by Rick O'Connor | Jan 27, 2022

Members of the family Poeciliidae are what many call “livebearers”. Live bearing meaning they do lay eggs as most fish do, but rather give birth to live young. But this is not to be confused with live-bearing you find in mammals – which is different.

Most fish lay eggs. The females and males typically have a courtship ritual that ends with the female’s eggs (roe) being laid on some substrate, or released into the water column, and the male’s sperm (milt) are released over them. Once fertilized the gelatinous covered eggs begin to develop.

Everything the developing young need to survive is provide within the egg. The embryo is suspended in a semi-gelatinous fluid called the amnion. Oxygen and carbon dioxide gas exchange occurs through this amnion and through the gelatinous covering of the egg itself. Food is provided in the form of yolk, which is found in a sac attached to the embryo. There is a second sac, the allantois, where waste is deposited. When the yolk is low and the allantois full – it is time to hatch. This usually occurs in just a few days and often the baby fish (fry) are born with the yolk sac still attached. Parental care is rare, they are usually on their own.

With “livebearers” in the family Poecillidae it is different.

The males have a modified anal fin called a gonopodium. They fertilize the roe not externally but rather internally – more like mammals. The fertilized eggs develop the same as those of other fish. There is a yolk sac and allantois, and the embryo is covered in amnion within the gelatinous egg covering. But these eggs are held WITHIN the female, not laid on the substrate or released into the water column. When they hatch the live fry swim from the mother into the bright new world – hence the term “livebearer”.

There are advantages to this method. The eggs are protected inside the mother, and she obviously provides parental care to her offspring. However, this does make her much slower and an easier target for predators. There is some give and take.

This differs from the “live-bearing” of most mammals in that there is still an egg. Mammals do still have a yolk sac but feeding and removing waste is done THROUGH THE MOTHER. Meaning the embryo is attached to the mother via an umbilical cord where the mother provides food and removes waste trough her placenta. There is no classic egg in this case. I say most mammals because there are two who live in Australia that still do lay eggs – the platypus and the spiny anteater, and the marsupials (kangaroos and opossums) are a little different as well – but marsupials do no lay eggs.

Biologists have terms for these. Oviparous are vertebrates that lay eggs – such as fish, frogs, turtles, and birds. Ovoviviparous are vertebrates that produce eggs but keep them within the mother where they hatch – such as some sharks, some snakes, and the live bearing fish we are talking about here. Then there are the viviparous vertebrates that do not have an egg but rather the embryo is attached, and fed by, the mother herself – like most mammals.

