by Rick O'Connor | Jan 6, 2022

During 2022 I plan to make weekly hikes on Pensacola Beach to see what sort of wildlife, or other natural phenomena, I encounter each month. For the first January trip I did a short hike at Ft. Pickens on the west end of Santa Rosa Island.

Ft. Pickens is more wooded than much of the island and provides both maritime forest and beach habitats for a variety of wildlife. On my first trip – Jan 6 – the temperature was 62°F and overcast. It actually rained some during the hike. As I approached the fort area, I saw a bald eagle sitting on a sand dune.

A bald eagle sitting on a dune near Pensacola Beach.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Everyone gets excited about seeing a bald eagle. Its like dolphins, no matter how many times you see them, it is still cool, and you alert everyone they are there. The difference with bald eagles is that they were not always here. Growing up in Pensacola I rarely saw one. I worked for a period of time on what were called “the ponds” on the property of Air Products in Pace, Florida. The ponds were a water treatment system to help improve water quality coming from the plant being discharged into Escambia Bay. It was a wildlife sanctuary and there was plenty of wildlife there. Cottonmouths, deer, turtles, raccoons, and alligators were all common. One of the largest eastern diamondback rattlesnakes I have ever seen was found there. And, during the winter months, we would occasionally get a bald eagle. It was rare and very exciting.

A field guide of Birds of the Eastern United States published by Roger Tory Peterson in 1980 indicates that their winter breeding range includes much of Florida. A document published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife suggest they begin building nests in our area in September, lay eggs by October, and hatching occurs in November. Between November and March, the parents take care of them until the fledge and head out on their own. The reason we have not seen more in our younger years was their population was down. The decline of the national bird was due to a variety of reasons, but the DDT story played a role.

Today their numbers have rebounded and encounters with them in our area have increased. Their nest can be quite large and are usually close to a water source. These birds are known as predators but actually spend a lot of time feeding on carrion and robbing other birds of their food source. Competition between the osprey, another recovering species, and bald eagles are quite famous. And, like I said, you never get tired of seeing them. This time of year, you can spot them in several locations around the beach areas.

Other creatures found on this January hike at Ft. Pickens included:

Great blue herons use tall pines for nesting during winter.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Mockingbirds are quite common in the winter. This one was feeding on the red berries of a yaupon holly.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

This green blob is actually a sea slug known as a sea hare. It was returned to the water.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

This structure is often found on panhandle beaches. It is the egg case of the snail known as the moon snail. Also called the “shark’s eye” or “cat’s eye”.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Unfortunately dead seabirds on the beach are not uncommon. This one is a pelican.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

I encourage to take some time this winter and go for a hike and see what you can discover.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 6, 2022

