by Sheila Dunning | Mar 1, 2017

Swamp Redbay Tree infected with Laurel Wilt. Photo credit: Sheila Dunning

Many invasive plants and insects are introduced in packing materials, including 12 species of ambrosia beetles, which embed themselves in wood used as crates and pallets. While these tiny beetles don’t actually feed on wood, the adults and larvae feed on fungi that is inoculated into galleries within the sapwood by the females when they deposited their eggs. While the ambrosia fungus keeps the beetles alive, it kills the host tree. This is the projected fate of redbay trees (Persea borbonia) due to the Redbay Ambrosia Beetle.

First detected in the United States in a Georgia trap in 2002, Xyleborus glabratus, the Redbay Ambrosia Beetle, caused substantial mortality of redbay in northern Duval County, Florida in 2005. This ambrosia beetle introduces fungal spores, (Raffaelea lauricola) from specialized structures found at the base of their mandibles into the vascular system of plants when boring into host trees of the Lauraceae family. This insect and disease complex has collectively been named “Laurel Wilt.” Infected redbays, assafrass and avocado trees wilt and die within a few weeks or months.

Ambrosia Beetle life stages

The Redbay Ambrosia Beetle is a shiny black, cylindrical insect about 2 mm in length. The males are flightless and the females can only fly short distances (1 – 1.5 miles). Therefore, host trees are often attacked many times and stands of redbays are damaged quickly. Small strings of compacted sawdust may protrude from the bark at the point of initial attack. However, wind and rain easily remove this sign leaving the only symptom to be the total browning of foliage in a section of the tree’s crown. Since the fungus blocks the xylem (water-carrying) tissue of the redbay, it appears to wilt while leaves remain attached. Once infected, the trees cannot be saved.

To avoid spreading the beetle and pathogen to new areas, the trees need to be cut down and wood or chips from the infested trees should not be transported off site. Where allowed, the materials should be burned on site. Protection of unaffected trees is possible with expensive pesticides if applied in a timely manner and using the correct techniques. Removal of all susceptible tree species is not recommended. The survivors may hold a genetic tolerance.

by Carrie Stevenson | Mar 1, 2017

Special Guest Blogger – Lorraine Ketzler, Biological Science Technician with US Fish and Wildlife Service

There have been several fungal invaders entering and spreading within the US in recent years and I’d like to draw attention to four of them:

Eastern red bats being surveyed for White-nose Syndrome at Talladega National Forest, AL. Photo credit: Lorraine Ketzler

- White-nose Syndrome (WNS) in bats (Pseudogymnoascus destructans)

- Chytridiomycosis (Chytrids) in frogs (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis)

- Chytridiomycosis (B-sal) in salamanders (Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans)

- Laurel wilt disease (Raffaelea lauricola) in Lauracea family trees (redbay, sassafras, avocado and others), transferred by the invasive redbay ambrosia beetle (Xyleborus glabratus).

These diseases have devastating effects on multiple species. Bats, frogs, and salamanders are important insect predators, and all species –including trees- cycle nutrients through ecosystems to provide carbon storage benefits as well as other services. Bat populations in North America are declining precipitously as WNS marches westward across the continent. Many frog populations across the globe have disappeared because of Chytrids, with several species recorded as extinct and some are being listed under the Endangered Species Act. In addition to nutrient cycling, Lauracea trees benefit humans as food crops, aromatic ornamental trees, and medicinal plants. However, Laurel wilt disease is found in nearly every county in Florida, and continues to spread throughout the southeast.

The state and the US must remain vigilant and monitor against the introduction of B-sal, a recently discovered and highly transmissible disease spread through pet trade salamanders. It has not yet been observed in the US, but has caused widespread declines in native salamanders of the Netherlands and UK.

Unprecedented numbers of new and emerging pathogenic fungi continue to be discovered. Fungi genomes are amazingly adaptable, overcoming plant and animal defenses, and becoming resistant to fungicides. Increasing human traffic, trade, and disturbance introduce these pathogens to new habitats. Trade ports are key introduction sites. Always practice decontamination procedures when handling wildlife and native plants, even in areas without confirmed infections to prevent the spread of disease to new populations.

Help Stop the Spread of Non-native Species

by Sheila Dunning | Feb 28, 2017

Cuban Anole. Photo credit: Dr. Steve A. Johnson, University of Florida

The brown anole, a lizard native to Cuba and the Bahamas, first appeared in the Florida Keys in 1887. Since then it has moved northward becoming established in nearly every county in Florida. By hitching a ride on boats and cars, as well as, hanging out in landscape plants being shipped throughout the state, the Cuban anole (Anole sagrei) has become one of the most abundant reptiles in Florida. However, the native Carolina green anole (Anole carolinensis) has been impacted.

