by Rick O'Connor | Feb 10, 2022

It is now mid-winter and much colder than our trip in January. During February’s hike the temperature was 44°F, compared to 62°F in January. It was overcast with a cold breeze from the northeast – again, colder. When conditions are like this I am not expecting to see much. If I did find something I would expect it to be one of our warm blood friends, mammals or birds, and even they would prefer a day with more sun and less breeze. But I came to see what was out roaming. So, a hike I made.

The Gulf front at Park East near Big Sabine.

This month I hiked the Big Sabine area east of Pensacola Beach. It began with a shore walk along the Gulf and then a transect across the different dune fields to the marshes and seagrasses along the Santa Rosa Sound.

There was no one out today. You could see footprints in the sand, and it had that characteristic “squeak” sound of fresh sand or snow. The only wildlife I saw on the Gulf side was a group of pelicans sitting on very calm water, obviously enjoying the morning. However, you could see footprints of mammals that had come earlier. There are raccoons, armadillos, mice, coyotes, and occasional reports of otters on Santa Rosa Island. There were a lot of skunks on the island prior to Hurricane Ivan (2004), but I have not seen any since. There have been reports of bears on the island as well. I have never seen one, nor their tracks, so do not think they are frequent visitors. I did find a dead shark tossed up on the beach by a fisherman. Not sure if they were trying to catch it or not.

A variety of mammals are found on barrier islands. Most move at night and you know they are there only by their tracks.

This small shark was found on the beach during the hike. I am not sure why they did not return it to the Gulf.

As I began my transect across the island I ventured into the secondary dune field, which during summer is extremely hot. This part of the island reminds me somewhat of a desert. Very dry, open, and at times very hot. Like the desert it comes alive more at night, but during winter you might see animal movement during the warm parts of the day. I did see mammalian tracks, which included humans and dogs.

This dune field also holds ephemeral ponds which can harbor a variety of life during the warmer months. Today I only found one blooming yellow-bladder wort as well as other carnivorous plants along the bank such as sundews and ground pines.

Yellow bladder wort is one of the small carnivorous plants that live on our barrier islands.

Sundews are another one of the small carnivorous plants found here.

From the open dune field, you venture into the tertiary dunes and the maritime forest. Trees grow here but their growth is stunted due to the salt content in the air. None the less, pine and oak hammocks liter this dune area providing great hiding places for wildlife. Though we did not see any today, I am expecting to find some as the weather warms.

The backside of the island is where you will find the salt marsh. This brackish wetland harbors its own community of creatures, which were not visible today but will be in the spring. Between the tertiary dunes and the marsh runs a section of the Florida Trail. Hikers can walk this section and observe wildlife from both ecosystems.

The larger dunes of the tertiary dune field.

Tree hammocks are common in the tertiary dune fields and provide good places for wildlife.

I eventually reached the Sound and the seagrass beds that exist there. Today, here was nothing really moving around, though I did find a dead jellyfish drifting in the waves. As the island wildlife tends to hideout the winter in burrows, the fish move to deeper water where it is warmer.

The backside of these large dunes drop quickly back to sea level.

Many plants in the tertiary dunes exhibit “wind sculpting”. It appears someone has taken a brush and “brushed” the tree towards the Sound.

Scat is another sign used to identify mammal activity in the dunes.

Portions of the Florida Trail cut through the tertiary dune field of Big Sabine.

The salt marsh

This holding pond is a remnant of an old fish hatchery from the late 1950s and is primarily freshwater.

Seagrass meadows can be found in Santa Rosa Sound and harbor a variety of marine life.

Jellyfish are common on both sides of the island. This one has washed ashore on Santa Rosa Sound.

There was little out today other than a few birds. We will see what late winter will expose next month.