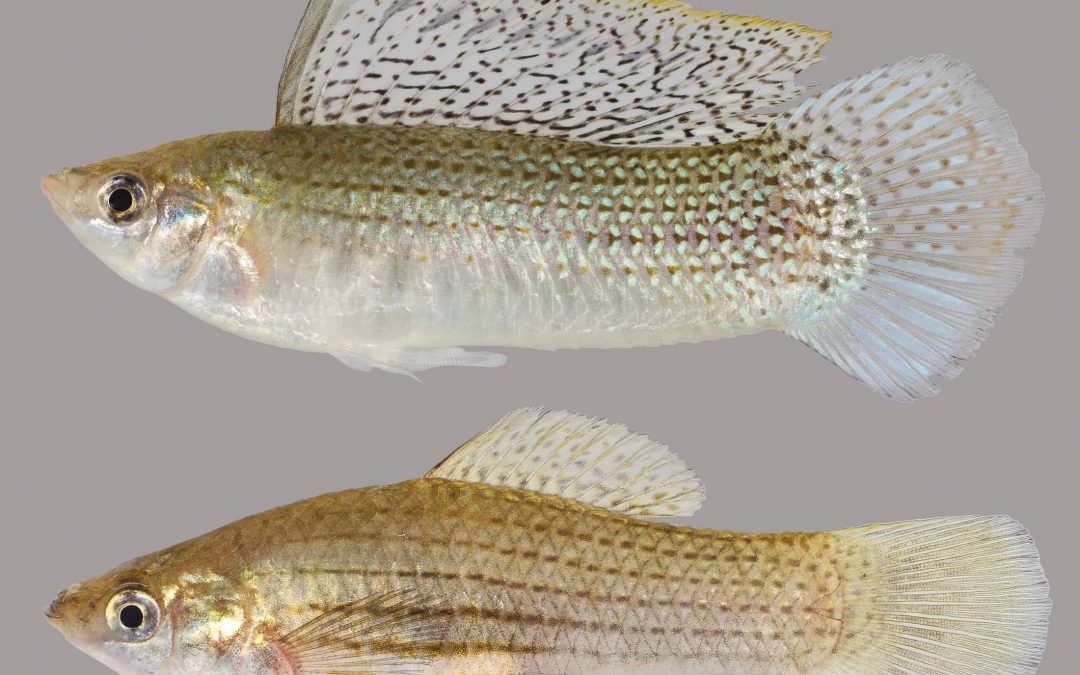

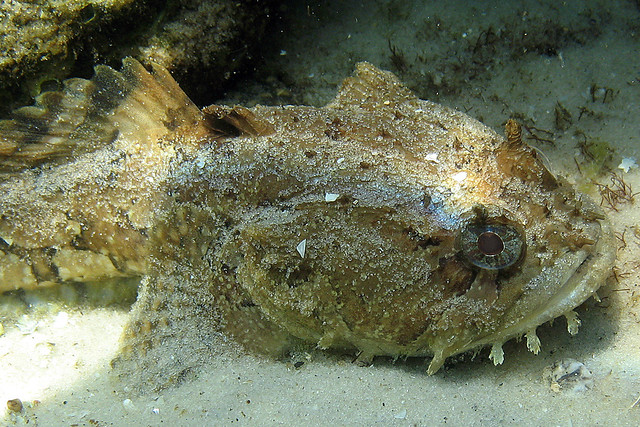

Sailfin Molly. The male is the fish above with the large “sailfin”. Note the gonopodium on his ventral side.

Photo: University of Florida

The livebearers of the family Poeciliidae are ovoviviparous. They are primarily small freshwater fish that are very popular in the aquarium trade. But there are two species that can tolerate saltwater and enter the estuaries of the northern Gulf of Mexico: the sailfin molly and the mosquitofish.

The Sailfin Molly (Poecilia latipinna) is the same fish sold in aquarium stores as the black molly. The black phase is quite common in freshwater habitats, but in the estuarine marshes the fish is more of a gray color with lateral stripes that is made up of a series of dots. They are short-stout bodied fish and the males possess the large sail-like dorsal fin from which the species gets its common name. The females resemble the males albeit no large sailfin and most found are usually round and full of developing eggs. They are very common in local salt marshes and often found in isolated pools within these habitats. The biogeographic range of this species is restricted to the southern United States, reported from South Carolina throughout the Gulf of Mexico. One would guess temperature may be a barrier to their dispersal further north along the Atlantic seaboard.

The mosquitofish.

Photo: University of Florida

The Mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) is familiar to many people whether they know it or not. Those who know the fish know they are famous for the habit of consuming mosquito larva and some, including our county mosquito control unit, use them to control these unwanted flying insects. For those who may they are not familiar with it, this is the fish frequently seen in roadside ditches, ephemeral ponds that show up after rainstorms, retention ponds, and other scattered bodies of freshwater within the community. Most who see them call them “minnows”. There is always the question as to “where did they come from?” You have a vacant lot – it rains one day – these small fish show up – where did they come from? The same can be said for community retention ponds. The county comes in a digs a hole – it rains one day, and the retention pond fills – and there are fish in it. One explanation to their source is the movement of fish by wading birds, where the fish incidentally become attached to their feet. Again, they are often released intentionally to help control local mosquito populations. This fish is found in our coastal estuaries but does not seem to like saltwater as well as the sailfin molly. It is found in cooler water ranging throughout the Gulf and as far north as New Jersey.

Both of these fish make excellent aquarium pets, and the sailfin molly in particular can be beautiful to watch.

Reference

Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 2, 2021

This series on vertebrates of the Florida panhandle is to enhance your education of the different animals that call this place home. This is the only reason to include clingfish to this list… to enhance your education.

There are about 500 species of fishes in the northern Gulf of Mexico. We I began this series I had no intention of writing about all of them. I was going to focus on the more common and familiar, such as snappers and mackerels. Things like the clingfish were to be skipped over. But when I saw this family next on the list, I could not skip over this one. You see, this is actually a pretty common fish that you many have already encountered and followed by asking “what kind of fish is this?” So, we will include our friend the clingfish.

