat snake (aka oak snake). If you raise chickens, you can greatly reduce the time it takes to enjoy your first encounter. I pull oak snakes out of our nest boxes on a regular basis. I have also encountered some rather large pine snakes in this manner; one with eight egg lumps in its mid-section. These are both harmless, beautiful creatures that can unfortunately make you hurt yourself in a dimly lit coop as you reach in to collect eggs. Another commonly encountered snake in our area is the corn snake, also called a red rat snake. The orange background and dark-red blotches make this one of our most beautiful species. Southern black racers are also a commonly seen species due to their daytime hunting habits. Racers are black on the back with a white chin and very slender for their length. They live up to their name and can disappear in a flash when startled. Two other species regularly encountered here are in the “garter snake” group. The eastern garter snake is one of very few species in our area with longitudinal stripes. They can have a tan to yellowish background color or even a greenish or blue color. The closely related ribbon snake looks similar in color and pattern but has a much slimmer build.

Gray rat snakes are also called oak snakes and are quite common in North Florida

My home county of Wakulla is home to four species of venomous snakes, which include the eastern diamondback rattlesnake, pygmy rattlesnake, coral snake and Florida cottonmouth. However, if you live in other parts of North Florida, you may have five or possibly even six species that are venomous. The copperhead’s range extends into North Florida in a few Counties along the Apalachicola River and the canebrake (or timber) rattlesnake ranges slightly farther south in the peninsula to North-Central Florida. I’ve only seen one canebrake rattlesnake and it was crossing a road on the north side of Gainesville many years ago. Both pygmy rattlers and cottonmouths can be very abundant locally in the right habitats but diamondbacks and coral snakes are less common these days having lost much of their preferred habitats to development.

My best advice for those worried about being bitten by a snake is don’t try to pick one up, and watch where you put your hands and feet. It really is relatively easy to avoid (key word here is avoid) being bitten by a snake. There are many good medical sites on the web with detailed recommendations for snakebite treatment. In the very rare circumstance when someone is envenomated, the best policy is to remain as calm as possible and head for medical attention. Do not cut the skin and try to suck out the venom or apply a tourniquet. These strategies generally cause more harm than good.

I always appreciate the chance to get a look at one of our incredible native snakes when afield, especially if it happens to be one of our venomous species. A big diamondback rattlesnake is an impressive animal to happen on when afield. This appreciation does not mean that I don’t get startled occasionally when surprised, but once that instinctive reaction passes, I can truly appreciate the beauty of these scaly critters.