by Laura Tiu | Sep 11, 2020

When one thinks of the Emerald Coast, visions of sparkling water, baby-powder beaches, rental houses and high-rises interwoven with seafood and pizza restaurants appear. The coast is dotted with fishing boats, pirate ships and dolphin cruises and the beaches are littered with people. But it is what glides under the water that some people are curious about. “Are there sharks in the water here?” is a question I often get from locals and tourists alike. The answer is yes, sharks call saltwater home.

Sharks evoke a variety of emotions in people. Some folks are fascinated and list shark fishing and diving with a shark on their bucket lists. Others are terrified, convinced that sharks only exist to hunt them and bite them while they take a swim. Unfortunately for the sharks, their appearance plays into this later fear, with sharp teeth, unblinking eyes and sleek bodies. The reality is that most sharks only grow up to three feet in length and eat small shrimp, crabs and shrimp, not humans. But it is true that bull, tiger and great white sharks are all large species that have been known to attack humans.

Of the 540 different species of sharks in the world, there are about twelve that call the Emerald Coast home including Atlantic sharpnose, bonnet head, blacktip, bull, dusky, great white, hammerhead, nurse, mako, sand, spinner, and tiger. They don’t all stick around all year, with some migrating south in the winter, while others migrate north.

Sharks use their seven senses to interpret their environment: smell, sight, sound, pressure, touch, electroreception, and taste. Most shark attacks occur when a human is mistakenly identified as prey. There are some easy measures you can take to reduce the risk.

- Swim with others, this may intimidate sharks and allows someone to go for help if a bite occurs.

- Remove jewelry as it can look like an attractive shiny fish underwater.

- Don’t swim where folks are fishing as bait in the water may attract sharks.

- Pay attention to any schools of baitfish in the area that may be attracting sharks.

- Do not swim at dusk or dawn when visibility may be poor.

- Learn how to identify various shark species

Remember, shark attacks on humans are rare. Reports of stepping on stingrays, jellyfish stings, lightning, dangerous surf conditions and car accidents greatly outnumber the number of shark attacks every year.

For more information: https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/sharks/education-resources/

A bull shark being tagged by researchers (credit: Florida Sea Grant).

“An Equal Opportunity Institution”

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 11, 2020

There is a lot of blue out there… a whole lot of blue. Miles of open water in the Gulf with nowhere to hide… except amongst yourselves. Their blue colored bodies, aerodynamically shaped like bullets with stiff angular fins, can zip along in this vast blue openness in large schools. Their myoglobin rich red muscle increases their swimming endurance – they can travel thousands of miles without tiring. Some species are what we call “ram-jetters”, fish that basically do not stop swimming – roaming the “big blue” looking for food and avoid being eaten, following the warm currents in search of their breeding grounds.

The open water is a place for specialists. Most of these fish have small, or no scales, to reduce frictional drag. They have a well-developed lateral line system so when a member of the school turns, the others sense it and turn in unison – just as the four planes in the US Navy Blue Angels delta do – perfect motion.

Many are built for speed. Sleek bodies with sharp angular fins and massive amounts of muscle / body mass, some species can reach speeds close to 70 mph – some can “fly”. There are fewer species who can live here, as opposed to the ocean floor, but those who do are amazing – and some of the most prized commercial and recreational fishing targets in the world. Let’s meet a few of them.

Flying fish do not actually “fly”, they are gliders using their long pectoral fins.

Photo: NOAA

Flying Fish

First, they do not actually fly – they glide. These tube-shaped speedy fish have elongated pectoral fins, reaching half the length of their bodies. The two lobes of their forked tail are not the same length – the lower lobe being longer. Using this like a rudder, they gain speed near the surface and, at some point, leap – extend the large pectoral fins, and glide above the water – sometimes up to 100 yards. As you might guess, this is to avoid the sleek speedy open water predators coming after them. You might also imagine that they, and their close cousins the half-beaks, are popular bait for the bill fishermen seeking those predators.

There are eight species of these amazing fish in the Gulf of Mexico ranging in size from 6-16 inches. Most are oceanic – never coming within 100 miles of the coast, but a few will, and can, be seen even near the pass into Pensacola Bay.