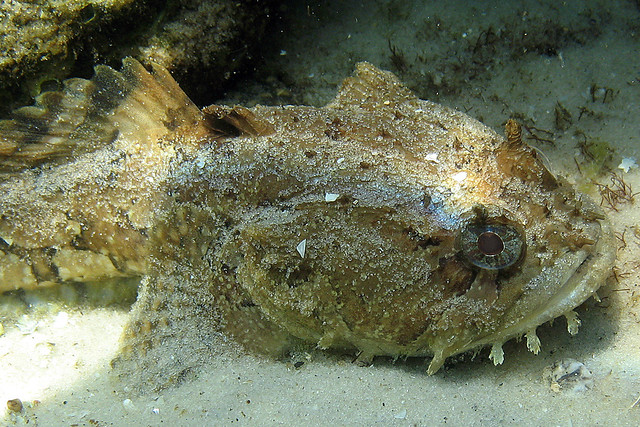

Clingfish

Photo: University of Washington

It belongs to the family Gobiesocidae and, in the northern Gulf of Mexico, there is only one resident species, Gobiesox strumosus, known as the clingfish or skilletfish. They are called this because their body shape resembles a cast iron skillet, roundish head with an extended tail and dark in color. The often-used clingfish name comes from the sucker apparatus they form on the ventral side of their body to cling to rocks and inside of shells – where they are most often found. Hoese and Moore1 report only one species from the northern Gulf but suggest there could be more on the offshore reefs.

The local skilletfish is reported to reach a mean length of three inches. I have only seen a few of these and the ones I found were smaller than this. They are dark in color, often with stripes or streaks, and can be all black – the ones I have found were all black. The ones I have found are inside dead oyster shells associated with oyster reefs. You may find a random oyster clump on the bottom. You just pick it up, look inside the opened shells and open the dead shells, and you may find one. They have been reported associated with rocks, pipes, and other structures on the bottom.

This species does have a large geographic range, suggesting few barriers to dispersal. They are found from New Jersey to Brazil and throughout the Gulf of Mexico.

There is no commercial value for the animal, no cool natural history facts, just an small fish that you may come across while playing in the Gulf that you might ask – “what kind of fish is this?” Now you know, it’s the clingfish.

Reference

1 Hoese, H. D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Northern Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 4, 2021

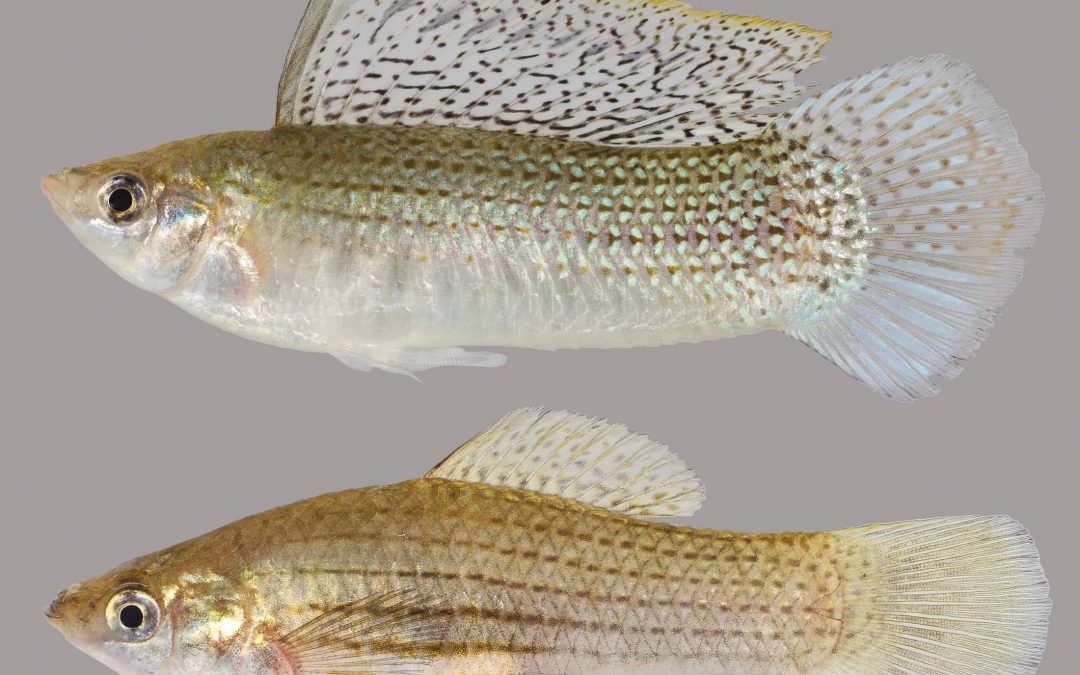

This is a group of fish that few have heard of and many have not seen – or if they saw them, had NO idea what they were – but they a very common in our local waters… the toadfish.

