by Rick O'Connor | Aug 8, 2021

Like the ancient sturgeon, this is one strange prehistoric looking group of fish. I’ll say group of fish because there is more than one kind. For many, all gars are alligator gars. There is an alligator gar but there are others. Actually, the longnose gar may be seen more often than the alligator gar, but many do not know there is more than one kind.

Gars are freshwater fish, but several species have a high tolerance for saltwater. The alligator gar (Artactosteus spatula) has been reported from the Gulf of Mexico1. They are elongated, slow moving fish with extended snouts full of sharp teeth – very intimidating to look at. But swimming with gars in springs and rivers, I have found them to be oblivious to me. Snag one in a net however, and they will turn quickly and could do serious harm. While fishing my grandson had one come after his bait once and that was pretty exciting, but it is rare to catch them on hook and line. Many who fish for them do so with bow and arrow. Their skin is covered with tough ganoid scales. You really can’t scale them; you have to skin them.

Alligator Gar from the Escambia River.

Photo: North Escambia.com

In the book Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico, by Hoese and Moore, they list four species of gar in the northern Gulf. As the name suggests, the longnose gar (Lepisosteus osseus) has a long slender snout and has spots on the body. It is the one most often seen by people visiting our springs, rivers, and the one most often seen in our estuaries. It can reach a length of five feet3.

The famous alligator gar (Artactosteus spatula) has a shorter snout and spots are usually lacking. If they do have them, the are usually on the fins. This is a big boy – reaching lengths of nine feet and up to 100 pounds2. They are common in coastal estuaries and even the Gulf, though not encountered very often.

The spotted gar (L. oculatus) also has a short snout but has spots all over its body. It prefers the rivers and will enter estuaries only where the salinities are low. It is smaller at four feet4.

Spotted Gar.

Photo: University of Florida

The last panhandle gar is the shortnose gar (L. platostomus). This species too prefers rivers and may enter low salinity bays. It has a short snout and lacks spots.

There is a Florida gar (L. platyrhincus) not found in the panhandle but exists along the central and south Florida gulf coast. It seems to have replaced the spotted gar in this location5.

The biogeography of this group of fish is interesting in that it is an ancient like the sturgeon, it existed during a time period when much of Florida would have been underwater. The general range of gars is the entire eastern United States. They prefer slow moving rivers, or backwaters of faster rivers, and are common in springs. As mentioned, a few species will venture into saltwater and can be found around the Gulf of Mexico. But with several species there has obviously been some speciation over time.

The common longnose gar.

Photo: University of South Florida.

The longnose gars have one of the widest distributions within the group. They are found in most river systems across the eastern United States and all of Florida. It seems to have few barriers including saltwater.

Alligator gars have a similar distribution but seem to be restricted from the peninsula part of Florida. The Florida rivers where they are found are all in the panhandle and are all alluvial rivers – muddy and not tannic like the Suwannee. This could be due to required food that prefer alluvial rivers, pH (pH is lower in the tannic rivers), or something else. Though they did not disperse into central and south Florida, they did extend their range westward down into Mexico. And, as mentioned, have been reported in the open Gulf of Mexico.

Spotted gars follow a similar distribution to the alligator gar. Much of the Mississippi River basin, Florida panhandle, and west to Texas – but they are not found in peninsular Florida. Pre-dating the emergence of peninsular Florida from the sea, there was some barrier that prevented them from dispersing south when the landmass did appear.

A different species appeared in peninsular Florida along with the longnose gar – the Florida gar. It is found in central and south Florida and has dispersed a little north along the Atlantic coast to Georgia.

This is an interesting group of ancient fish. Some are commercially harvested and have suffered from human alterations of river systems. They are amazing to see.

1 Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

2 Discover Fishes. Florida Museum of Natural History. Alligator Gar. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/florida-fishes-gallery/alligator-gar/.