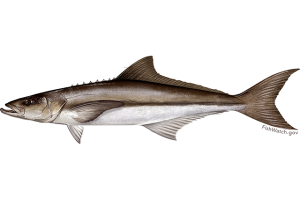

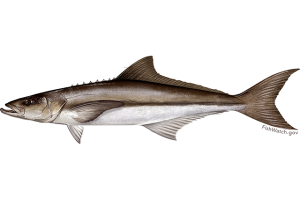

The cobia – also known as the ling, lemonfish, and sergeant fish, is a migratory species moving through our area in the spring.

Image: NOAA

Cobia

This is one of the migrating fish local anglers gear up for every year – the cobia run. When the water turns from 60° to 70°F in the spring – the cobia moves up the coastline heading from east to west. They have many different common names along the Gulf Coast. Ling, Cabio, Lemonfish, and Sergeant fish have all been used for this same animal. This is one reason biologists use scientific names – Rachycentron canadum in this case. That way we all know we are talking about the same fish. Whatever you call it, it is popular with the anglers and there is nothing like a fresh cobia sandwich – try one!

They can get quite large – 5 feet and up to 100 pounds – and resemble sharks in the water, sometimes confused with them. They seem to like drifting flotsam, where potential prey may hangout, and fishermen will toss their baits all around their schools trying to get them to take. At times, fishermen have confused sea turtles with cobia and have accidentally snagged them – only to release it, though it is a workout to do so, and they try to avoid it.

Cobia are in a family all their own. Their closest relatives are the remoras, or sharksuckers, which sometimes attach to them. They travel all over the Gulf and Atlantic Ocean.

Jacks have the sleek, fast design of the typical open water marine fish.

Photo: NOAA

Jacks

This is the largest open water family of fish I the northern Gulf – with 24 species. Not all jacks are open water, many are found on reefs and in estuaries. But these are aerodynamic shaped fish, with small scales and angular fins, and built for the open water environment. They vary in size, ranging from less than one foot, to over three. This group is identified by the two extended spines just in front of their anal fin. Several species – such as the amberjacks, pompano, and almaco jacks – are prized food fish. Others – like the jack crevalle and the blue runner (hardtail) – are just fun to catch, putting up great fights.

They are schooling fish and often associated with submerged wrecks and reefs, where prey can be found. The black and white pilot fish is called this because mariners would see them swimming in front of sharks – “piloting” them through the ocean. They are open water jacks but are more tropical and accounts in our area are rare.

The colors of the mahi-mahi are truly amazing.

Photo: National Wildlife Federation

Mahi–Mahi

This is the Hawaiian term for a fish called the dolphin (Coryphaena hippurus). You can probably guess why they prefer to call it by its Hawaiian name. It is a popular food fish, and to have “dolphin” on the menu – or to say “hey, we’re going dolphin fishing – want to come?” would raise eyebrows – and have.

The Mexicans call it “dorado”, and that term is used locally as well. Either name – it is an amazing fish. With the bull-shaped forehead of the males – they are sometimes referred to as the “bull-dolphin”. Their colors, and color changing, is amazing to see. Some biologists believe this may be some form of communication between members, don’t know, but the brilliant greens, blues, and yellows are amazing to see. They lose these colors shortly after death, so you must see it to believe it – or find one of the popular fish t-shirts.

Like jacks, dolphin like to hang around flotsam, or large schools of baitfish, looking for prey. As with many other open water predators, they will sometimes work in a team to scare, and scatter, individuals from the safety of their school. There are only two species in this family, and both are prized for their taste.

The Striped Mullet.

Image: LSU Extension

Mullet

This is not one you would typically call an “open water” fish. But in the nearshore Gulf and estuaries, they are more open water than bottom dwellers – though they do feed off the bottom. Sleek bodied, forked tail, angular fins, they have what it takes to be a fast swimmer. Though they do not “fly” as the flying fish do, they do leap out of the water. Many visitors hanging out around the Sound will hear a fish splash and immediately ask “what kind of fish was that?” Many locals will respond without looking up – “it was a mullet” – and they are probably right.