Once you see one, you will know why they call it this. Recently we had a matching game set up for the public to try and match the name of a common seagrass animal with its photograph. The toadfish was one of 20 species on the board. Few knew what it was and most only matched it with the photo through a process of elimination. A common response was “well… this MUST be the toadfish”, though there were just as many who did not see the connection between the name and the look on this fish’s face.

All that said, they are very common here. Snorkeling in our bays I have found them hiding in burrows within the grassbeds, snug against a seawall, and in open spaces within a rock jetty. They are known to hide inside discarded cans and bottles, feeding and eventually growing to large to be able to leave!

They are known for their painful bites; I have personally experienced this. We have captured them when seining the grassbeds. Trying to remove them from the net they are very slimy and difficult to grab. If you get close to their mouth, they will use the teeth they have. Others have been bitten when exploring the inside of a can or bottle left on the bottom. Toadfish belong to the family Batrachoididae and some members of this family are highly venomous. However, of the three species found in the northern Gulf, only the midshipman (Porichthys porosissimus) possess venom, and it is not harmful to humans.

I guess in a word you could say these are ugly fish – hence their name. They are all benthic and remain on the bottom at all times. Most of the swimming they do is to a new hiding place, where they ambush their prey. There are three species found in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

The Atlantic Midshipman

Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

The Atlantic Midshipman (Porichthys porosissimus) is a light tan colored fish with dark brown blotches along its side. Because of their light color, they are more common on light colored sand. The ones I have found are on the nearshore bottom of the Gulf side of our barrier island. They posses rows of photophores, cells that can produce light, and these rows of photophores resemble the rows of bright buttons on the 19th century midshipman’s naval uniform – hence their name. This fish has a mean length of eight inches. The midshipman has a more extensive range than the typical “Carolina” Gulf fish. They can be found from Virginia all the way to Argentina; beyond the Brazil limit most “Carolina” fish have. Though not reported on the other side of the Atlantic, nor the Pacific, this species seems to have few barriers impeding its dispersal.

The leopard toadfish.

Photo: Flickr

The Leopard Toadfish (Opsanus pardus) is a larger toadfish reaching 12 inches. They too have a light-colored body with dark markings. It prefers reefs and rocky areas offshore. The only ones I have seen, or captured, were on our artificial reefs. It was noted early on in the lionfish invasion, that lionfish were not as numerous on reefs where leopard toadfish existed. This spawned a hypothesis that leopard toadfish may actually consume lionfish. A small study conducted at a local high school marine science program found that was not the case. I am not aware of any further studies on the relationship between these two, but it could be they just compete for space and the leopard toadfish wins some of these. Though not reported from Argentina, this species does have a large range – including the entire U.S. Atlantic seaboard, the entire Gulf of Mexico, and much of the Caribbean. Again, few barriers to their dispersal.

The common estuarine Gulf toadfish.

Photo: Flickr

The most frequently encountered toadfish is the Gulf Toadfish (Opsanus beta) – also know as the oyster dog, dogfish, or mudfish. This is the largest of the native toadfish at 15 inches. It is most common inside our estuaries living on oyster reefs, burrows in seagrass beds, jetties, and any sunken debris such as pipes, concrete, or pilings. Because of its habitat choice, this toadfish is much darker in color, having some light bars or markings on its side. This is the species that is sometimes found in sunken bottles and cans. This is a Gulf species found throughout the Gulf of Mexico, and some portions of the West Indies, but absent from most of the Caribbean and the Atlantic coast where it is replaced by its close cousin Opsanus tau. There does seem to be a barrier near the Florida straits that impedes its dispersal east and north of the Gulf. There are two species on each side suggesting a long period of isolation from each other and no interbreeding. Again, there is a barrier there.

I am not sure whether you have seen any of the local toadfish while snorkeling or diving. They are occasionally caught on rod and reel, but not often. However, now that you know about them, I am sure you will see one while out on the waters.

Reference

Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 21, 2021

Catfish…

There are a lot of fish found along the Florida panhandle that many are not aware of, but catfish are not one of them. Whether a saltwater angler who captures one of those slimy hardhead catfish to a lover of freshwater fried catfish – this is a creature most have encountered and are well aware of.