3 Discover Fishes. Florida Museum of Natural History. Longnose Gar. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/florida-fishes-gallery/longnose-gar/.

4 Discover Fishes. Florida Museum of Natural History. Spotted Gar. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/florida-fishes-gallery/spotted-gar/.

5 Discover Fishes. Florida Museum of Natural History. Florida Gar. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/florida-fishes-gallery/florida-gar/.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 29, 2021

Sargassum washed ashore after a storm on Pensacola Beach. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

I am sure it drives the tourists a little crazy. After daydreaming all year of a week relaxing at the beach, they arrive and find the shores covered in leggy brown seaweed for long stretches. It floats in the shallow water, tickling legs and causing a mild panic—was that a fish? A jellyfish? A shark? Then, of course, high tide washes the seaweed up and strands it at the wrack line, shattering the vision of dreamy white sand beaches.

But for those visitors—and locals—willing to take a closer look, the brown algae known as sargassum is one of the most fascinating organisms in the sea. The next time you are at the beach, pick some up and turn it over in your hands. Sargassum is characterized by its bushy, highly branched stems with numerous leafy blades and berry-like, gas-filled structures. The tiny air sacs serve as flotation devices to keep the algae from sinking. This unique adaptation allows it to fulfill a niche at the top of the water column, instead of growing at the bottom or on another organism.

The sargassum fish blends incredibly well into its home within sargassum mats. It uses handlike pectoral fins to move around. Photo credit: Reef Builders

Sargassum tends to accumulate into large mats that drift through the water in response to wind and currents. These drifting mats create a pelagic habitat that attracts up to 70 species of marine animals. Several of these organisms are adapted specifically to life within the sargassum, reaching full growth at miniature sizes and camouflaged in shape, pattern, and color to blend in. These very specialized fauna include the sargassum crab, the sargassum shrimp, sargassum flatworm, sargassum nudibranch, sargassum anemone, and the sargassum fish! The sargassum fish (Histrio histrio) is in the toadfish family, a group of slow-moving reef fish that pick their way through coral and algae by using their pectoral fins like hands. Sea turtle hatchlings will spend their early years feeding and resting within the relative safety of large mid-ocean sargassum mats.

The small air-filled sacs of sargassum allow it to float on the surface, becoming the basis of a teeming ecosystem. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Over time the air sacs lose buoyancy and the sargassum sinks, providing an important source of food for bottom-dwelling creatures. If washed ashore, many of the animals abandon the sargassum or risk drying out and dying.

In general, most of the larger, familiar seaweeds like sargassum are brown algae. Brown algae (including kelp and rockweed) have colors ranging from brown to brownish yellow-green. These darker colors result from the brown pigment fucoxanthin, which masks the green color of chlorophyll. Extractions from brown algae are commonly used in lotions and even heartburn medication!

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 9, 2021

This is one strange, primitive, dinosaur-looking fish. They have large scutes embedded in their skin that give them an armored look. They are big – reaching 14 feet in length and 800 pounds (though the Gulf sturgeon does not reach the large size of their cousin the Atlantic sturgeon). They resemble sharks with their heterocercal caudal fin and possess long whiskers (barbels) suggesting a benthic mode of feeding.

Sturgeon are large fish. The barbels (whiskers) are for finding prey buried in the sediment. Notice the raised ganoid scales of this ancient creature.

Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Panhandle residents know them from their impressive leaps as they head upriver for spawning in the spring. The loud splash from one of these leaps can be heard for a long distance and is a concern for boaters who may be zipping up and down one of the local rivers on a jet sky, or even a bass boat. When in college, we asked one of the professors – “why do mullet jump?”. He paused for a second and responded – “for the same reason manta rays jump”. There was another longer pause. Understanding what was going on we took the bait and asked – “okay… why do manta rays jump?” – “we don’t know”. However, that was in 1980 and a lot has been learned since. We know that not only do mullet and mantas leap, but baleen whales and sturgeon do as well. It is believed that baleen whales leap to communicate during the breeding season. Since sturgeon breed in panhandle rivers, it is believed that this is the reason they may do so. Scientists have also found it helps adjust their swim bladders with internal gas making them more buoyant in the water.

