by Sheila Dunning | Sep 7, 2019

“There are these weeds spreading all over my yard. They have little round leaves that are real close to the ground and creep in every direction. I keep trying to get rid of them by mowing my grass shorter, but they are killing my grass. What are they and how do I get rid of them?” Here at the Extension office, this is a conversation I have had nearly daily for the past month. We are here to help with identification and control of many landscape problems, including weeds.

However, my first word of advice is to change the mowing practice. Short, spreading weeds cannot be mowed out. You need to do just the opposite. Mowing as high as possible (3-4”) will help to reduce weeds by shading them out, therefore, reducing their spread.

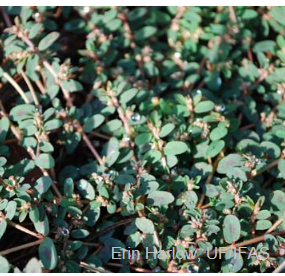

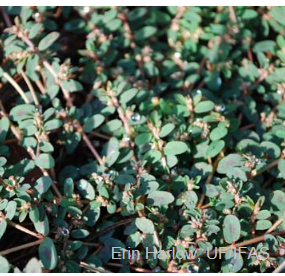

In every instance, the weeds have been common lespedeza (Kummerowia striata (Thunb.) Schind syn. Lespedeza striata) and/or prostrate spurge (Euphorbia maculata syn. Chamaesyce maculata). Both grow close to the ground with a spreading habit. Both have small, rounded leaves and produce small, light-colored flowers. But, if you look close, there are significant differences that will help with identification.

Common lespedeza, also known as Japanese clover, is prostrate summer annual that forms 15-18 inch patches. The stems are wiry. It has dark green trifoliate

Common lespedeza, also known as Japanese clover, is prostrate summer annual that forms 15-18 inch patches. The stems are wiry. It has dark green trifoliate  (arranged in threes) leaves with three oblong, smooth leaflets. Leaflets have parallel veins nearly at right angles to a prominent mid-vein. Its leaves have smooth edges and a short spur at the tip of each leaflet. Flowers appear in late summer with small pink to purple, single flowers found in leaf axils on most of the nodes of the main stems. As common lespedeza matures, the stems harden and become woody.

(arranged in threes) leaves with three oblong, smooth leaflets. Leaflets have parallel veins nearly at right angles to a prominent mid-vein. Its leaves have smooth edges and a short spur at the tip of each leaflet. Flowers appear in late summer with small pink to purple, single flowers found in leaf axils on most of the nodes of the main stems. As common lespedeza matures, the stems harden and become woody.

Prostrate spurge is a summer annual broadleaf weed that spreads by seed. The leaves are oval in shape, small, and opposite along the stem. As it matures, a red spot may form in the center of the leaf, earning it the common name spotted spurge. Another distinct characteristic is the stem contains a milky sap that oozes when the stem is broken. Light pink to white-colored flowers appear from early-summer through the fall.

Both are annual,broadleaf weeds, so there are several post-emergent herbicides available to kill the ones present. Don’t forget the pre-emergent herbicide application in late winter though. These weeds can drop plenty of seed. The importance of knowing which weed you have is more about the message they are trying to send you. These weeds can indicate other issues that may be part of the reason the grass is thinning and allowing the weeds to take over in the first place.

Common lespedeza is a legume. It thrives when water is plentiful and soil nutrients are low. If this is the weed “taking over” your yard, you need to get a soil test and evaluate your watering habits. Improving fertility and reducing soil moisture will naturally weaken common lespedeza.

If your thin patches of declining grass are being replaced with spurge, it may be time to submit a sample for a nematode assay. Research has shown that spurge is a weed that can thrive with high populations of nematodes. Turfgrass species are easily harmed by nematodes (microscopic roundworms that imbed into and on grass roots). If the assay indicates harmful population levels, unfortunately there are few options for reduction of the nematodes. However, several ornamental plants are tolerant. So, you may need to consider creating a landscape bed area rather than continuing to battle poor-looking grass.