Growing up fishing along the Gulf of Mexico, the “catfish” was one of our nemesis. Slinging your cut-bait out on a line, if you were fishing near the bottom, you were likely to catch one of these. Reeling in a slimy barb-invested creature, they would swallow your bait well beyond the lip of their mouths and it would begin a long ordeal on how to de-hooked this bottom feeder that was too greasy to eat. Many surf fishermen would toss their bodies up on the beach with the idea that removing it would somehow reduce their population. Obviously, that plan did not work but ghost crabs will drag their carcasses over to their burrows where they would consume them and leave the head skull that gives this species of catfish it’s common name “hardhead” catfish, or “steelhead” catfish. This hard skull has bones whose shape remind you of Jesus being crucified and was sold in novelty stores as the “crucifix fish”.

The bones in the skull of the hardhead catfish resemble the crucifixion of Christ and are sold as “crucifix fish”.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

When I attended college in southeast Alabama a group of friends wanted to go out for fried catfish. I, knowing the above about saltwater catfish, replied “why?… no…, you don’t eat catfish”. They assured me you did and so off we went to a local restaurant who sold them. Fried catfish quickly became one of my favorites. A fried catfish sandwich with slaw and beans is something I always look forward to. At that time, I was not aware of the freshwater catfish, nor the catfish farms that produce much of the fish for my sandwiches. I now have also become aware of the method of catching freshwater catfish called “noodling” – which is not something I plan to take up.

Worldwide, there are 36 families and about 3000 species of what are called catfish1. Most are bottom feeders with flatten heads to burrow through the substrate gulping their prey instead of biting it. Most possess “whiskers” – called barbels, which are appendages that can detect chemicals in the environment (smell or taste) helping them to detect prey that is buried or hard to find in murky waters. These barbels resemble whiskers and give them their common name “catfish”.

The serrated spines and large barbels of the sea catfish. Image: Louisiana Sea Grant

They lack scales, giving them the slimy feel when removing them from your hook, and also have a reduced swim bladder causing them to sink in the water – thus they spend much of their time on the bottom. The mucous of their skin helps in absorbing dissolved oxygen through the skin allowing them to live in water where dissolved oxygen may be too low for other types of fish1.

They are also famous for their serrated spines. Usually found on the dorsal and pectoral fins, these spines can be quite painful if stepped on, or handled incorrectly. Some species can produce a venom introduced when these spines penetrate a potential predator which have put some folks in the hospital1.

The size range of catfish is large; from about five inches to almost six feet. In North America, the largest captured was a blue catfish (Ictalurus furcatus) at 130 pounds. The largest flathead catfish (Pylodictis olivaris) was 123 pounds. But the monster of this group is the Mekong catfish of southeast Asia weighing in at over 600 pounds.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission lists six species of catfish in the Florida panhandle area. However, they are focusing on species that people like to catch2.

The Blue Catfish

Photo: University of Florida

This large blue catfish is being weighed by FWC researchers. Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

The Channel Catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) is found throughout Florida and also in many river systems of the eastern United States. It has found few barriers dispersing through these river systems. They are not typically bottom feeders having a more carnivorous diet.

The Flathead Catfish (Pylodictis olivaris) are relatively new to Florida and are currently reported in the Escambia and Apalachicola rivers. They prefer these slow-moving alluvial rivers.

The Blue Catfish (Ictalurus furcatus) were first reported in the Escambia and Yellow Rivers, there are now records of them in the Apalachicola. These catfish prefer faster moving rivers with sand/gravel bottoms and seem to concentrate towards the lower ends of major tributaries.

The White Catfish (Amerius catus) is found in rivers and streams statewide, and even in some brackish systems.

The Yellow Bullhead (Amerius natalis) are most often found in slow moving heavily vegetated systems like ponds, lakes, and reservoirs. It is reported to be more tolerant of poor water conditions.

The Brown Bullhead (Amerius nebulosus) live in similar conditions to the Yellow Bullhead.

The dispersal of freshwater catfish is interesting. How do they get from the Escambia to the Apalachicola Rivers without swimming into the Gulf and up new rivers? The answer most probably comes from small tributaries further upstream that can, eventually, connect them to a new river system. Scientists know that eggs deposited on the bottom can be moved by birds who feed in each of the systems carrying the eggs with them as they do. And you cannot rule out movement by humans, whether intentionally or accidentally.