Like salmon, sturgeon swim up rivers to breed and spawn in the spring. Fertilization is external and the gray-black eggs are laid on the substrate at the bottom. The newborn and adults spend the remaining spring in the rivers, and the adults do not feed at this time. In summer all head for the estuaries where the adults begin feeding with a vengeance. They feed on a variety of benthic invertebrates and prefer sections of the bay that are well oxygenated. Sturgeon spend the summer and much of the fall in the bays until the temperatures begins to drop at which time they head into the open Gulf of Mexico. The spring, they find their breeding rivers and the reproductive cycle begins again. This is a long-lived fish, reaching up to 50 years in age.

As far as the biogeography of this species, it is an interesting one. They have been around for about 200 million years. This was about the time the whole “Pangea” movement was going on – Florida did not look like Florida then. There was an opening between what is now the southeastern United States and the Florida peninsula. The water moving through this was called the Georgia Seaway or the Suwannee Channel. This allowed marine species to easily move from the Atlantic to the Gulf of Mexico. It was believed the current in this seaway was significant enough to keep silt and clays from reaching what would be become peninsula Florida, which was probably a submerged region of islands at the time.

During those times the Atlantic sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus) inhabited this region, using southeast rivers for breeding. About 25 million years ago global land mass changes began a period of ice formation that encouraged sea level to drop and the peninsula portion of Florida was exposed – the Florida people know today. However, this new peninsula isolated populations of sturgeon (and other fish at that time) from reaching each other. As time moved on, different genetic changes occurred in both populations to produce offspring that varied from each other. These external morphological changes were enough to let you know they were different, but genetically they are close enough to still breed. In these situations, they have deemed “subspecies” of each other. The Atlantic sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus) and the Gulf sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus desotoi). It is the Gulf sturgeon we find along the panhandle. This process of producing new subspecies and species due to population isolation over time is called speciation.

Another interesting trend is the original range of the Gulf sturgeon was from the Texas/Louisiana border to about Tampa Bay. This suggest that the fish took advantage of numerous rivers for breeding but there was a barrier as you reach the tropics. Whether that barrier was climatic (temperature) biological (food source) or something else I am not sure. With the high concentration of sturgeon in the panhandle you might think they require the alluvial rivers of this region. But sturgeon are as common in tannic rivers, such as the Suwannee and Yellow Rivers, as they are in those alluvial ones, such as the Escambia and Apalachicola.

Today, their range is even smaller. They are now found only in the rivers between Louisiana/Mississippi border to the Suwannee River. This range reduction is probably due to habitat alteration (much of it human induced – such as dams) and overharvesting (the eggs of the sturgeon are used for caviar). Today all species and subspecies of sturgeon are protected by the endangered species act.

Because this is an ancient fish, the biogeographic story of the sturgeon is an interesting one and shows how speciation occurs over time with all life. They are really cool fish and, if you have not seen one leap yet, I hope you get to. It is pretty amazing.

References

Florida’s Geologic History, University of Florida IFAS, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/UW208.

NOAA Species Directory, Gulf Sturgeon, https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/gulf-sturgeon.

NOAA Species Directory, Atlantic Sturgeon, https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/atlantic-sturgeon.