Weeds can serve as indicators to soil conditions that may need to be addressed. Learning to identify weeds may teach you more than just their names.

by Matt Lollar | Sep 7, 2019

A couple weeks ago, I was on a site visit to check out some issues on Canary Island Date Palms. The account manager on the property requested a site visit because he thought the palms were infested with scale insects. He noticed the issue on a number of the properties he manages and he was concerned it was an epidemic. From a distance, lower fronds were yellowing from the outside in and the tips were necrotic. These are signs of potassium deficiency with possible magnesium deficiency mixed in.

Transitional leaf showing potassium deficiency (tip) and magnesium deficiency (base) symptoms. Photo Credit: T.K. Broschat, University of Florida/IFAS Extension

Nutrient deficiencies are slow to correct in palm trees. It’s much easier to prevent deficiencies from occurring by using a palm fertilizer that has the analysis 8N-2P2O5-12K2O+4Mg with micronutrients. Even if the palms are part of a landscape which includes turf and other plants that require additional nitrogen, it is best to use a palm fertilizer with the analysis previously listed over a radius at least 25 feet out from the palms. However, poor nutrition wasn’t the only problem with these palms.

Upon closer look, the leaflets were speckled with little bumps. Each bump had a little white tail. These are the fruiting structures of graphiola leaf spot also known as false smut.

Graphiola leaf spot (false smut) on a Canary Island Date Palm. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

Graphiola leaf spot is a fungal leaf disease caused by Graphiola phoenicis. Canary Island Date Palms are especially susceptible to this disease. Graphiola leaf spot is primarily an aesthetic issue and doesn’t cause much harm to the palms infected. In fact, the nutrient deficiencies observed in these palms are much more detrimental to their health.

Graphiola leaf spot affects the lower fronds first. If the diseased, lower fronds are not showing signs of nutrient deficiencies then they can be pruned off and removed from the site. All naturally fallen fronds should be removed from the site to reduce the likelihood of fungal spores being splashed onto the healthy, living fronds. A fungicide containing copper can be applied to help prevent the spread of the disease, but it will not cure the infected fronds. Palms can be a beautiful addition to the landscape and most diseases and abiotic disorders can be managed and prevented with proper pruning, correct fertilizer rates, and precise irrigation.

by Danielle S. Williams | Aug 22, 2019

Recently, I received a call about a garden not producing the way it used to. After speaking with the homeowner, I decided to take a visit to see what was going on. On my visit, I could see that the tomatoes were stunted, yellow and wilting, the squash plants were flowering but not setting fruit, and the okra was stunted. After digging up some of the sick plants and examining the roots, the problem was as clear as day…root-knot nematodes.