On the saltwater side of things, there are two species – though the blue catfish has been reported in the upper portions of some estuaries in low salinities in the western Gulf of Mexico. The marine species are the hardhead catfish (Arius felis), sometimes known as the “steelhead” or the “sea catfish” – and the gafftop (Bagre marinus), also known as the gafftopsail catfish3.

The hardhead catfish is very familiar with anglers along the Gulf coast. This is the one I was referring to at the beginning of this article. It is considered inedible and a nuisance by most. They are common in estuaries and the shallow portions of the open sea from Massachusetts to Mexico. They are reported to have an average length of two feet, though most I have captured are smaller. Like many catfish, they possess serrated spines on their dorsal and pectoral fins. Their distribution seems to be limited by salinity.

The gafftop is also reported to have a mean length of two feet, and most that I have captured are closer to that. At one point in time, we were longlining for juvenile sharks in Pensacola Bay and caught numerous of these thinking they were small bull sharks as we pulled the lines in, until we saw the long barbels extending from them. I remember this being a very slimy fish, covered with mucous, and not fun to take off the hooks. It is reported to have good food value, though I have not eaten one. They differ from the hardheads mainly in their extended rays from the dorsal and pectoral fins. The habitat and range are similar to hardheads, though they have been reported as far south as Panama.

The extended rays of the gafftop catfish.

Photo: University of Florida.

The diversity of freshwater catfish in the U.S. goes beyond what has been reported here. This group has been found on most continents and have been very successful. There are plenty of local catfish farms where you can try your luck, have them cleaned, and enjoy a good meal.

References

1 Catfish. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catfish.

2 Catfish. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. https://myfwc.com/fishing/freshwater/sites-forecasts/catfish/.

3 Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 2, 2021

Eels… when that name comes up most think of either the vicious moray eels or the famous electric eel. Moray eels do exist in the Florida panhandle, and we will talk about them. Electric eels do not, they are found in the Amazon River system. That said, we do have eels here – quite a few. There are at least 18 species found in six different families. Most are 2-3 feet in length, though the Banded Shrimp Eel (Ophichthus) can reach six feet. About half of them are found offshore on the middle and outer shelves, the other half can be found in the inner shelf and estuaries, a few species swim into freshwater. Shrimpers often catch them when trawling and occasionally anglers will catch them with rod and reel.

Eels superficially resemble snakes and sometimes are confused with them. I have been told more than once that we do have sea snakes here. We do not. What people are finding are one of the 18 species of eels in the area. We do have snakes swimming across our estuaries, but we do not have sea snakes.

Eels differ from snakes primarily in that they, being fish, possess gills – not lungs. Most eels do have sharp teeth, the morays are famous for theirs, but no eels are venomous – so no worries there. Most of our eels have very small scales or are completely scaleless and are often very slimy and difficult to handle. They have been used as bait and one species, the American eel (Anguilla rostrata), has been used for food.

The Anguilla eel, also known as the “American” and “European” eel.

Photo: Wikipedia.

The American eel has an interesting life history. They spawn in the Sargasso Sea, an area in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. Their developing leptocephalus larva are thin, flat, and transparent in the water. They drift with the ocean currents into the Gulf of Mexico and eventually into our estuaries. I have found them along the shores of Project Greenshores (in Pensacola Bay) during certain parts of the year. From here they work their ways into our local rivers where people encounter the large adults. I have found them living in submerged caves near Marianna and many locals have found them at the bottom of our rivers. When time to breed, the adults will leave and head back to the open Atlantic to begin the cycle again. An amazing trip.

Moray eel.

Photo: NOAA

Moray eels are famous for the nasty attitudes and vicious bites. They are more tropical and associated with offshore reefs, though the ocellated moray (Gymnothorax ocellatus) is often caught in shrimp trawls. They live in the crevices of the reef ambushing prey. Some, like the green moray, can get quite large – over six feet. Like all eels, they have very powerful muscles and sharp teeth.

The shrimp eel is common on our inner and middle continental shelf.

Photo: NOAA

Conger eels are very common despite few people ever seeing them. There are six species and they frequent the middle continental shelf, so are rare in estuaries.

There are eight species of snake, or worm, eels. These are more common on the inner shelf and the coastal estuaries. Many prefer muddy bottoms where they bury tail first to ambush prey swimming by.