This brings up the age-old question… why do mullet jump? This was once asked of a marine biology professor. He paused… thought… and responded saying “for the same reasons manta rays jump”. That was it… another long pause. Finally, the students “took the bait” – “Okay, why do manta rays jump?”. The professor replied, “we don’t know”. So, there you go.

Another interesting thing about this fish is its wide tolerance of salinity. Mullet have been found in freshwater rivers and springs and the hypersaline lagoons of south Texas – they truly don’t care.

Locally they are popular food fish, and support a large commercial fishery in Florida, but in other parts of the Gulf not so much. It has to do with their environment and what they are feeding on. In muddier portions of the Gulf (or our bay for that matter) they have an oily taste and locals there call the “trash fish”. Even hearing that locals here eat them “grosses” them out. Local respond by giving it a more “high end” name – the Mulle (spoken with a French accent). This is actually the Cajun term for the fish. And let’s step it up a notch by adding that many locals eat mullet row – the eggs. Yea… getting hungry right? One of the popular cable food shows came here to try mullet roe. They said on a scale of 1 to 10, they give it a -4.

All that said, it is a local icon – with seafood stores selling “In Mullet We Trust” t-shirts, and the popular “Mullet Toss” event held every year on Perdido Key. It is a COOL fish.

This Spanish Mackerel has the distinct finlets of the mackerel family along the dorsal and ventral side of the body.

Image: NOAA

Mackerel

When you mention mackerel around here you usually think of one of two fish – the king mackerel (sometimes just referred to as “the king”) and the Spanish mackerel. But it is actually a large family of open water fish that includes the tuna, bonito, and the wahoo (of baseball fame).

They are some of the fastest fish in the sea, and several species are ram-jetters. Sleek bodies, sharp angular fins, they can be identified by the row of small finlets on the dorsal and ventral sides of their bodies near the rear. Full of red muscle, rich in myoglobin (which can hold more oxygen than hemoglobin alone), these are powerful swimming fish and very popular in the sushi trade. A bluefin tuna can be 14 feet long, 800 pounds, and bring a commercial fisherman tens of thousands of dollars. Because of this bluefin tuna are internationally protected and managed.

Another cool thing about these guys is that some species can control blood flow, and location, to help maintain a higher body temperature – “warm blooded” – allowing them to venture into colder waters of the world’s oceans. They are one of the big migratory fish we find. Following the large ocean currents, some species use this to play out their entire life cycle. Born in the warmer portions of the ocean gyres, they grow and feed in the cooler areas, returning in the warmer currents to breed.

There are 12 species in this family ranging in size from 1 to 15 feet. They have the characteristic “dark on top – light one bottom” coloration many animals have. This called countershading. It is believed to be used as a form of camouflage in the deep blue – with the darker blue-indigo on top (to blend in with the bottom if look from above) and the lighter silver-white on the bottom (to blend in with the sunlit surface if viewed from the below). This idea was used by the US Navy during World War II. If you visit our Naval Aviation Museum, you will see they painted the planes a darker blue on top and a lighter white on bottom. In hopes that the Japanese pilots would have a hard time spotting them over the Pacific Ocean. It is also believed to help with temperature control. The darker side will absorb heat, while the lighter side releases – avoiding over-heating. Amazing fish, aren’t they?

by Daniel J. Leonard | Sep 3, 2020

Overcup on the edge of a wet weather pond in Calhoun County. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Haunting alluvial river bottoms and creek beds across the Deep South, is a highly unusual oak species, Overcup Oak (Quercus lyrata). Unlike nearly any other oak, and most sane people, Overcups occur deep in alluvial swamps and spend most of their lives with their feet wet. Though the species hides out along water’s edge in secluded swamps, it has nevertheless been discovered by the horticultural industry and is becoming one of the favorite species of landscape designers and nurserymen around the South. The reasons for Overcup’s rise are numerous, let’s dive into them.