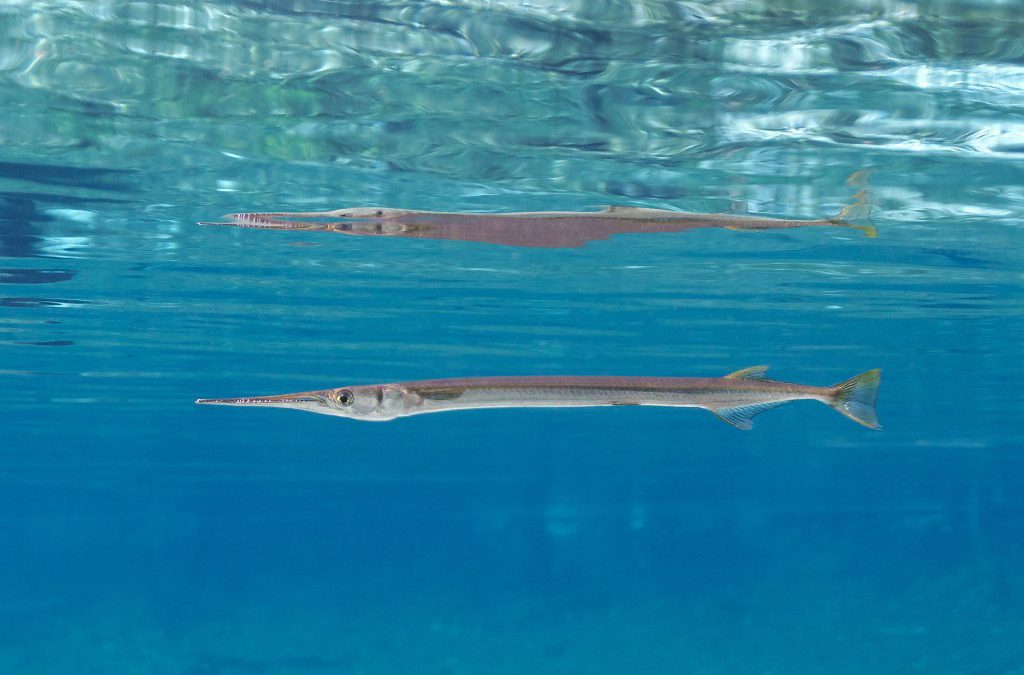

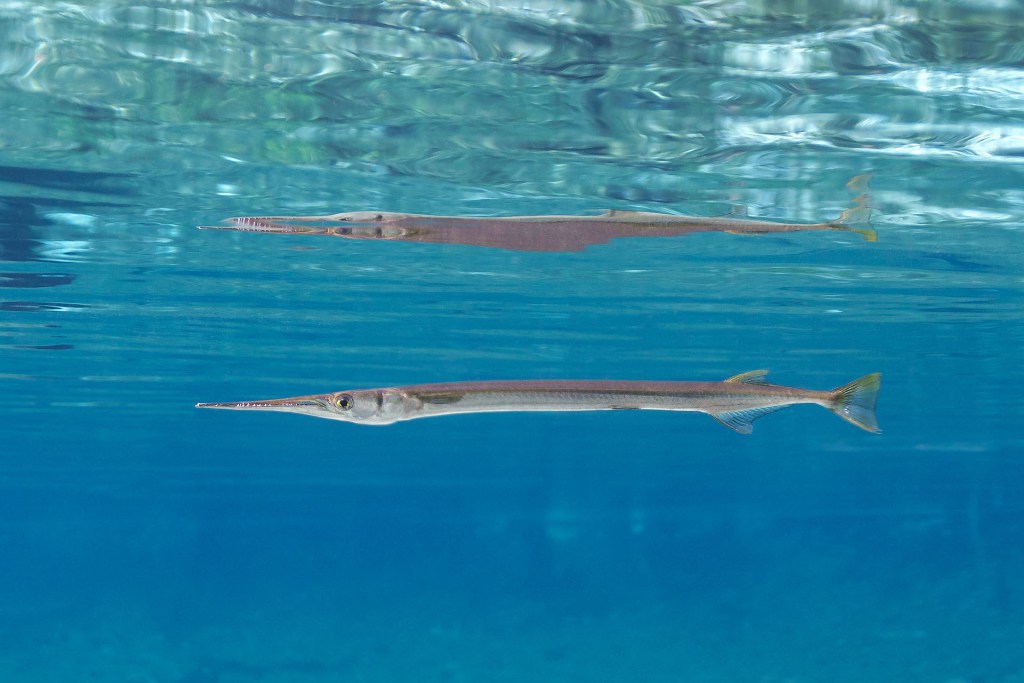

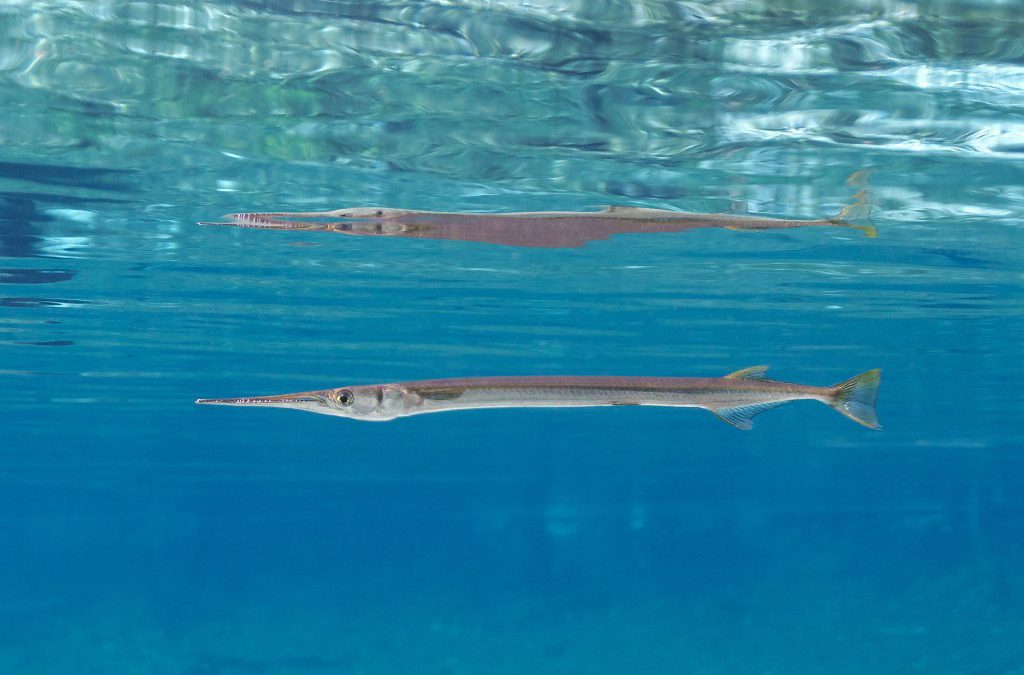

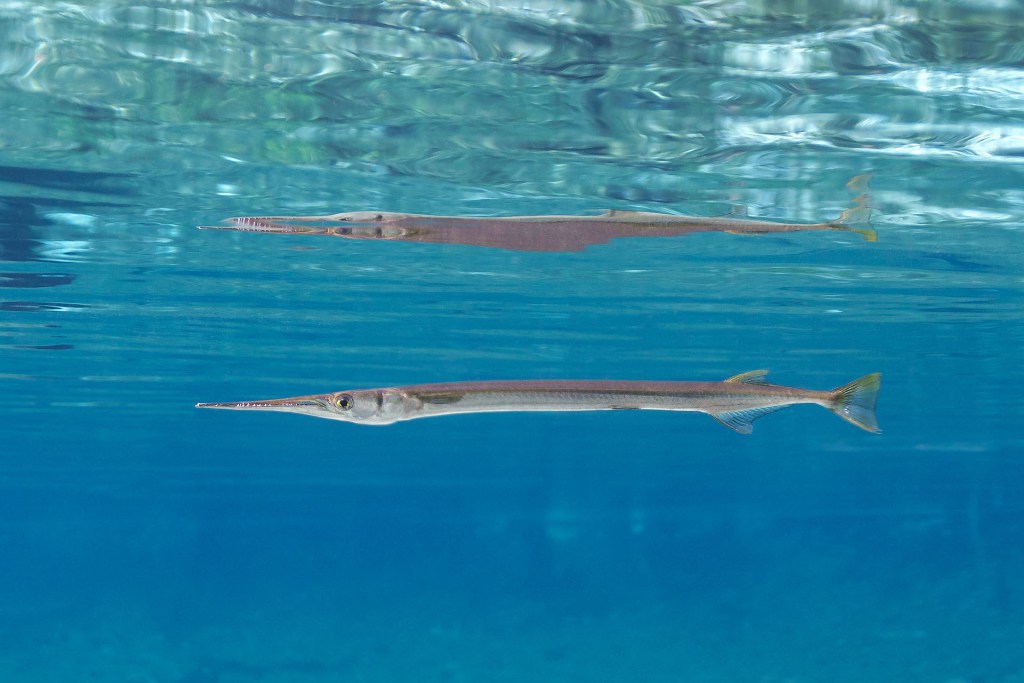

I remember first seeing a needlefish as a young boy on Pensacola Beach. We were either playing or snorkeling in Santa Rosa Sound and one of these long, sleek, “barracuda” looking fish swam by cruising the surface of the water. Your first reaction is danger. They have long jaws with very sharp teeth and move very “predator-like” through the water. Your fear is that if you get too close, they will turn and attack. I remember following them for several minutes watching how they looked at me but continued to search for prey. I was never attacked.

The Atlantic needlefish.