The majority of these marine eels have a large geographic distribution. Their larva can be carried great distances in the currents and their need for sandy or muddy bottoms can be met just about anywhere. They appear to have few barriers keeping them from colonizing much of the Gulf and surrounding waters. Most fall into the category we call “Carolina Fish”. Meaning their distribution occurs from the Carolinas, throughout the Gulf of Mexico, south to Brazil. There are a few species that can tolerate the lower salinities of the estuaries and one, the Anguilla eel, that can even venture into freshwater.

There are few species restricted to the tropical reefs, such as the morays. But morays are found on our smaller middle shelf and artificial reefs in the northern Gulf. Though found in parts of the Atlantic Ocean, Hoese and Moore1 reported one species of conger eel, Uroconger syringus, as only occurring near south Texas in the Gulf of Mexico. What barriers keep it from colonizing other Gulf habitats is unknown.

Eels are true fish that we rarely encounter. Encounters are usually startling but exciting at the same time. They are pretty amazing fish.

Reference

Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M University Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 18, 2021

This is a famous fish. If you look back at the old tourism magazines of the early 20th century you will see a lot about tarpon fishing in Florida. As a matter of fact, some say that tarpon fishing was the beginning of the tourism industry in the state. Also known as “silver kings”, they put up a tremendous fight which anglers love, particularly on lighter tackle. It is a sport fish, not sought for food, so catch and release has been the rule for years. But those who seek them will tell you it is worth the fight even if you must release it.

Tarpon have been a popular fishing target for decades.

Photo: NOAA

Tarpon (Megalops atlantica) are large bodied, large scaled fish, with a deep blue back and silver sides. They are a large fish, reaching over 8 feet in length and up to 350 pounds. They tend to travel in schools and are often associated with other fish, such as snook2.

It has always been thought of as a “south Florida fish”. As mentioned, down there it is a popular fishing target for tourist and residents alike. Many charter captains specialize in catching the fish and they have been featured in fishing programs. But you do not hear about such things in the Florida panhandle. Hoese and Moore1, as well as the Florida Museum of Natural History2 both indicate that they are in fact in the Florida panhandle. As a matter of fact, this fish has few barriers and has the distribution of the classic “Carolina fish” group. That includes the entire eastern seaboard of the United States, the entire Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean1. The Florida Museum of Natural History indicates they are found on the opposite shores of the Atlantic Ocean and may have made their way through the Panama Canal to the Pacific shores of the canal. Within this range they are known to enter freshwater rivers. They seem to have few biogeographic barriers.

I grew up in the panhandle and remember hearing about them swimming in our area when I was younger. Fishermen said they would throw all sorts of bait at them. Artificial lures, live bait, cut bait, you name it – they tossed it… the tarpon never would take it. Catching one here was almost impossible. The flats fishing charter trips for tarpon in south Florida would not happen here. I remember once diving in Pensacola Bay near Ft. Pickens. We were looking for an old Volkswagen beetle that had been sunk years ago when at one point the water became very dark – almost like storm clouds had rolled in. When my buddy and I both looked up we saw a school of very large fish swimming above us. We were not sure what they were at first but as we slowly ascended, we realized they were tarpon. It was pretty amazing.

An interesting side note here. In 2020 tarpon were once again seen swimming around the Pensacola area but this time they WERE taking bait. There were several reports of tarpon caught off the Pensacola Fishing Pier and inside the bay. Why change over all this time? I am not sure.

The ladyfish (or skipjack) is the smaller cousin of the tarpon, but puts up a good fight as well.

Photo: University of Southern Mississippi

Tarpon belong to the family Elopidae which also includes another local fish known as the “ladyfish” or “skipjack” (Elops saurus). This is a much smaller fish reaching about 3 feet (and that would be a large ladyfish). The scales of this family member are much smaller, but the fight on hook and line is just as large. The characteristic that places these two fish into the same family (and these are the only two in this family) is the hard bony gular plate found between the right and left side of the lower jaw (in the “throat” area).

Like tarpon, it is not prized as a food fish but more of a game fish. It has the classic wide distribution of the “Carolina fish group” – the eastern seaboard of the United States, the Gulf of Mexico, down to Brazil. Like the tarpon, it is found in brackish conditions but is not mentioned in freshwater. Again, few biogeographic barriers for this fish.

Both members of this family provide anglers young and old with a lot of enjoyment.

1 Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

2 Discover Fishes. Tarpon. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/megalops-atlanticus/.

3 Discover Fishes. Ladyfish. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/elops-saurus/.