The same Overcup Oak thriving under inundation conditions 2 weeks after a heavy rain. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

First, much of the deep South, especially in the Coastal Plain, is dominated by poorly drained flatwoods soils cut through by river systems and dotted with cypress and blackgum ponds. These conditions call for landscape plants that can handle hot, humid air, excess rainfall, and even periodic inundation (standing water). It stands to reason our best tree options for these areas, Sycamore, Bald Cypress, Red Maple, and others, occur naturally in swamps that mimic these conditions. Overcup Oak is one of these hardy species. It goes above and beyond being able to handle a squishy lawn, and is often found inundated for weeks at a time by more than 20’ of water during the spring floods our river systems experience. The species has even developed an interested adaptation to allow populations to thrive in flooded seasons. Their acorns, preferred food of many waterfowl, are almost totally covered by a buoyant acorn cap, allowing seeds to float downstream until they hit dry land, thus ensuring the species survives and spreads. While it will not survive perpetual inundation like Cypress and Blackgum, if you have a periodically damp area in your lawn where other species struggle, Overcup will shine.

Overcup Oak leaves in August. Note the characteristic “lyre” shape. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

Overcup Oak is also an exceedingly attractive tree. In youth, the species is extremely uniform, with a straight, stout trunk and rounded “lollipop” canopy. This regular habit is maintained into adulthood, where it becomes a stately tree with a distinctly upturned branching habit, lending itself well to mowers and other traffic underneath without having to worry about hitting low-hanging branches. The large, lustrous green leaves are lyre-shaped if you use your imagination (hence the name, Quercus lyrata) and turn a not-unattractive yellowish brown in fall. Overcups especially shine in the winter when the whitish gray shaggy bark takes center stage. The bark is very reminiscent of White Oak or Shagbark Hickory and is exceedingly pretty relative to other landscape trees that can be successfully grown here.

Finally, Overcup Oak is among the easiest to grow landscape trees. We have already discussed its ability to tolerate wet soils and our blazing heat and humidity, but Overcups can also tolerate periodic drought, partial shade, and nearly any soil pH. They are long-lived trees and have no known serious pest or disease problems. They transplant easily from standard nursery containers or dug from a field (if it’s a larger specimen), making establishment in the landscape an easy task. In the establishment phase, defined as the first year or two after transplanting, young transplanted Overcups require only a weekly rain or irrigation event of around 1” (wetter areas may not require any supplemental irrigation) and bi-annual applications of a general purpose fertilizer, 10-10-10 or similar. After that, they are generally on their own without any help!

Typical shaggy bark on 7 year old Overcup Oak. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

If you’ve been looking for an attractive, low-maintenance tree for a pond bank or just generally wet area in your lawn or property, Overcup Oak might be your answer. For more information on Overcup Oak, other landscape trees and native plants, give your local UF/IFAS County Extension office a call!

by Erik Lovestrand | Jul 3, 2020

Most people have heard about bug-trapping plants that sustain themselves by digesting and absorbing nutrients from bugs that they catch. This gives them the ability to grow in soils of low fertility that most other plants cannot tolerate. Good examples of this in our Florida Panhandle area include several species of pitcher plants, Venus flytraps (non-native), bladderworts, sundews and butterworts. Some trap their unsuspecting prey by “trickery” with the temptation of sweet but sticky droplets. Others draw prey by the allure of various scents and as the bugs crawl down a narrow passage for the “treat”, one-way hairs prevent them from crawling back out; the “trick.”

One-way hairs is the strategy employed by the Dutchman’s Pipe (Aristolochia littoralis), surely one of the oddest looking flowers on the planet. Also called the “calico flower,” this non-native species of Aristolochia, superficially resembles the Dutchman’s pipe that the famed Sherlock Holmes smoked.

A side-view of the still-closed petals and bulbous reproductive chamber.

The plant is listed as a category II invasive on the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council’s 2017 List of Invasive Plant Species. Florida also has three native species of Aristolochia, some of which are important larval foods for the pipevine swallowtail. However, there are several non-natives that are actually toxic to butterfly larvae. All of the plants contain a chemical compound called Aristolochic acid, which is considered a strong carcinogen and has been linked to cancer in people who have used this plant as an herbal remedy. The plant has also been found to be a potent kidney toxin and many people have required renal transplants or dialysis as a result of using herbal remedies containing aristolochic acids.

