by Matt Lollar | Dec 10, 2019

Loquat trees provide nice fall color with creamy yellow buds and white flowers on their long terminal panicles. These small (20 to 35 ft. tall) evergreen trees are native to China and first appeared in Southern landscapes in the late 19th Century. They are grown commercially in subtropical and Mediterranean areas of the world and small production acreage can be found in California. They are cold tolerant down to temperatures of 8 degrees Fahrenheit, but they will drop their flowers or fruit if temperatures dip below 27 degrees Fahrenheit.

A beautiful loquat specimen at the UF/IFAS Extension at Santa Rosa County. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS – Santa Rosa County

Leaves – The leaf configuration on loquat trees is classified as whorled. The leaf shape is lanceolate and the color is dark green with a nice soft brown surface underneath. These features help give the trees their tropical appearance.

Flowers – 30 to 100 flowers can be present on each terminal panicle. Individual flowers are roughly half an inch in diameter and have white petals.

Fruit – What surprises most people is that loquats are more closely related to apples and peaches than any tropical fruit. Fruit are classified as pomes and appear in clusters ranging from 4 to 30 depending on variety and fruit size. They are rounded to ovate in shape and are usually between 1.5 and 3 inches in length. Fruit are light yellow to orange in color and contain one to many seeds.

A cluster of loquat flowers/buds being pollinated by a honey bee. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS – Santa Rosa County

Propagation – Loquat trees are easily propagated by seed, as you will notice as soon as your tree first bears fruit. Seedlings pop up throughout yards containing even just one loquat tree. It is important to note that the trees do not come true from seed and they go through a 6- to 8-year juvenile period before flowering and fruiting. Propagation by cuttings or air layering is more difficult but rewarding, because vegitatively-propagated trees bear fruit within two years of planting. Sometimes mature trees are top-worked (grafted at the terminal ends of branches) to produce a more desirable fruit cultivar.

Loquat trees are hardy, provide an aesthetic focal point to the landscape, and produce a tasty fruit. For more information on growing loquats and a comprehensive list of cultivars, please visit the UF EDIS Publication: Loquat Growing in the Florida Home Landscape.

by Sheila Dunning | Dec 4, 2019

“Here we go ‘round the mulberry bush” is still sung by small children today. There are lots of different versions of the lyrics. But each usually describes a daily or weekly task list. In fact, the rhyme began in 1840 as a cadence for female prisoners exercising at the Wakefield Prison in England. There happened to be a Black Mulberry (Morus nigra) growing in the yard. Black Mulberry is a slow-growing short tree, so as a young tree it appears bushy.

Red Mulberry (Morus rubra) is the native Florida species. It tends to grow more upright, but is still a small tree. Additionally, there are White (Morus alba) and Pakistan (Morus macroura) , as well as, many hybrid Mulberries that will grow in the Florida panhandle. White Mulberry is a fast growing tall tree that is so aggressive that it is classified as an invasive species. It can rapidly seed natural areas and become the dominant species. But, the Pakistan Mulberry is a small tree that develops a characteristic crooked, gnarled trunk and a large fruit. It can be pruned as a bush easily.

Red Mulberry (Morus rubra) is the native Florida species. It tends to grow more upright, but is still a small tree. Additionally, there are White (Morus alba) and Pakistan (Morus macroura) , as well as, many hybrid Mulberries that will grow in the Florida panhandle. White Mulberry is a fast growing tall tree that is so aggressive that it is classified as an invasive species. It can rapidly seed natural areas and become the dominant species. But, the Pakistan Mulberry is a small tree that develops a characteristic crooked, gnarled trunk and a large fruit. It can be pruned as a bush easily.

Growing the mulberry bush can add a unique winter feature to the landscape while producing food for the birds. Yet, the plant is short enough that the fruit can be harvested without having to shake the tree and gather up the fruit from the ground before the birds get all the berries.

Mulberries are self-pollinating and only require about 400 chill hours. A chill hour is each hour that the temperature remain between 32 and 45 degrees Fahrenheit. After 400 cumulative hours the plant is able to flower. The fruit matures in the late spring to early summer. The birds will be sure to notify everyone when it’s time. Pakistan Mulberry can produce 4 inch long berries.

Mulberries will perform well if planted this winter. Plan on pruning them back each year if the bush effect is desired. It can take a year or two to get fully rooted. Don’t be surprised to see some fruit drop off prematurely as the tree/bush gets established. Also, pay attention to where the mulberry is installed. Windy spots will knock off fruit. What birds eat, they deposit. Mulberries will stain the surfaces they land on. If the fruit is walked through, the staining can be moved to indoor surfaces.