Sturgeon, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, https://myfwc.com/conservation/you-conserve/wildlife/sturgeon/#:~:text=When%20the%20ambient%20pressure%20changes,to%20communicate%20with%20other%20sturgeon..

by Erik Lovestrand | Mar 11, 2021

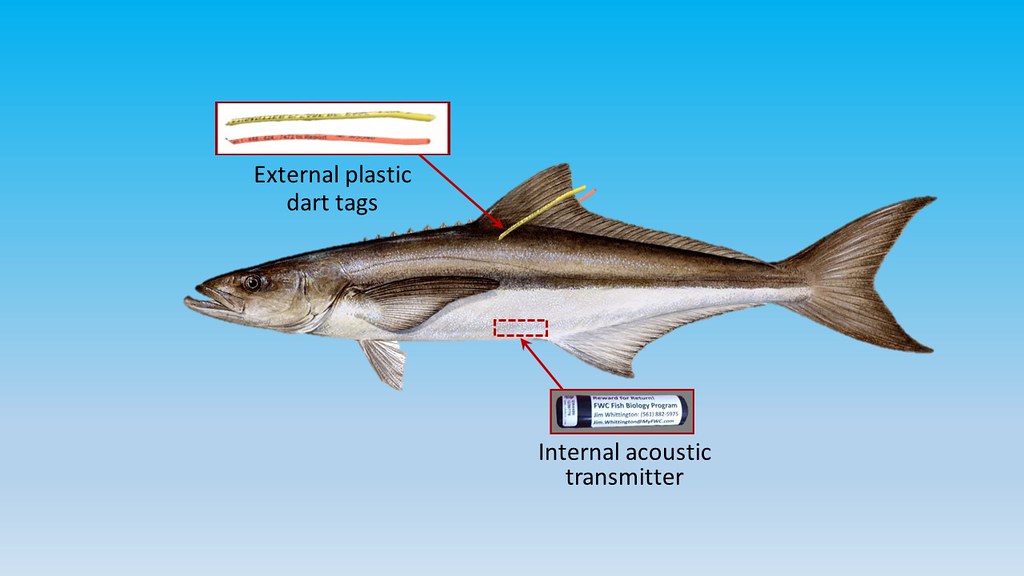

Cobia Researchers use Transmitters as well as Tags to Gather Data on Migratory Patterns

I must admit to having very limited personal experience with Cobia, having caught one sub-legal fish to-date. However, that does not diminish my fascination with the fish, particularly since I ran across a 2019 report from the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission titled “Management Profile for Gulf of Mexico Cobia.” This 182-page report is definitely not a quick read and I have thus far only scratched the surface by digging into a few chapters that caught my interest. Nevertheless, it is so full of detailed life history, biology and everything else “Cobia” that it is definitely worth a look. This posting will highlight some of the fascinating aspects of Cobia and why the species is so highly prized by so many people.

Cobia (Rachycentron canadum) are the sole species in the fish family Rachycentridae. They occur worldwide in most tropical and subtropical oceans but in Florida waters, we actually have two different groups. The Atlantic stock ranges along the Eastern U.S. from Florida to New York and the Gulf stock ranges From Florida to Texas. The Florida Keys appear to be a mixing zone of sorts where Cobia from both stocks go in the winter. As waters warm in the spring, these fish head northward up the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of Florida. The Northern Gulf coast is especially important as a spawning ground for the Gulf stock. There may even be some sub-populations within the Gulf stock, as tagged fish from the Texas coast were rarely caught going eastward. There also appears to be a group that overwinters in the offshore waters of the Northern Gulf, not making the annual trip to the Keys. My brief summary here regarding seasonal movement is most assuredly an over-simplification and scientists agree more recapture data is needed to understand various Cobia stock movements and boundaries.

Worldwide, the practice of Cobia aquaculture has exploded since the early 2000’s, with China taking the lead on production. Most operations complete their grow-out to market size in ponds or pens in nearshore waters. Due to their incredible growth rate, Cobia are an exceptional candidate for aquaculture. In the wild, fish can reach weights of 17 pounds and lengths of 23 inches in their first year. Aquaculture-raised fish tend to be shorter but heavier, comparatively. The U.S. is currently exploring rules for offshore aquaculture practices and cobia is a prime candidate for establishing this industry domestically.