Aristolochia is not alone in the world of bug attracting plants or fungi when it uses a fragrance resembling rotting meat as bait. The unique feature of this plant comes in the trapping strategy that is employed. When a fly is lured down the one-way, hairy tube into the bulbous chamber that serves to hold it’s captor, the flowers reproductive structures are encountered. During the fly’s exploration of the chamber, with no way out, pollen granules adhere to the fly’s body. Amazingly, within a day or so, the stiff hairs blocking the tubular entrance to the prison gradually relax or breakdown, allowing the fly to escape. Scientists who study these flowers all concur that a fly must have a very short memory because it isn’t long before the recent captor ventures into another Aristolochia trap to complete the flower’s pollination process.

Tiny hairs lining the tube leading to the chamber prevent escape, for a time.

The flower itself is an amazing structure of graceful lines, purplish-brown calico patterns and a bulbous reproductive chamber. However, the story behind the marvelous reproductive strategy of the plant is the hidden gem. Be aware though, that this is not a plant that would be recommended for our Panhandle flower gardens due to its habit of invading wildlands. Oh, now that you’ve struggled through this entire article trying to pronounce Aristolochia in your head, here is how you say it: uh-wrist-oh-low-kee-uh. Good luck with that.

by Sheila Dunning | Jul 3, 2020

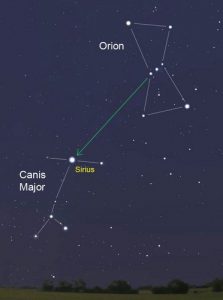

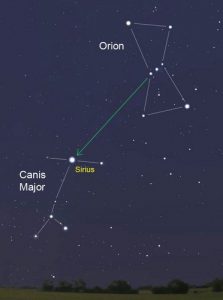

Dog Star nights Astro Bob

The “Dog Days” are the hottest, muggiest days of summer. In the northern hemisphere, they usually fall between early July and early September. The actual dates vary greatly from region to region, depending on latitude and climate. In Northwest Florida, the first weeks of August are usually the worst. So, get out before it gets hotter.

In ancient times, when the night sky was not obscured by artificial lights, the Romans used the stars to keep track of the seasons. The brightest constellation, Canis Major (Large Dog), includes the “dog star”, Sirius. In the summer, Sirius used to rise and set with the sun, leading the ancient Romans to believe that it added heat to the sun. Although the period between July 3 and August 11 is typically the warmest period of the summer, the heat is not due to the added radiation from a far-away star, regardless of its brightness. The heat of summer is a direct result of the earth’s tilt.

Life is so uncertain right now, so, most people are spending less time doing group recreation outside. But, many people are looking to get outside Spending time outdoors this time of year is uncomfortable, potentially dangerous, due to the intense heat. So, limit the time you spend in nature and always take water with you. But, if you are looking for some outdoor options that will still allow you to social distance,

try local trails and parks. Some of them even allow your dog. Here are a few websites to review the options: https://floridahikes.com/northwest-florida and https://www.waltonoutdoors.com/all-the-parks-in-walton-county-florida/northwest-florida-area-parks/ Be sure to check if they are allowing visits, especially those that are connected to enclosed spaces.

Other options may include zoos and aquariums: www.tripadvisor.com/Attractions-g1438845-Activities-c48-Florida_Panhandle_Florida.html

Or maybe just wander around some local plant nurseries:

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 2, 2020

Cooters are one of the more commonly seen turtles when visiting a freshwater system. They are relatively large for a freshwater turtle (with a carapace about 13 inches long) and are often seen basking on logs, rocks, aerator pumps, you name it – and often in high numbers while doing so. They spook easy and usually leap into the water long before you reach them. But because of their beautiful smooth shells and large size, they can be seen from a distance – looking like wet rocks on a tree limb.

A “River Cooter” seen basking on a log in Blackwater River.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

They are in the genus Pseudemys (same as the Florida red-bellied turtles) and this genus is found throughout the southeastern United States. However, from there the breakdown of species becomes a bit challenging. There has been much debate how many species there really area, and how many are subspecies of those species. There are two distinct species for sure – the “River Cooter” (Pseudemys concinna) and the “Pond Cooter” (Pseudemys floridana). From here is gets a bit weird.