When picking fruit don’t forget the gloves unless dark stained fingers is the new look you’re trying to create.

For more information on mulberries: http://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/plants/trees-and-shrubs/trees/mulberry.html

by Matt Lollar | Oct 8, 2019

Last week at the Panhandle Fruit and Vegetable Conference, Dr. Ali Sarkhosh presented on growing pomegranate in Florida. The pomegranate (Punica granatum) is native to central Asia. The fruit made its way to North America in the 16th century. Given their origin, it makes sense that fruit quality is best in regions with cool winters and hot, dry summers (Mediterranean climate). In the United States, the majority of pomegranates are grown in California. However, the University of Florida, with the help of Dr. Sarkhosh, is conducting research trials to find out which varieties do best in our state.

In the wild, pomegranate plants are dense, bushy shrubs growing between 6-12 feet tall with thorny branches. In the garden, they can be trained as small single trunk trees from 12-20 feet tall or as slightly shorter multi-trunk (3 to 5 trunks) trees. Pomegranate plants have beautiful flowers and can be utilized as ornamentals that also bear fruit. In fact, there are a number of varieties on the market for their aesthetics alone. Pomegranate leaves are glossy, dark green, and small. Blooms range from orange to red (about 2 inches in diameter) with crinkled petals and lots of stamens. The fruit can be yellow, deep red, or any color in between depending on variety. The fruit are round with a diameter from 2 to 5 inches.

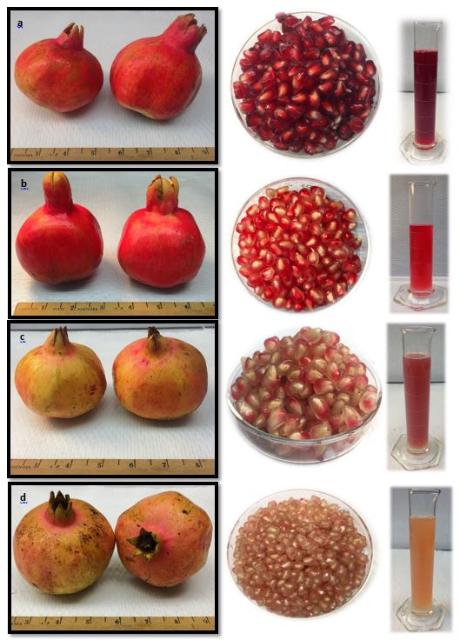

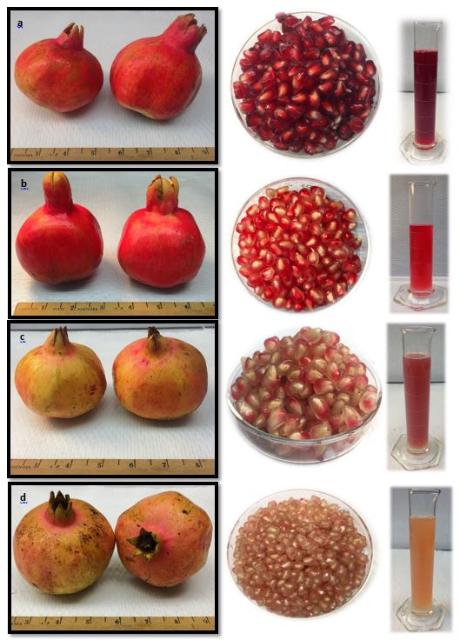

Fruit, aril, and juice characteristics of four pomegranate cultivars grown in Florida; fruit harvested in August 2018. a) ‘Vkusnyi’, b) ‘Crab’, c) ‘Mack Glass’, d) ‘Ever Sweet’. Photo Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, University of Florida/IFAS

A common commercial variety, ‘Wonderful’, is widely grown in California but does not perform well in Florida’s hot and humid climate. Cultivars that have performed well in Florida include: ‘Vkusnyi’; ‘Crab’; ‘Mack Glass’; and ‘Ever Sweet’. Pomegranates are adapted to many soil types from sands to clays, however yields are lower on sandy soils and fruit color is poor on clay soils. They produce best on well-drained soils with a pH range from 5.5 to 7.0. The plants should be irrigated every 7 to 10 days if a significant rain event doesn’t occur. Flavor and fruit quality are increased when irrigation is gradually reduced during fruit maturation. Pomegranates are tolerant of some flooding, but sudden changes to irrigation amounts or timing may cause fruit to split.