Photo: U.S. Geological Survey

Years later, as a marine science teacher, we were conducting a diversity and abundance study of nearshore fishes of the Pensacola Bay area. We would often catch these in our seine nets, and they would often get their numerous teeth snagged in the net. It took a careful maneuvering to remove them but in doing so, we could see their “nasty” side. They would try to bite, and bitten I was a few times. The needle like teeth did hurt a little and always drew blood. But once released they never turned on us, nor did the needlefish that were in the net and not snagged. We simply just released them.

I have often been asked by students “what do they eat?”. I have never read about, nor conducted a study, on their diet but would guess they prey on small fishes. Needlefish themselves are not terribly large, two feet being reported as the average length, so their prey could not be very large. Their long skinny snout and relatively small mouth with the lack of molars would suggest they must grab and swallow, almost whole, whatever lunch would be for that day. Fish that are only a few inches long at most. I have heard silversides, and killifish are popular targets for them, I can see this. I have seen them hunt in small groups, but mainly I see them alone. They themselves would be prey for larger predatory fishes in the bay area and birds, such as osprey, would hunt them due to their habitat of hunting at, or near, the surface.

Swimming near the surface is a common place to find needlefish.

Photo: Florida Springs Institute

Though Hoese and Moore1 report four species in our area, it is the Atlantic Needlefish (Strongylura marina) that I caught most often. Honestly, it is very hard to tell the species apart just by looking at them. One, the Keeltail Needlefish (Platybelone argalus) lacks gill rakers, if you know what those are, and this cannot be determined unless you catch the fish and take a peek. That said, I did capture these while conducting that fish diversity study with my marine science class. Like the Atlantic Needlefish, the Flat Needlefish (Ablennes hians) and the Houndfish (Tylosurus crocodilus) – you have to love that name “crocodilus” – have gill rakers and are differentiated by the number of rays on their anal fins. Another feature not easily noticed while snorkeling with them. I have heard the Houndfish can be aggressive. Hoese and Moore report they are more common offshore. We did capture one in Pensacola Bay and did not notice a “nastier” attitude.

All four species have a wide geographic range; found along the Atlantic coast, throughout the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, south to Brazil.

They are a common and interesting fish to see, and not dangerous as they may appear.

Reference

1 Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station, TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 17, 2021

This is another one of those fish in this series that is not often seen but when you do see one you will ask “what is that?” – So, we will answer the question by including it here.

Like the frogfish we have already written about, batfish are described by Hoese and Moore1 as “grotesque” and they take it a step further by telling us all “ugly” fish (as they say) are grouped into what many call “dogfish”. As with the frogfish, I am not sure I would use the term grotesque, but they are strange looking.

Juvenile Polka-Dot Batfish (Ogcocephalus radiatus) in the polluted intracoastal waterway in Palm Beach County, FL.

Photo: Science Photo Library

I have only seen a couple in my life. Hoese and Moore mention they are often brought up in shrimp trawls, and I have seen them while doing trawl surveys at Dauphin Island Sea Lab. I also found one while snorkeling along a seawall near Gulf Breeze FL. So, they are out there just not encountered as often, or as well known, or seen as frequently, as many other fish in the Gulf. Another reason to include this group here.

It is hard to describe what this fish looks like. They are, as they say, dorso-ventrally flattened – meaning from top to bottom, not side to side – like a stingray. They have two fins extending from parts of their body that sort of “stick out of the side” and appear to be like webbed feet with which they walk. Actually, there are these small, modified fins on the ventral side that are used to walk on the bottom – they are bottom dwelling (benthic) fish for sure. Like their relatives the frogfish they have a modified spine that is used like a fishing lure. Like the frogfish, the shape of that lure can be used to identify species. But unlike the frogfish the lure is located between their mouth (which near the bottom of the body and is very small) and a pointed rostrum that extends from the top of their head like a battering ram. This lure is extended to lure not fish swimming above, as with the frogfish, but small creatures in and on the sand. Because of this they do not call the lure an illicium but a esca. These are strange looking fish.