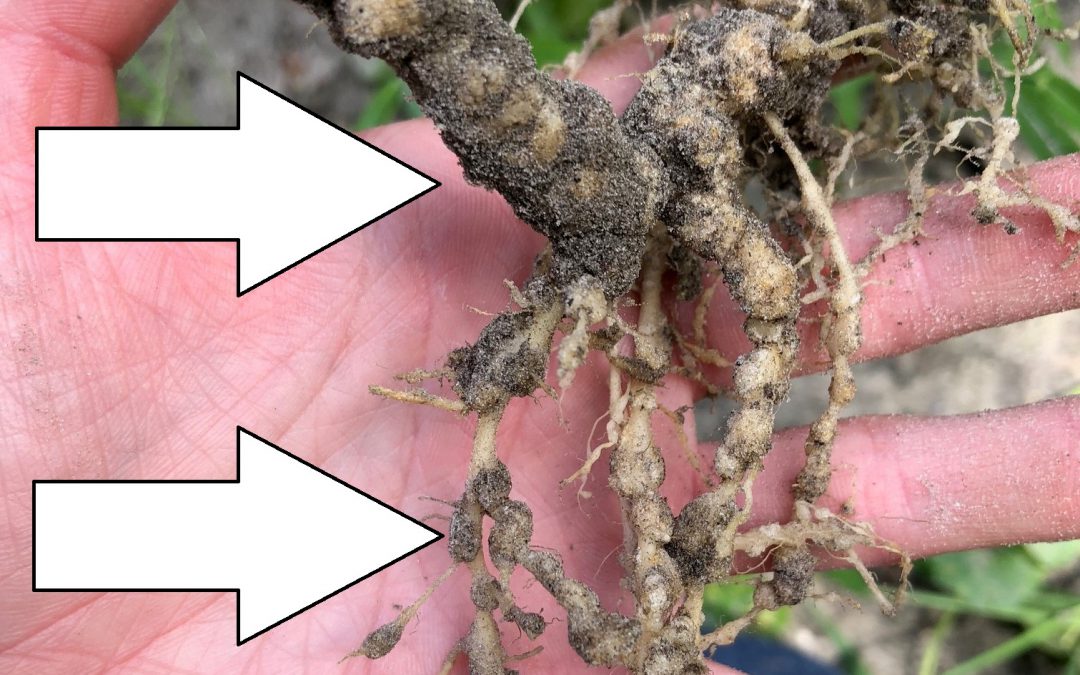

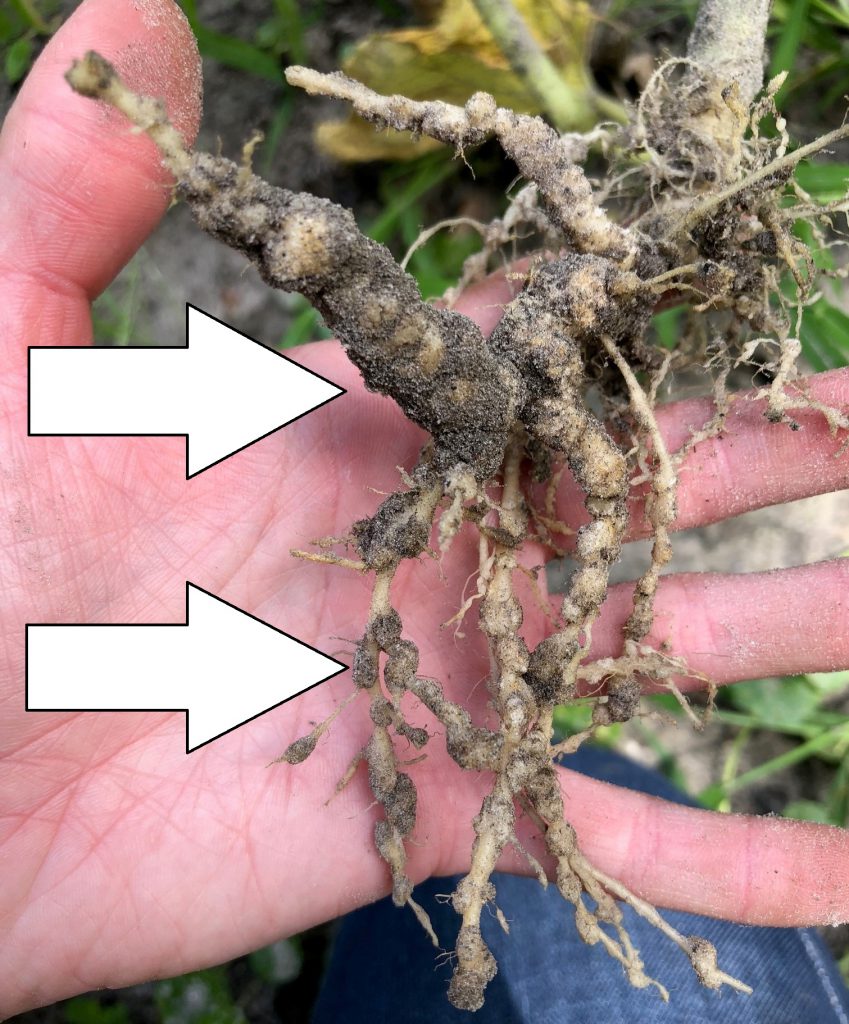

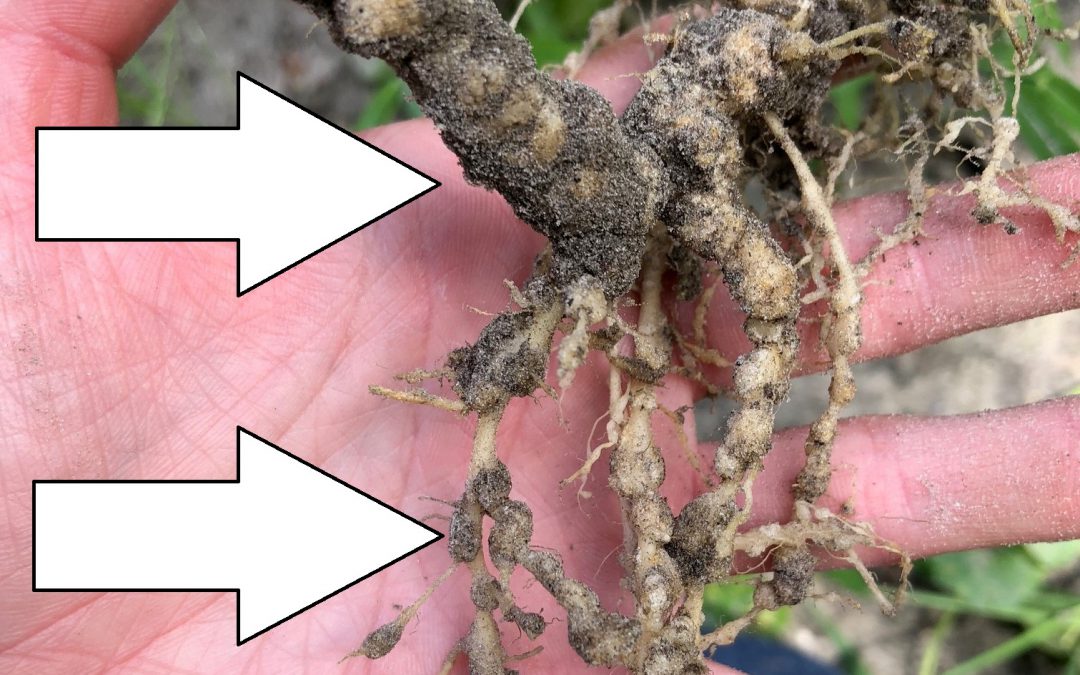

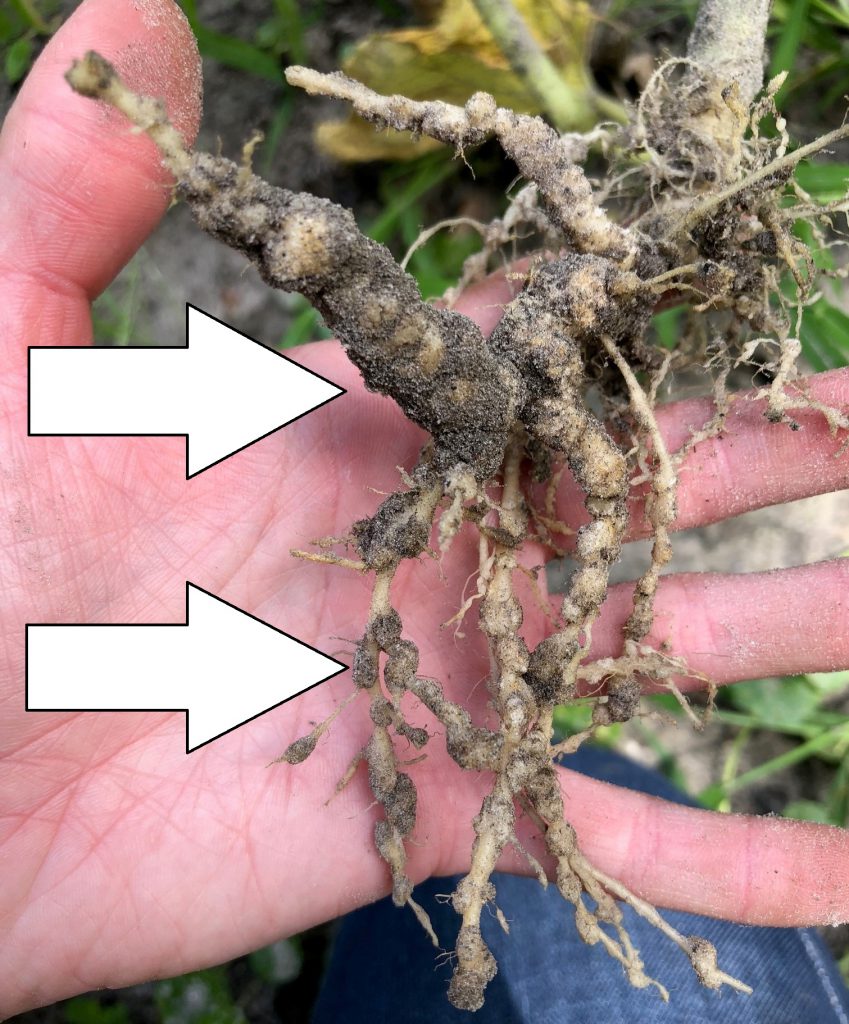

Galls on roots from root-knot nematodes

Root-knot nematodes are microscopic, unsegmented roundworms that live in the soil and feed on the roots of many common garden plants. Some of the most commonly damaged crops are tomatoes, potatoes, okra, beans, peppers, eggplants, peas, cucumbers, carrots, field peas, squash, and melons. Root-knot nematodes enter the root and feed, causing knots or galls to form. These galls are easily recognizable on the roots. If you’re inspecting the roots of beans or peas, be careful not to confuse nematode galls with the nitrogen-fixing nodules that are a normal part of the root system. As the nematodes feed, the root system of the plant becomes damaged and the plant is unable to take up water and nutrients from the soil. As a result, the plant may show symptoms of stunting, yellowing, and wilting.

What can I do about nematodes?