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 3, 2022

Seahorses are one of the coolest creatures on this planet – period. I mean who doesn’t like seahorses? People state “I love snakes”, “I hate snakes”, “I love sharks”, “I hate sharks”. But no one says, “I hate seahorses”. They are sort of in the same boat with sea turtles, everyone loves sea turtles. They are an icon of the sea, logos for beach products and coastal HOAs, underwater cartoons and tourist development boards, diving clubs and local restaurants. But have you ever seen one? I mean beyond seeing one at a local aquarium or such, have you ever found one while snorkeling on one of our beaches?

Most would say no.

I have lived in the panhandle all my life and have spent much of it in the water, and I can count on both hands the number of times I have encountered a seahorse while at the beach. Most encounters have been while seining. I cannot count on both hands how many times I have pulled a seine net here but very few of them did a seahorse encounter occur. When they did, it was over grassbeds. In each encounter the animal was lying in the grass not wriggling like the other fish, just lying there. It would be very easy to miss them discarding it as “grass”. It makes you wonder how many times I captured one and did not know it. When we did find one it was VERY exciting. My students would often scream “I had NO idea they lived here!”.

The seahorse Photo: NOAA

However, if you tried searching for them while snorkeling, which I have, the encounter rate is zero. But this makes sense. These animals are so well camouflaged in the grass it would be a miracle to find one just hanging there. This is by necessity really. If you have ever watched a seahorse in an aquarium they are not very “fleet of foot”. Escaping a predator by dashing away is not one of their finer skills. No, they must blend in and remain motionless if trouble, like a snorkeler, comes by.

But I have seen one while diving. It was a night dive near the Bob Sikes Bridge on Pensacola Beach about 40 years ago. We were exploring when my light swung over to see this large seahorse extended from a pipe that was coming out of some debris on the bottom. I was jubilated and screamed, as best you can while using SCUBA, for my partners to come check this out. We were all amazed and my interest in these animals increased.

When I attended Dauphin Island Sea Lab (DISL) as an undergraduate student, like many in the 1970s, I thought I would get involved with sharks, but I quickly developed a love for estuaries and my interest in seahorses returned. I made a visit to the library there and found very little in the literature, at that time, which piqued my interest even more. My senior year we had to complete a project where we had to collect, and correctly identify, 80 species of fish to pass the class. I asked the crew of the research vessel at DISL if they had ever found seahorses. They responded yes and took me to what they called their “seahorse spot”. We caught some. It was very cool. And yes… seahorses do exist here in the wild.

But what is this amazing animal?

What do I mean by this? As a marine science instructor, I would give my students what are called a lab practical’s. Assorted marine organisms would be scattered around the room and the students had to give their common name, phylum name, class name, and answer some natural history question I would ask. Snails are mollusk, mackerel are fish, jellyfish are cnidarians, and then they would come to the seahorse. Seahorses were… well… seahorses! What the heck are they?

Many of you may know they are fish. But over the years of teaching marine science, I found that many students were not sure of that. The definition of a fish is an animal with a backbone that possesses a scaly body, paired fins (usually), and gills. Seahorses have all that. There is a backbone no doubt. The scales are not as obvious because they are actually fused together in a sort of armor. The paired fins and gills are there. Yep… they are fish, but a fish (horse) of a different color.

This seahorse is a species from Indonesia.

Photo: California Sea Grant.

First, they are one of about 13 families of fish in the Gulf of Mexico that lack ventral fins, those on the belly side of their bodies. Second, they lack a caudal fin (the fish tail) and have a more prehensile tail for grabbing objects. Third, they swim vertically instead of horizontally as most fish do. Again, there is nothing about their body design that says “speed”.

Another thing I find fascinating about these animals is their global distribution. You might recall that the initial focus of this series on Florida panhandle vertebrates was the biogeography of these creatures. Seahorses are found all over the world. There are over 350 species of them. But the interesting question is: how would a seahorse living in the northern Gulf of Mexico reach Melbourne Australia? It makes sense that being so far apart there would be such differences in looks and genetics that they would be classified as different species, but how did an animal like a seahorse disperse across a large ocean like the Pacific?

Honestly, I can say the same for ghost crabs, which I found on the beaches of Hawaii. How did they get there? But that is another story.