The “River Cooters” are just that – friends of rivers. They like those with a bit of a current, sand/gravel bottoms, basking spots, and grasses to eat. They have been found in estuaries, even with barnacles growing on them, so they have some tolerance for saltwater. River cooters can be distinguished from their “Pond Cooter” cousins in having a more aerodynamic shell (presumably for their habit of living in faster flowing rivers) with yellow-orange markings that form concentric rings on each scute (scale) of the carapace. Some of these seem to form a backwards “C”. Their plastron is yellow-orange but will have black markings along the margins of each scute.

This river cooter is basking on a log on the heads waters of the Choctawhatchee River in Alabama.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The “Suwannee Cooter” is believed to be a subspecies (Pseudemys concinna suwanniensis) found in tannic rivers from the Ochlockonee just west of Tallahassee south to the Tampa Bay region. It has only been found in rivers that flow into the Gulf of Mexico. A couple of records have been found in rivers flowing towards the Atlantic, but it is believed these were relocated by humans.

The “Eastern River Cooter” is found from the Ochlockonee River west to Mobile Bay – possibly as far as Louisiana. There has been a suggestion that the one west of Mobile Bay is the “Mobile Cooter” (Pseudemys concinna mobilensis) but the naming of this group, again, has been a bit crazy.

As mentioned, “Pond Cooters” are fans of slow-moving waters with muddy bottoms. Unlike river cooters, pond cooters will travel over land other than to lay eggs. Many of their “pond” selections dry up and they must find new habitat. Like river cooters, pond cooters feed on vegetation so aquatic plants are must and they also like to bask in the sun on logs with many cooters basking at once.

A pond cooter in a canal within the Gulf Islands National Seashore.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Physically they differ from river cooters in having a slightly domed shell near the head end. The yellow markings are not concentric, but rather are in straight lines and their plastrons are an immaculate beautiful yellow – with no markings on the margins. They do however have black circles on the bottom margins of their carapace. These are usually round with a small yellow spot in the center – resembling an “o”.

There is believed to be two subspecies of this group. Pseudemys floridana floridiana (the “Florida Cooter”) and Pseudemys floridana peninuslaris (the “Peninsula Cooter”). Told you it was all weird. The Florida cooter is found in the Florida panhandle and the Peninsula Cooter has been found all the way to the Florida Keys – though it does not seem to be common in the Everglades.

Add to the quagmire of species identification – there is hybridization between not only the types of pond and river cooters – but BETWEEN the pond and river cooters. So, if you live in the eastern panhandle where all of these seem to converge – just call them “cooters”!

They have an interesting nesting habit. When the females approach an open sunny sandy spot, she will dig a hole to lay about 20 eggs, but she will also dig two “satellite” nests on either side – and maybe place an egg or two in there. It is quite understood why they do this, but they do. They also may come to the beach up to five times in one year to lay eggs.

A pond cooter digging a nest on someone’s property.

Photo: Deb Mozert

Because of their high numbers and large size, this has been a favorite food item for humans for quite some time. Due to this, and the practice of shooting them off their basking spots, and alterations of river systems lower the habitat quality for the river cooters, their numbers have declined. The Suwannee Cooter in particular has been hard hit and is a species of concern. Due to this it no longer allowed to harvest them (or their eggs) from the wild. Because it is so hard to tell the Suwannee from other species/subspecies of cooters – ALL cooters are now protected by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

Another note – they do not eat fish. The young will eat worms and insects, but the adults are strictly herbivores. Many pond owners want to shoot them thinking they are eating the stocked fish by the landowner. They will not eat the fish – you are fine.

I think these are amazingly beautiful animals to see glimmering in the sunny on their basking logs as you explore our local rivers and wetlands. I hope you find them just as cool and appreciate them.

Resources:

Buhlman, K., T. Tuberville, W. Gibbons. 2008. Turtles of the Southeast. University of Georgia Press, Athens GA. 252 pp.

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Freshwater Turtles https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/wildlife/freshwater-turtles/.

Meylan, P.A. (Ed.). 2006. Biology and Conservation of Florida Turtles. Chelonian Research Monographs No.3, 376 pp.