There are currently no nematicides labeled for use in the home garden but the best means of root-knot nematode management involves using a combination of strategies that make your garden less susceptible to attack.

Grow Resistant Varieties

Some varieties of crops are resistant to root-knot nematodes. This means is that a particular nematode can’t reproduce on the plant roots. When buying seed, read the variety label. The label may have ‘VFN’ written in capital letters. These letters indicate that the variety has resistance to certain diseases: V = Verticillium wilt; F = Fusarium wilt; and N = root-knot nematode. It’s best to use resistant varieties when root-knot nematodes are present.

Tomato plant showing signs of nematode damage – yellowing and wilting.

Sanitation

If you suspect you may have a nematode problem, be sure not to move soil or infected plant roots from an infected area to a clean area. Nematodes can easily be spread by garden tillers, hand tools, etc. so be sure to disinfect all equipment after use in problem areas.

Infected roots left in the soil can continue to harbor nematodes. After the crop is harvested, pull up the roots and get rid of them. Tilling the soil can kill nematodes by exposing them to sunlight.

Cover crops and Crop Rotation

Cover crops and crop rotation isn’t just a concept for farmers…gardeners need to implement the same practices! While this may take some planning, it is the most effective way to reduce pests and diseases.

Cover crops are crops that are not harvested and are typically planted between harvestable crops. They help improve soil quality, prevent soil erosion, and help control pests and diseases. Selecting cover crops that aren’t susceptible to root-knot nematode attack is key. When growing a cover crop that nematodes can’t reproduce on, populations should decline or not build up to begin with. Grain sorghum and millet can be planted as a summer cover crop and rye in the winter. French marigolds have been shown to reduce nematode populations as well.