My best guess was the dispersal occurred at a time when the two continents were closer together. The Pangea days, or some time close to that period. And as the continents “drifted” the seahorses remained close to their shorelines and moved apart. They may have been able to “island hop” across coral reefs to other Indonesian Islands, but those here in the United States were long lost relatives that changed in their appearance and lifestyles due to the large separation from others. That is my two cents anyway.

Hoese and Moore1 list two species of seahorses found here in the northern Gulf of Mexico. The Lined Seahorse and the Dwarf Seahorse.

The Lined Seahorse (Hippocampus erectus) is the larger of the two, reaching an average length of five inches. This is the one I found near the Bob Sikes Bridge all those years ago. Like all seahorses they are well adapted to life in debris where they can grab on to something with their prehensile tail and feed on small zooplankton using their vacuum like tube snout. Like all seahorses, the males have a brood pouch that holds the fertilized eggs producing live birth – another “live bearer”. They are usually dark in color, but gold individuals have been reported. Some have filamentous threads on their bodies making them look even more like plants. Their biogeographic distribution is amazing. They are found from Nova Scotia, throughout the tropics, all the way to Argentina. This suggests few biogeographic barriers, other than substrate to hide in.

The Dwarf Seahorse (Hippocampus zosterae) – also known as the pygmy seahorse – is much smaller, with a mean length of 1.5 inches. That would qualify as “dwarf” or “pygmy”. How would you ever find these? Other than size, the difference between these two are the number of rays (soft spines) in their fins. They can be counted, but its not fun, especially with a 1.5” seahorse. This guy prefers high salinity, actually, I have found that most seahorses do. This one is more tropical in distribution.

There is a third Florida species, the long snout seahorse (Hippocampus redi) that is found on the Atlantic coast, but not in the Gulf.

The strange thing about the seahorses in Florida, has been the declining encounters over the last few decades. For a creature that seems to have few barriers, they have found trouble somewhere. Maybe the loss of habitat, maybe a population crash due to the common practice years ago of capture and drying out for tourists to buy. It could be a change in environmental conditions such as salinity in the Pensacola Bay area. I am not sure. The more I write this article, the more my interest in this fish returns. As many researchers and wildlife managers have mentioned, this is an animal who has “fallen through the cracks”. People notice the changes in sea turtle and manatee encounters, but not seahorses. Maybe it is time we pay more attention to them and see how they are doing. I for one would hate to see the decline of this creature here in the panhandle.

Reference

Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station, TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 17, 2021

Recently I watched a documentary on TV entitled The Loneliest Whale; the search for 52. The title grabbed my attention and so, I checked it out.

There are many forms of wildlife that are very hard to find in our area. But we continue to look.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Seems a decade or so ago the U.S. Navy was doing SONAR work in the Pacific between Washington and Alaska and detected a strange sound coming in at 52 hertz. They had not herd this before and would continue to hear it in different locations around the northern Pacific. Their first concern was it was something new from the Russians, but when they showed the graphs and played the recording to a marine mammologist named Dr. Watkins, they found that it was most likely a “biological” – mostly likely a whale.

The problem was that Dr. Watkins had never heard whales calling at 52 hertz. If it was a whale, it was calling a lot – but no other whales were answering. Hence the name “the loneliest whale”. If it was a whale, and no others would talk to it, it was kind of sad. But who was this whale? What kind was it?

Word of the loneliest whale spread around the world and many humans made a connection to this animal, possibly because of their own disconnect with their own species. Stories and ballads were written, and people began to feel for the poor animal that apparently had no friends.

This story caught the attention of a documentary film maker who was interested in finding “52”, as the whale became known. He solicited the help of other marine mammologists; Dr. Watkins had died. According to those marine mammologists, this was going to be VERY difficult. It is hard enough to find just a pod of whales in the open Pacific, much less a specific pod with a specific individual. But they were excited about the challenge of finding this one animal, “52”, and off they went.