Spawning takes place in the Northern Gulf from April through September. Male Cobia will reach sexual maturity at an amazing 1-2 years and females within 2-3 years. At maturity, they are able to spawn every 4-6 days throughout the spawning season. This prolific nature supports an average annual commercial harvest in the Gulf and East Florida of around 160,000 pounds. This is dwarfed by the recreational fishery, with 500,000 to 1,000,000 pounds harvested annually from the same region.

One of the Cobia’s unique features is that they are strongly attracted to structure, even if it is mobile. They are known to shadow large rays, sharks, whales, tarpon, and even sea turtles. This habit also makes them vulnerable to being caught around human-made FADs (Fish Aggregating Devices). Most large Cobia tournaments have banned the use of FADs during their events to recapture a more sporting aspect of Cobia fishing.

To wrap this up I’ll briefly recount an exciting, non-fish-catching, Cobia experience. My son and I were in about 35 feet of water off the Wakulla County coastline fishing near an old wreck. Nothing much was happening when I noticed a short fin breaking the water briefly, about 20 yards behind a bobber we had cast out with a dead pinfish under it. I had not seen this before and was unaware of what was about to happen. When the fish ate that bait and came tight on the line the rod luckily hung up on something in the bottom of the boat. As the reel’s drag system screamed, a Cobia that I gauged to be 4-5 feet long jumped clear out of the water about 40 yards from us. Needless to say, by the time we gained control of the rod it was too late; a heartbreaking missed opportunity. Every time we have been fishing since then, I just can’t stop looking for that short, pointed fin slicing towards one of our baits.

by Chris Verlinde | Mar 5, 2021

On most days, if you walk to the end of the Navarre Beach Fishing Pier, you will find a group of shark anglers that provide valuable data to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Cooperative Volunteer Shark Tagging program. Led by Earnie Polk, 50-60 team members have participated in the cooperative tagging program in the twenty-five years he has been involved.

program in the twenty-five years he has been involved.

This group not only provides research data to NOAA, but are also stewards of pier etiquette, Navarre Beach and the surrounding area. Tourists and locals alike are treated to stories of local history, fish tales and general information about the area from Earnie and Team True Blue members. In addition, visitors may see a shark tagged and released or the group catching large fish to be used for shark bait

Photo Credit Earnie Polk

The NOAA Cooperative Shark Tagging program has been in existence since 1962. Today thousands of anglers along the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coast have tagged more than 295,000 sharks representing 52 different species. More than 17,500 sharks have been recaptured! This program provides information on shark migration patterns, numbers, locations, migrations, age and growth rates, behavior and mortality.

Earnie estimates he has tagged more than one-thousand sharks for the program. He has refined handling methods to have the least impact on the animal to ensure the survival of the shark after release. The team brings the shark to shore to measure the length and tag the shark just behind the dorsal fin.

Earnie shared an interesting story about tagging at least eighty Dusky sharks during a red tide event during the late fall of 2015. He noticed as the north winds blew the red tide out, an open area was created along the coast. This allowed clear water for the sharks to travel closer to shore and within distance of the tag and release team.

Today, the tiger shark is the most common shark the team tags and releases. Recently, the team tagged and released a 12’6” tiger shark. Randy Meredith, of the Navarre Newspaper agreed to share the video he edited of the Navarre Fishing Pier and the tag and release of the tiger shark in February 2021.

The team uses heavy gear, 200-pound test line and Everol reels that have drag pressure for a shorter fight to reduce stress on the animal for a better survival rate. Gear is spread along the rails at the end of the pier. Baited lines range from approximately 75 to 400 yards off the end of the pier. You probably wonder how they get their line 400 yards off the pier. Earnie has modified a fiberglass kayak with a battery powered motor. It is lowered to the surface of the water; team members drop their lines onto the kayak and Earnie pilots the kayak out to deeper water.