Another simple way to manage root-knot nematodes is by crop rotation. Crop rotation is the practice of not growing crops that are susceptible to nematode attack, in the same spot for more than one year. Crops that aren’t susceptible to attack are cool season crops in the cabbage family such as broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, collards and kale.

Root-knot nematodes can wreck havoc on a garden so it’s important to take the necessary precautions to avoid them. It may require planning and patience but it will be worth it in the long run!

For more information on this topic, use the links to the following publications:

Nematode Management in the Vegetable Garden

Featured Creature: Nematodes

by Sheila Dunning | Aug 7, 2019

Damage caused by azalea lace bug, Stephanitis pyrioides (Scott), feeding. Photograph by James. L. Castner, University of Florida. Severely damaged leaves become heavily discolored and eventually dry or fall off. Symptoms may sometimes be confused with mite injury, but the presence of black varnish-like excrement, frequently with cast skins attached, suggest lace bug damage (Johnson and Lyon 1991).

You may be noticing the color disappearing from your azaleas right now. Do your azaleas look bleached out from a piercing-sucking insect. The culprit is probably azalea lace bug, Stephanitis pyrioides. This pest overwinters in eggs on the underside of infested leaves. Eggs hatch in late March and early April. The insect then passes through five nymphal instars before becoming an adult. It takes approximately one month for the insect to complete development from egg to adult and there are at least four generations per year. Valuable plants that are susceptible to lace bug damage should be inspected in the early spring for the presence of overwintering lace bug adults, eggs and newly-hatched nymphs. Inspect these plants every two weeks during the growing season for developing lace bug infestations.

Both adults and nymphs have piercing-sucking mouthparts and remove sap as they feed from the underside of the leaf. Lace bug damage to foliage detracts greatly from the plant’s beauty, reduces the plant’s ability to produce food, decreases plant vigor and causes the plant to be more susceptible to damage by other insects, diseases or unfavorable weather conditions. The azalea can become almost silver or bleached in appearance from the feeding lace bug damage.

However, lace bugs often go undetected until the infested plants show severe damage sometime into the summer. By then several generations of lace bugs have been weakening the plant. Inspecting early in the spring and simply washing them off the underside of the leaves can help to avoid damage later and the need for pesticides.

Adult lace bugs are flattened and rectangular in shape measuring 1/8 to 1/4 inch long. The area behind the head and the wing covers form a broadened, lace-like body covering. The wings are light amber to transparent in color. Lace bugs leave behind spiny black spots of frass (excrement).

Adult azalea lace bug, Stephanitis pyrioides (Scott), and excrement. Photograph by James. L. Castner, University of Florida.

Lace bug nymphs are flat and oval in shape with spines projecting from their bodies in all directions. A lace bug nymph goes through five growth stages (instars) before becoming an adult. At each stage the nymph sheds its skin (molts) and these old skins often remain attached to the lower surface of infested leaves.

Nymphs of the azalea lace bug, Stephanitis pyrioides (Scott), with several cast skins and excrement. Photograph by James. L. Castner, University of Florida.

Azalea lace bug eggs are football-shaped and are transparent to cream colored. Lace bug eggs are found on the lower leaf surface, usually alongside or inserted into a leaf vein. Adult females secrete a varnish-like substance over the eggs that hardens into a scab-like protective covering.

Other plant species, such as lantana and sycamore, may have similar symptoms. But, realize that lace bugs are host specific. They feed on their favorite plant and won’t go to another plant species. However, the life cycle is similar. Be sure to clean up all the damaged leaves. That’s where the eggs will remain for the winter. Start next spring egg-free.