While both anole species are capable of thriving on the ground or in the trees, the invasive brown anole has altered the behavior of the native green anole by forcing them to remain arboreal. Anoles eat a wide variety of insects, spiders and other invertebrates. Cuban brown anoles feed on juvenile green anoles and their eggs, reducing their population even more. Brown anoles are brown to grayish in color. While they can adjust to various shades of light or dark, brown anoles cannot turn green. The native Carolina anole can camouflage itself by altering its skin color from light green to dark brown, including many hues in-between, but have no distinctive markings on their backs. Male brown anoles often have bands of yellowish spots, whereas females and juveniles have a light vertebral stripe with dark, scalloped edges. An additional identification feature is the dewlap of the male Cuban anole. Male anoles extend the skin of their lower jaw (the dewlap), displaying a bright orange to red color, in order to attract females or warn other males. Cuban brown anoles have a white line down the middle of the dewlap.

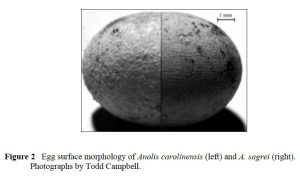

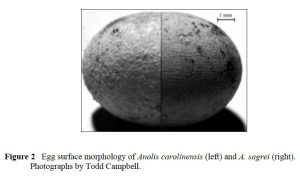

Egg surface of Native anole (left) vs Cuban anole (right). Photo credit: Todd Campbell

If the Cuban brown anole and Carolina green anole are placed side by side, the one with the shorter snout is the brown anole. Throughout the warm months, female anoles lay single, round eggs in moist soil or rotten wood at roughly 14 day intervals. The eggs of brown anoles have longitudinal grooves, whereas green anoles have raised bumps. Once identified, control measures can be taken. Brown anole eggs can be destroyed by freezing or boiling. Adult brown anoles can be located and captured by performing night time hunts with lights. Being diurnal, cold blooded creatures, Cuban anoles tend to congregate together under shrubs and along structures. Once collected the invasive Cuban brown anoles can be humanly euthanized by rubbing lidocaine on their skin and placing them in the freezer.

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 28, 2017

Torpedo grass. Photo credit: Rick O’Connor.

They say the best time to attack an invasive species is early in its arrival. In the early stages is your best chance, using the most cost effective methods, of eradicating an invasive species from a region. Hence our focus on Early Detection Rapid Response (EDRR) list. That is not the case with Torpedo Grass. It is now found in all Gulf coast states and along the Atlantic border to North Carolina. In Florida, it has been reported from 64 of the 67 counties and has also been reported in California and Hawaii. However, it is a problem plant and property owners should try to manage it as best they can.

There is a discussion as to the origins of torpedo grass (Panicum repens). Some say Europe, others Australia, but we do know it is not native to the United States. It was first introduced here in the late 19th century as a forage grass for livestock. Being a tropical-subtropical plant, the introduction was in the southeastern U.S. The young shoots have been selected by forging mammals, livestock and otherwise, but older plants become tough and the livestock ignore them for other species. There are reports of waterfowl and songbirds using torpedo grass as habitat. However, the cons out weigh the pros on this one.

Torpedo grass grows very quickly using underground rhizomes. Though they do produce seeds, these rhizomes, and their fragments, are the primary method of propagation for this plant. It has been found that rhizomes buried as deep as 20 inches can sprout shoots. This aggressive plant spreads quickly, outcompeting native grasses in disturbed areas. They will displace forage grasses that livestock prefer and can inundate a pasture very quickly. Though it is drought tolerant, torpedo grass prefers moist soils and can grow in water as deep as 6 feet. Many property owners have used this grass to control shore erosion but here is where it has causes problems for others. As on land, it grows very quickly. Spreading across shallow waterways making them unnavigable. It has caused problems with irrigation systems, stream flow, and flood control in some areas. It has also invaded citrus groves and gold courses.

So how do we deal with this plant if it is on our property?

Torpedo Grass Photo Credit: Graves Lovell, Alabama Department of Conservation & Natural Resources, www.bugwood.org

Well, we know it is not a fan of cold weather, but we are in Florida; even north Florida is suitable for it. We know it will not survive extreme hot periods. We can only hope that it will get warm enough to knock back large acres of this thing; but warm temperatures like this are not good for most plants in our area – or animals for that matter. There are no known biological controls at this time. So that means we turn to herbicides.

Experience has shown that herbicides alone will knock it back, but rarely eradicates it from the area. Chemicals that have had success are glyphosate and imazapryl. In both cases, an aquatically registered surfactant may be needed for good results. When the torpedo grass is in water, herbicide treatment can be a problem. First, the chemicals used are non-selective and may kill plants you do not want to lose. Second, mats of dead torpedo grass have been known to decrease dissolved oxygen levels (due to decomposition) to levels where fish kills can occur. Some studies have found that burning a field of torpedo grass and then treating with both glyphosate and imazapryl has had some success. Treating first and then burning has not been as successful, nor has leaving one of the three out of the program.