As I was watching this documentary it reminded me of my own search here near Pensacola. In 2005, I was asked by members of state turtle groups if I could search to see if diamondback terrapins lived in the western panhandle. This turtle’s range is from Cape Cod Massachusetts to Brownsville Texas, but there were no records from the Florida panhandle. Did the animal exist there? I was running the marine science program at Washington High School at the time and thought this would be a good project for us. So, we began.

Mississippi Diamondback Terrapin (photo: Molly O’Connor)

This small turtle can be held safely by grabbing it near the bridge area on each side.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The students researched terrapin biology and ecology to determine the locations with the highest probability of finding, and we searched. I quickly found that the best time to search for terrapins was during nesting in May and June, and that the worst time to do a project with high school seniors was May and June. So, the project fell on my wife and me. For two years we searched all the “good spots” and found nothing. We placed “Wanted Poster’s” at boat ramps near the good spots with only calls about other species of turtles, not the terrapin.

Then one day in a call came in from a construction worker. Said he had seen the turtle we were looking for. For over a year we had been chasing “false calls” of terrapins. So, I was not overly excited thinking this would be another box turtle or slider. I asked a few questions about what he was looking at and he responded with “you’re the guy who put the wanted poster up correct? – well your turtle is standing next to the poster… it’s the same turtle”. Now I was excited. We did some surveys in that area and in 2007 saw our first terrapin! I can’t tell you how exciting it was. Two years of searching… at times thinking we might work on another project with a different species that actually exists… reading that the diamondback terrapin is like the Loch Ness monster – everyone talks about them, but no one has ever seen one. And there it was, a track in the sand and a head in the water. Yes Virginia… terrapins do exist in the Florida panhandle. The excitement of finding one was indescribable.

We were hooked. We now had to look in other counties in the panhandle, and yes, we found them. As I watched the program of the marine mammologists searching for “52” I could completely relate.

Today, as a marine educator with Florida Sea Grant, I train others how to do terrapin surveys and searches. I let them know how hard it is to find them and to not get disappointed. When they do see one, it will be a very exciting and fulfilling day. Our citizen science program has expanded to searching for other elusive creatures in our bay area. Bay scallops, which are all but gone however we do find evidence of their existence and spend time each year searching for them. In the five years we have been searching we have found only one live scallop, but we are sure they are there. We find their cleaned shells on public boat ramps – by the way, it is illegal to harvest bay scallops in the Pensacola Bay area. Another we are searching for is the nesting beaches of the horseshoe crabs. This is another animal that basically disappeared from our waters but are occasionally seen now. It is exciting to find one, but we are still after their nesting beaches and the chase is on.

Bay Scallop Argopecten irradians

http://myfwc.com/fishing/saltwater/recreational/bay-scallops/

Horseshoe crabs breeding on the beach.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

I love the challenge of searching for such creatures. If you do as well, we have a citizen science program that does so. You can just contact me at the Escambia County Extension Office to get on the training list, trainings occur in March, and we will get you out there searching. As for whether they found “52”, you will have to watch the program 😊

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 17, 2021

This is another one of those fish in this series that is not often seen but when you do see one you will ask “what is that?” – So, we will answer the question by including it here.

Like the frogfish we have already written about, batfish are described by Hoese and Moore1 as “grotesque” and they take it a step further by telling us all “ugly” fish (as they say) are grouped into what many call “dogfish”. As with the frogfish, I am not sure I would use the term grotesque, but they are strange looking.

Juvenile Polka-Dot Batfish (Ogcocephalus radiatus) in the polluted intracoastal waterway in Palm Beach County, FL.

Photo: Science Photo Library

I have only seen a couple in my life. Hoese and Moore mention they are often brought up in shrimp trawls, and I have seen them while doing trawl surveys at Dauphin Island Sea Lab. I also found one while snorkeling along a seawall near Gulf Breeze FL. So, they are out there just not encountered as often, or as well known, or seen as frequently, as many other fish in the Gulf. Another reason to include this group here.