For more information go to: http://entomology.ifas.ufl.edu/creatures/orn/shrubs/azalea_lace_bug.htm

by Mary Salinas | Oct 20, 2018

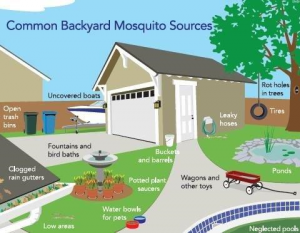

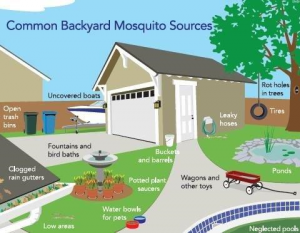

A natural disaster such as Hurricane Michael can cause excess standing water which leads nuisance mosquito populations to greatly increase. Floodwater mosquitoes lay their eggs in the moist soil. Amazingly, the eggs survive even when the soil dries out. When the eggs in soil once again have consistent moisture, they hatch! One female mosquito may lay up to 200 eggs per batch . Standing water should be reduced as mush as possible to prevent mosquitoes from developing.

You should protect yourself by using an insect repellant (following all label instructions) with any of these active ingredients or using one of the other strategies:

- DEET

- Picaridin

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus

- Para-menthane diol

- IR3535

- An alternative is to wear long-sleeved shirts and pants – although that’s tough in our hot weather

- Wear clothing that is pre-treated with permethrin or apply a permethrin product to your clothes, but not your skin!

- Avoid getting bitten while you sleep by choosing a place with air conditioning or screens on windows and doors or sleep under a mosquito bed net.

Now let’s talk about mosquito control in your own landscape.

Let’s first explore what kind of environment in your landscape and around your home is friendly to the proliferation of mosquitoes. Adult mosquitoes lay their eggs on or very near water that is still or stagnant. That is because the larvae live in the water but have to come to the surface regularly to breeze. The small delicate larvae need the water surface to be still in order to surface and breathe. Water that is continually moving or flowing inhibits mosquito populations.

Look around your home and landscape for these possible sites of still water that can be excellent mosquito breeding grounds:

- bird baths

- potted plant saucers

- pet dishes

- old tires

- ponds

- roof gutters

- tarps over boats or recreational vehicles

- rain barrels (screen mesh over the opening will prevent females from laying their eggs)

- bromeliads (they hold water in their central cup or leaf axils)

- any other structure that will hold even a small amount of water (I even had them on a heating mat in a greenhouse that had very shallow puddles of water!)

You may want to rid yourself of some of these sources of standing water or empty them every three to four days. What if you have bromeliads, a pond or some other standing water and you want to keep them and yet control mosquitoes? There is an environmentally responsible solution. Some bacteria, Bacillus thuringiensis ssp. israelensis or Bacillus sphaericus, only infects mosquitoes and other close relatives like gnats and blackflies and is harmless to all other organisms. Look for products on the market that contain this bacteria.

For more information:

Mosquito Repellents

UF/IFAS Mosquito Information Website

Common lespedeza, also known as Japanese clover, is prostrate summer annual that forms 15-18 inch patches. The stems are wiry. It has dark green trifoliate

Common lespedeza, also known as Japanese clover, is prostrate summer annual that forms 15-18 inch patches. The stems are wiry. It has dark green trifoliate  (arranged in threes) leaves with three oblong, smooth leaflets. Leaflets have parallel veins nearly at right angles to a prominent mid-vein. Its leaves have smooth edges and a short spur at the tip of each leaflet. Flowers appear in late summer with small pink to purple, single flowers found in leaf axils on most of the nodes of the main stems. As common lespedeza matures, the stems harden and become woody.

(arranged in threes) leaves with three oblong, smooth leaflets. Leaflets have parallel veins nearly at right angles to a prominent mid-vein. Its leaves have smooth edges and a short spur at the tip of each leaflet. Flowers appear in late summer with small pink to purple, single flowers found in leaf axils on most of the nodes of the main stems. As common lespedeza matures, the stems harden and become woody.