The team uses heavy gear, 200-pound test line and Everol reels that have drag pressure for a shorter fight to reduce stress on the animal for a better survival rate. Gear is spread along the rails at the end of the pier. Baited lines range from approximately 75 to 400 yards off the end of the pier. You probably wonder how they get their line 400 yards off the pier. Earnie has modified a fiberglass kayak with a battery powered motor. It is lowered to the surface of the water; team members drop their lines onto the kayak and Earnie pilots the kayak out to deeper water.

Their strategy is that by dropping more lines, at different depths and locations a shark is bound to trip over one of the lines. They use bait they catch on the pier or other fishing trips. Something big had hit on a cow nose ray over the weekend, so most members were using rays for bait. One team member said, “if the fish had hit on a watermelon, we all would be using watermelon for bait.” These guys have a great sense of humor!!

Make sure that the next time you visit Navarre Beach, you take time to walk out to the end of the fishing pier to learn about local sharks,  history and the area from these interesting, funny and helpful anglers. On clear days you may see sharks, rays, sea turtles and other types of marine life as you venture out.

history and the area from these interesting, funny and helpful anglers. On clear days you may see sharks, rays, sea turtles and other types of marine life as you venture out.

Be sure to stop at the pier store to pay the $1.00 per-person fee to enjoy the view!