It is hard to describe what this fish looks like. They are, as they say, dorso-ventrally flattened – meaning from top to bottom, not side to side – like a stingray. They have two fins extending from parts of their body that sort of “stick out of the side” and appear to be like webbed feet with which they walk. Actually, there are these small, modified fins on the ventral side that are used to walk on the bottom – they are bottom dwelling (benthic) fish for sure. Like their relatives the frogfish they have a modified spine that is used like a fishing lure. Like the frogfish, the shape of that lure can be used to identify species. But unlike the frogfish the lure is located between their mouth (which near the bottom of the body and is very small) and a pointed rostrum that extends from the top of their head like a battering ram. This lure is extended to lure not fish swimming above, as with the frogfish, but small creatures in and on the sand. Because of this they do not call the lure an illicium but a esca. These are strange looking fish.

Hoese and Moore list four different species and indicate there are at least three others in the Gulf of Mexico. Most are associated with the continental shelf of the Gulf and not inland where we might see them snorkeling around. A couple of species are more associated the continental slope, which drops from the continental shelf to the deep sea. But the Polka-dot batfish (Ogocephalus cubifrons) is reported as being inshore and is the species I have encountered.

Many species are only described as being from the shelf of the Gulf of Mexico and no other oceans. Some of them are even more restricted to either the eastern or western Gulf. This all suggests that batfish do have biogeographic barriers of some sort restricting their dispersal. Being offshore benthic fish, your first guess would be substrate. Usually in those locations the temperature and salinities are pretty similar but the material on the bottom (rock, shell, sand, canyons, etc.) are not. However, several articles mention that batfish can be found over rocky or sandy bottom2,3,4 and the polka-dot batfish can be found in grassbeds as well2. So, I am not sure what the possible barrier is, but several do have a limited range. The east-west split could very well be the DeSoto Canyon off the coast of Pensacola.

All of that said, it is a very interesting group of fish that for one species you might encounter while out and about snorkeling or diving in the Florida panhandle.

References

1 Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station, TX. Pp. 327.

2 Ogocephalus cubifrons, Polka-dot batfish. 2017. Discover Fishes. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/ogcocephalus-cubifrons/.

3 The Red-lipped Batfish. 2014. Ashland Vertebrate Biology. Ashland University, Ohio. http://ashlandvertbio.blogspot.com/2014/12/the-red-lipped-batfish.html.

4 Cocos Batfish, Ogocephalus porrectus. 2015. Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. https://biogeodb.stri.si.edu/sftep/en/thefishes/species/777.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 10, 2021

Most people would agree that this is one of the best times of the year. Christmas brings great music, great cooking, great family gatherings, and… great lights. The lighting of Christmas is one of the more beautiful parts of these celebrations and as I thought about Christmas and writing about nature I thought of those lights.

There is nothing like Christmas lights on a tree.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Nature can produce beautiful lights as well. Mostly found in the ocean – “phosphorus”, as many called it when I was growing up here, is a beautiful spectacle. It is hard to see with our artificial lights but in the warmer months of summer at locations far from the artificial lights of people, the sea glows a blue-green color that is amazing. Many see this light as sparkles in the water as the waves roll by. Others see it as a stream of light as a fish, or something else, moves around. In the right conditions, you can see your footprints glow as you step in the wet sand. I remember diving at night under the Bob Sikes Bridge once in the 1970s when the bridge, and all of the divers, were aglow. It was beautiful. This phenomena have amazed scientists for centuries and trying to understand how it is produced was a quest for many.

The term phosphorescence actually means using light to emit light. Turns out that is not what is happening in this case. Scientists found that some creatures posses a group of molecules known as luciferins. The term lucifer means “producing light” or “morning star” and seemed an appropriate name for this group of molecules. When luciferin is oxidized, the transfer of an electron emits a “cool light” – usually blue-green in color. Cool meaning that less than 20% of the emitted light is lost as heat. There is a catalytic enzyme known as luciferase that can increase the speed of this chemical reaction and produce bright light in seconds. Since this light is produced by a chemical reaction it was called “chemiluminescence”. However, since this reaction is produced and controlled by living organisms is more widely known as “bioluminescence”. It is not phosphorescence.