As common and aggressive as this grass is, you may feel any attempt to control is feudal, but doing nothing can be very costly as well. We recommend properties with patches of this grass begin treatments soon, and if you have very little – remove as soon as you can. To learn more visit one of the following websites:

Torpedo grass in Aquatic Environments

Torpedo grass Management in Turf

by Erik Lovestrand | Feb 27, 2017

Fruits on HLB infected trees ripen prematurely, are small, and often drop from tree. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand

If we look at the big picture when it comes to invasive species, some of the smallest organisms on the planet should pop right into focus. A microscopic bacterium named Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus, the cause of Citrus Greening (HLB), has devastated the citrus industry worldwide. This tiny creature lives and multiplies within the phloem tissue of susceptible plants. From the leaves to the roots, damage is caused by an interruption in the flow of food produced through photosynthesis. Infected trees show a significant reduction in root mass even before the canopy thins dramatically. The leaves eventually exhibit a blotchy, yellow mottle that usually looks different from the more symmetrical chlorotic pattern caused by soil nutrient deficiencies.

HLB, referred to as “Yellow Dragon” in China, causes an asymmetrical pattern of chlorosis in citrus leaves. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand

One of the primary vectors for the spread of HLB is an insect called the Asian citrus psyllid. These insects feed by sucking juices from the plant tissues and can then transfer bacteria from one tree to another. HLB has been spread through the use of infected bud wood during grafting operations also. One of the challenges with battling this invasive bacterium is that plants don’t generally show noticeable symptoms for perhaps 3 years or even longer. As you would guess, if the psyllids are present they will be spreading the disease during this time. Strategies to combat the impacts of this industry-crippling disease have involved spraying to reduce the psyllid population, actual tree removal and replacement with healthy trees, and cooperative efforts between growers in citrus producing areas. You can imagine that if you were trying to manage this issue and your neighbor grower was not, long-term effectiveness of your efforts would be much diminished. Production costs to fight citrus greening in Florida have increased by 107% over the past 10 years and 20% of the citrus producing land in the state has been abandoned for citrus.

Many scientists and citrus lovers had hopes at one time that our Panhandle location would be protected by our cooler climate but HLB has now been confirmed in more than one location in backyard trees in Franklin County. The presence of an established population of psyllids has yet to be determined, as there is a possibility infected trees were brought in.

Another symptom of citrus greening is small, lopsided fruit that are often bitter. Photo credit: Erik Lovestrand

A team of plant pathologists, entomologists, and horticulturists at the University of Florida’s centers in Quincy and Lake Alfred and extension agents in the panhandle are now considering this new finding of HLB to help devise the most effective management strategies to combat this tiny invader in North Florida. With no silver-bullet-cure in sight, cooperative efforts by those affected are the best management practice for all concerned. Vigilance is also important. If you want to learn more about HLB and other invasive species contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office.

by Jennifer Bearden | Feb 27, 2017

Aliens are invading our forests, pastures, fields and lawns. Well, okay, not aliens but invasive species are invading our beautiful landscapes. Invasive species are non-native or exotic species that do not naturally occur in an area, cause economic or environmental harm, or negatively impact human health. These invasive species have become the number one threat to biodiversity on protected lands. However, invasive species do not know boundaries, and as a result, public, private lands, natural and man-made water bodies, and associated watersheds are affected. National Invasive Species Awareness Week (NISAW) is February 27-March 3, 2017.

Aliens are invading our forests, pastures, fields and lawns. Well, okay, not aliens but invasive species are invading our beautiful landscapes. Invasive species are non-native or exotic species that do not naturally occur in an area, cause economic or environmental harm, or negatively impact human health. These invasive species have become the number one threat to biodiversity on protected lands. However, invasive species do not know boundaries, and as a result, public, private lands, natural and man-made water bodies, and associated watersheds are affected. National Invasive Species Awareness Week (NISAW) is February 27-March 3, 2017.

It is estimated that Florida Agriculture loses $179 million annually from invasive pests (http://www.defenders.org/sites/default/files/publications/florida.pdf). Generally, eradication of an invasive species is difficult and expensive. Most of the mitigation efforts focus on control rather than eradication.

EDDMaps (Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System), a web-based mapping system for reporting invasive species, currently has 667 different invasive plants reported in Florida. Many invasive insects, animals and diseases have also landed in Florida. Some famous invasive species in Florida include cogongrass, wild hogs, red imported fire ants, Chinese tallow, and lionfish.

For National Invasive Species Awareness Week, the University of Florida IFAS Northwest Extension District will highlight new invasive species each day. There are a couple of ways to receive this information during NISAW:

You can help us control invasive species in several ways. First, always be cautious when bringing plants or plant materials into the state. Plants or even dead plant material can harbor weeds, insects and diseases that can become invasive in our state. Second, when you see something suspicious, contact your local extension agent for help identifying the weed, insect or disease. Third, you can volunteer your time and effort. Invasive species control is difficult and requires a cooperative effort for funding and manpower. The state has several Cooperative Invasive Species Management Areas (CISMA) in which public and private organizations work together to control invasive species in their area. These CISMAs hold work days in which volunteers can help remove invasive species from the environment.

For more information about NISAW or invasive species, contact your local county extension agent.