by Mark Mauldin | Feb 5, 2021

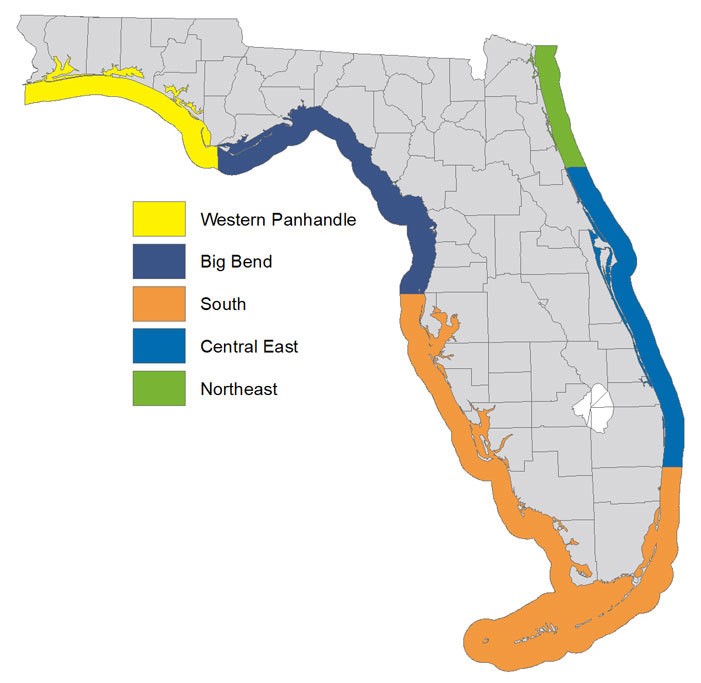

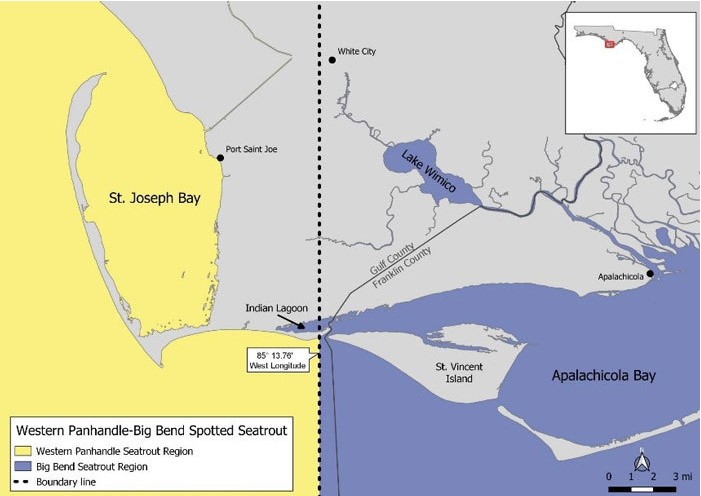

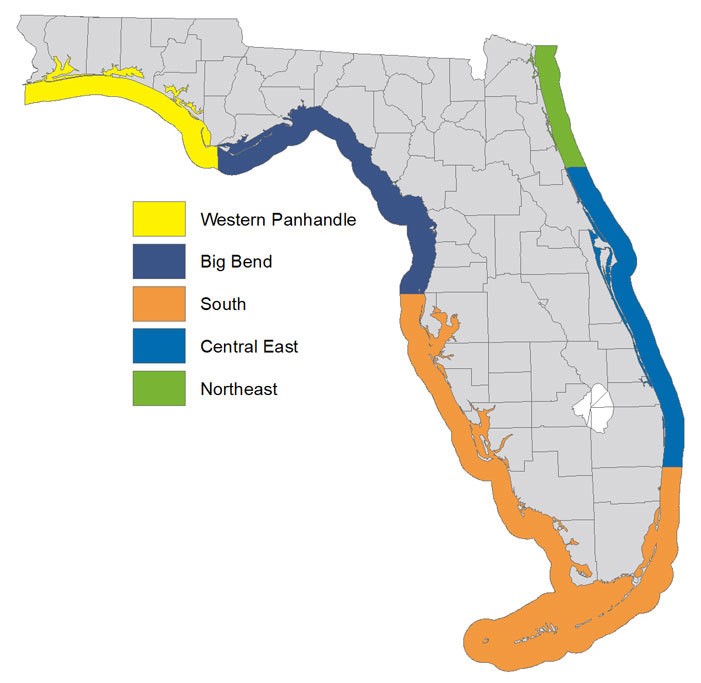

Reminder: Spotted seatrout harvest is closed in the Western Panhandle Management Zone the entire month of February.

New regulations were put into place last year reducing bag limits and closing harvest during February in the Western Panhandle Management Zone. For more details see my previous post on the subject.When Spotted Seatrout season is open (months other than February) in the Western Panhandle Management Zone the daily bag limit is 3 per harvester. Harvested Spotted Seatrout must be more than 15 inches long and less than 19 inches long. One fish, per vessel, over 19 inches my be included in the bag limit.

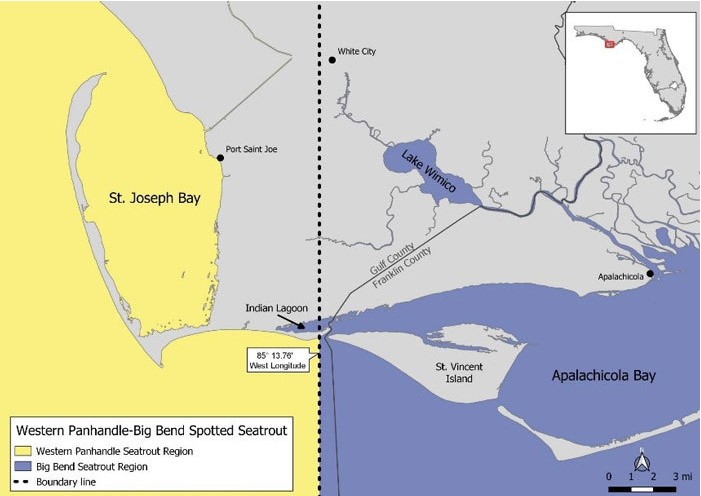

The Western Panhandle Spotted Seatrout Management Zone includes the State and federal waters of Escambia County through the portions of Gulf County west of longitude 85 degrees, 13.76 minutes but NOT including Indian Pass/Indian Lagoon.

Boundary between the Western Panhandle and Big Bend spotted seatrout management zones.

Image source: www.myfwc.com

See myfwc.com for complete information on all game and fish regulations in Florida.