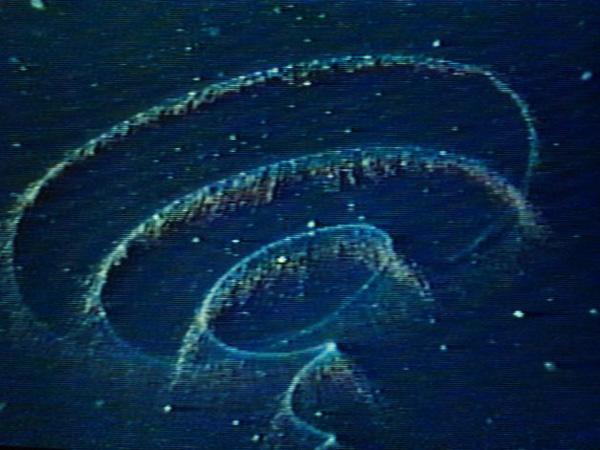

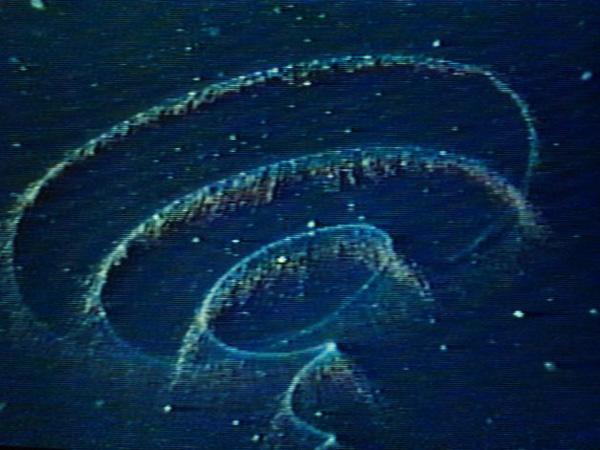

Bioluminescence in the sea.

Photo: North Carolina Sea Grant

There are many creatures that produce bioluminescence. The famous fireflies are one, but most live in the sea. The “phosphorus” we are used to seeing is produced by small single celled plants in a group known as dinoflagellates. When disturbed they emit blue-green light as a flash and then a slow dim. Fish swimming past, waves crashing on the beach, or boat and propeller pushing through the water will disturb them. The warmer the sea, the more dinoflagellates there are, the more amazing the light show is. There are lagoons in the tropical parts of the world where these small plants are trapped due to a small opening in and out of the lagoon. The entire lagoon can light up when the conditions are right.

Noctiluca are one of the dinoflagellates that produce bioluminescence.

Photo: University of New Hampshire.

But it does not stop with dinoflagellates. As you descend into the deep ocean the bioluminescence becomes even more spectacular. All sorts of creatures from jellyfish to squid, to fish, to even fungus and bacteria illuminate. Some species of luminescent marine animals do not produce the light themselves but rather harbor luminescent bacteria on the skin or specially designed skim pockets to hold them. Though blue-green is the dominant color, yellows, oranges, and reds have been produced. It has been suggested that blue-green is much easier to see in the deep so reds and oranges are less likely. That said, it is believed that some marine creatures will produce those colors to assist in capturing prey. They can see the red light, but their prey cannot.

The magical lights of the deep sea.

Photo: NOAA

Either way the illumination of the ocean, like the Christmas illumination of our streets and homes, is beautiful and amazing thing. As you admire the lights on the neighborhood home, find some short videos of bioluminescence online and enjoy the show. Happy Holidays everyone.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 10, 2021

Hoese and Moore1 describes members of the frogfish family as “grotesque”. Well… maybe. I am not sure I would call them grotesque, but they are sort of gelatinous blobs with reduced or missing scales. They feel sort of “mushy”. They have broad shaped fins and a free dorsal spine that serves as a “fishing rod and lure” called the illicium. Maybe they are a little grotesque…maybe.