Two pomegranate training systems: single trunk on the left and multi-trunk on the right. Photo Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, University of Florida/IFAS

Pomegranates establish best when planted in late winter or early spring (February – March). If you plan to grow them as a hedge (shrub form), space plants 6 to 9 feet apart to allow for suckers to fill the void between plants. If you plan to plant a single tree or a few trees then space the plants at least 15 feet apart. If a tree form is desired, then suckers will need to be removed frequently. Some fruit will need to be thinned each year to reduce the chances of branches breaking from heavy fruit weight.

Anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum sp. to pomegranate fruit. Photo Credit: Gary Vallad, University of Florida/IFAS

Anthracnose is the most common disease of pomegranates. Symptoms include small, circular, reddish-brown spots (0.25 inch diameter) on leaves, stems, flowers, and fruit. Copper fungicide applications can greatly reduce disease damage. Common insects include scales and mites. Sulfur dust can be used for mite control and horticultural oil can be used to control scales.

by Mary Salinas | Jul 11, 2019

Ripening thornless blackberries. Photo credit: Mary Salinas, UF/IFAS Extension.

To everyone’s delight, the blackberries are ripening in the Santa Rosa County Extension demonstration garden. The blackberry patch is a reliable perennial that continues to provide fresh berries year after year. Before you decide against them because you don’t want a thorny and painful hazard in your landscape, remember that there are thornless blackberry cultivars with fruit just as tasty as the old-fashioned thorny blackberry varieties. However, it is important to take care and make sure that the variety or cultivar you choose is adapted to our Florida climate and chill hours.

Blackberries bloom and produce fruit on last year’s canes. This year’s growth (the bright green shoot in the front center) will produce next year. Photo credit: Mary Salinas, UF/IFAS Extension.

You can choose a blackberry variety from your local nursery or propagate some plants from a favorite blackberry grown by a friend or neighbor (with permission, of course). Methods of propagation include stem cuttings, root cuttings, tip layering and removing the suckers that arise from the roots.

Plant when the weather is cooler in winter and choose a sunny spot with good soil. Frequent irrigation is crucial during the establishment period and when the fruit is produced. Weed control with organic or plastic mulches is also important to the success of your blackberry patch.

For more information on blackberry cultivars, propagation and growing success please see the University of Florida publication The Blackberry.

by Molly Jameson | Jun 25, 2019

Although blackberries are well adapted to North Florida, many different biotic and abiotic factors can impact fruit production. Photo by Molly Jameson.

Diagnosing Abiotic Blackberry Fruit Disorders

Whether it be wild blackberries you’ve foraged or a prized cultured variety you’ve oh-so-carefully sustained, we are now in prime blackberry season, and there are many sweet, tangy delectable fruits to be eaten.

Blackberry bushes are well adapted to the Florida Panhandle and the plants can be found growing all over – along roadways, in ditches, throughout open fields, and also within forests.

Although wild blackberries and domesticated cultivars thrive in our climate, there is a wide range of factors that could affect blackberry fruiting. When diagnosing plant problems, we tend to blame insects and diseases, but there are many abiotic (non-living) factors that could negatively impact blackberry fruit production. If your blackberry drupelets (the small subdivisions that comprise a blackberry fruit) are compromised, you may be experiencing one or more of the following abiotic blackberry disorders.

Although blackberries can self-pollinate, insect pollination is critical for forming the best blackberries. Photo by Johnny N. Dell, Bugwood.org.

Poor Pollination. Blackberries, strangely enough, are not true berries botanically. True berries only have one ovary per flower (such as bananas, watermelons, and avocados!). Each blackberry flower contains over 100 female flower parts, called pistils, that contain ovaries. To form a fully sized blackberry with many drupelets, at least 75% of the ovaries need to be pollinated. While blackberries can self-pollinate, pollinator insects, such as bees, are very important to ensure adequate drupelet formation. When weather conditions are overly cloudy and rainy, bees are less active. If this coincides with blackberry flowering, you may end up with some blackberries that are nearly drupe-less.

White Drupe. If you notice patches of white and brown drupelets on your most sun-exposed canes, you might have white drupe disorder. When humidity drops and temperature heats up, solar radiation contacting your berries is more powerful, as there is less moisture in the air to deflect the intense heat. Berries that are not protected by leaf coverage, and those on trellises oriented for maximum sun exposure, are most vulnerable to white drupe damage.