Being round with broad fins, this is a very slow swimming fish, if you can call how they move swimming. So, to survive, they must blend in with the environment to avoid predators and wait for their prey to come within range before pouncing on them. The illicium lures prey to within range and their “gulp” is like a vacuum cleaner sucking food out of the water.

The family name for the group is Antennariidae, which is appropriate being they have that fishing lure, and is one of the few fish families whose gill opens are behind the pectoral fin. There are 48 species of frogfish found worldwide and most are tropical and subtropical2. Hoese and Moore1 indicate there are three species found in the Gulf of Mexico and all three can be found along the Florida panhandle.

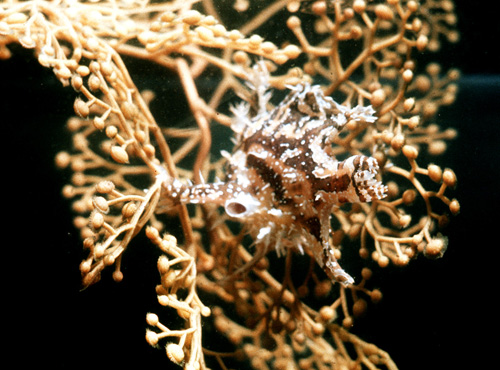

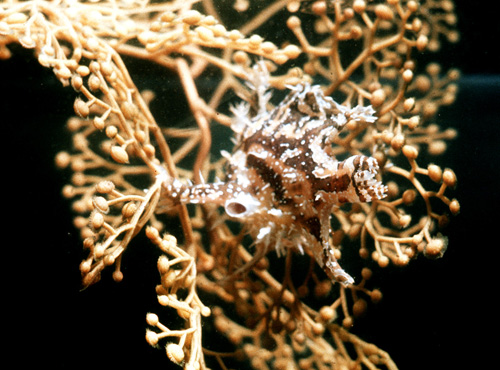

The most commonly encountered frogfish in our area is the Sargassum fish (Histro histro). This small six-inch fish blends in perfectly with the sargassum mats that float in close to shore. Using its fins to brace itself in the seaweed, this fish uses its illicium to attract a variety of small prey that live in the sargassum community. As the sargassum mats are blown close to shore the sargassum fish will leave and move to another mat further out. Finding them on the beach is rare but snorkeling out to a mat just offshore with a small hand net, you might be able to find one by scooping up some sargassum and taking a look.

This sargassum fish is well camelflouged within this mat of sargassum weed.

Photo: Florda Museum of Natural History

The Singlespot Frogfish (Antennarius radiosus) is even smaller at three inches and is found on hard habitats of the middle continental shelf offshore, but occasionally is found along the coastline.

The Splitlure Frogfish (Phrynelox scaber) is five inches in length and not as common on our shelf as the singlespot frogfish. Those that have been found off our coast were further offshore.

The Florida Museum of Natural History includes the Striated Frogfish (Antennarius striatus) as a Gulf species and resident of panhandle waters3.

The distribution of this group is pretty wide throughout the tropical and subtropical waters of the Atlantic Ocean and beyond – suggesting few geographic barriers to dispersal. The sargassum fish, of course, is restricted where sargassum is found – but sargassum is found in a lot of places. The singlespot frogfish seems to have a more restricted home range found in Bermuda, the Atlantic coast of Georgia and Florida, and the Gulf of Mexico. Hoese and Moore does not report this fish in other parts of the Caribbean as the others are1.

They may be grotesque to some, but to others it is an amazing group of fish, much fun in an aquarium, and exciting to find when snorkeling or diving.

1 Hoese H.D., Moore R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M University. College Station TX. Pp. 327.

2 Family Antennariidae – Frogfish. 2012. FishBase. https://www.fishbase.de/summary/FamilySummary.php?ID=192.

3 Antennarius striatus. 2017. Discover Fishes. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/antennarius-striatus/.