Sunscald. Often associated with white drupe, sunscald is most common when temperatures are extreme. Daytime highs in the Florida Panhandle in June and July regularly reach 90°F, if not higher. At these times, fruit exposed to the sun can be hotter than the air temperature around them, which essentially cooks the fruit. As I suspect you’d prefer to cook your fruit after harvest in preparation for blackberry pie, orient your trellis so it gets shade relief during the hottest part of the day and harvest often.

Diagnosing a blackberry issue can be challenging, as there can be more than one culprit impacting the fruit. Photo by Molly Jameson.

Red Cell Regression. One of the not-so-well understood abiotic blackberry disorders is red cell regression, or red drupelet disorder. If you’ve ever harvested blackberry fruit and stored them in the refrigerator for later munching, you may think your eyes are deceiving you when you discover your fruit doesn’t appear as ripe as when you picked it. This regression in color is linked to rapid temperature change, but rest assured, it does not affect the sugar content of the fruit. There are a few things you can do if you think this is affecting your berries, such as harvesting in the morning when the berries are still cool, harvesting when the sky is overcast, or shading your berries pre-harvest. You can also try to cool your berries in stages, perhaps moving from the field, to shade, to A/C, and then to the fridge.

Beyond abiotic stresses, blackberries can also suffer from insect, pest, and disease damage, such as from stink bugs, beetles, mites, birds, anthracnose, leaf rust, crown gall, and beyond. For domesticated blueberry bushes, proper cultivar selection, site selection, planting technique, fertilization, irrigation, propagation, and cane training is important and will allow the plants to grow healthy to defend themselves against any abiotic or biotic nuisance that comes their way.

For more information about growing blackberries, check out the EDIS publication, The Blackberry (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/hs104).

by Danielle S. Williams | May 20, 2019

Citrus leafminer injury. Photo: James Castner

Spring is in full swing and citrus trees have begun actively flushing. With the new flush comes an array of insect pests. One of the most common being the citrus leafminer. The citrus leafminer is a small white moth, about 2.4 mm in length. It is more easily detected during its larval stage by the serpentine larval mines it produces on the underside of citrus leaves.

Citrus leafminer adult. Photo: James Castner

The larvae of the citrus leafminer feed on the new growth or flush of citrus causing serpentine mines to form under the leaf cuticle. This can result in leaf curling and distortion. Citrus leafminer injury to foliage can stunt the growth of young trees and in areas where the citrus canker pathogen is present, provide an opening for infection.

Distortion and leaf curling caused by citrus leafminer. Photo: Danielle Sprague

The term ‘flush’ is commonly used to describe the new foliar growth between bud break and shoot expansion. Citrus trees usually have several flushes per year, depending upon cultivar, climate and crop load. Generally, most citrus cultivars in our area have around three flushes. The main flush is the spring flush in late winter/early spring. Following that, two additional flushes occur around the end of June and late September.

Citrus leafminer on young flush. Photo: Danielle Sprague

Adult leafminers require the new citrus flush for development. Eggs are laid within the flush. After two to ten days, the larvae emerge and feed causing the mines to occur. Larvae are protected within the leaf and therefore difficult to control. Pupation occurs within the leaf mine and takes anywhere from six to 22 days, depending upon temperature. Adults emerge around dawn and are most active in the morning and evening. In Florida, one generation of citrus leafminer is produced about every three weeks but populations increase when citrus trees are flushing.

In Florida, several natural enemies assist with reducing citrus leafminer populations. Studies have shown that predation from natural enemies can reduce leafminer populations by 90%. Primary predators of citrus leafminers include ants, lacewings and spiders. A parasitic wasp, Ageniaspis citricola was introduced into Florida and has become established. The parasitic wasp attacks the immature stages of citrus leafminer. Ageniaspis citricola can be requested and obtained for free from the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS). Because it is a specialized parasitoid of the citrus leafminer larval stage, it should be released only when mines start to become visible on flush.

Citrus leafminer can be difficult to control with insecticides due to the fact that they are within the leaf and protected. Applications of insecticides require proper timing and may require repeat applications. For a full list of insecticides, contact your local Extension Office.

For more information on citrus leafminer, use the links to the following publications:

Citrus Leafminer, Phyllocnistis citrella Stainton (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Phyllocnistinae)

Citrus Leafminer Control – UGA