Hoese and Moore list four different species and indicate there are at least three others in the Gulf of Mexico. Most are associated with the continental shelf of the Gulf and not inland where we might see them snorkeling around. A couple of species are more associated the continental slope, which drops from the continental shelf to the deep sea. But the Polka-dot batfish (Ogocephalus cubifrons) is reported as being inshore and is the species I have encountered.

Many species are only described as being from the shelf of the Gulf of Mexico and no other oceans. Some of them are even more restricted to either the eastern or western Gulf. This all suggests that batfish do have biogeographic barriers of some sort restricting their dispersal. Being offshore benthic fish, your first guess would be substrate. Usually in those locations the temperature and salinities are pretty similar but the material on the bottom (rock, shell, sand, canyons, etc.) are not. However, several articles mention that batfish can be found over rocky or sandy bottom2,3,4 and the polka-dot batfish can be found in grassbeds as well2. So, I am not sure what the possible barrier is, but several do have a limited range. The east-west split could very well be the DeSoto Canyon off the coast of Pensacola.

All of that said, it is a very interesting group of fish that for one species you might encounter while out and about snorkeling or diving in the Florida panhandle.

References

1 Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station, TX. Pp. 327.

2 Ogocephalus cubifrons, Polka-dot batfish. 2017. Discover Fishes. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/ogcocephalus-cubifrons/.

3 The Red-lipped Batfish. 2014. Ashland Vertebrate Biology. Ashland University, Ohio. http://ashlandvertbio.blogspot.com/2014/12/the-red-lipped-batfish.html.

4 Cocos Batfish, Ogocephalus porrectus. 2015. Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. https://biogeodb.stri.si.edu/sftep/en/thefishes/species/777.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 10, 2021

Most people would agree that this is one of the best times of the year. Christmas brings great music, great cooking, great family gatherings, and… great lights. The lighting of Christmas is one of the more beautiful parts of these celebrations and as I thought about Christmas and writing about nature I thought of those lights.

There is nothing like Christmas lights on a tree.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

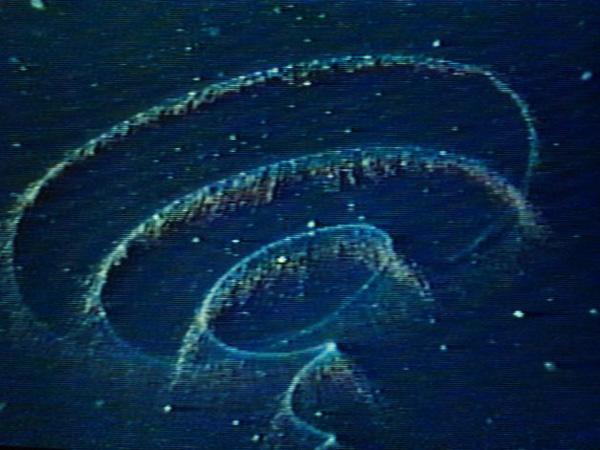

Nature can produce beautiful lights as well. Mostly found in the ocean – “phosphorus”, as many called it when I was growing up here, is a beautiful spectacle. It is hard to see with our artificial lights but in the warmer months of summer at locations far from the artificial lights of people, the sea glows a blue-green color that is amazing. Many see this light as sparkles in the water as the waves roll by. Others see it as a stream of light as a fish, or something else, moves around. In the right conditions, you can see your footprints glow as you step in the wet sand. I remember diving at night under the Bob Sikes Bridge once in the 1970s when the bridge, and all of the divers, were aglow. It was beautiful. This phenomena have amazed scientists for centuries and trying to understand how it is produced was a quest for many.

The term phosphorescence actually means using light to emit light. Turns out that is not what is happening in this case. Scientists found that some creatures posses a group of molecules known as luciferins. The term lucifer means “producing light” or “morning star” and seemed an appropriate name for this group of molecules. When luciferin is oxidized, the transfer of an electron emits a “cool light” – usually blue-green in color. Cool meaning that less than 20% of the emitted light is lost as heat. There is a catalytic enzyme known as luciferase that can increase the speed of this chemical reaction and produce bright light in seconds. Since this light is produced by a chemical reaction it was called “chemiluminescence”. However, since this reaction is produced and controlled by living organisms is more widely known as “bioluminescence”. It is not phosphorescence.

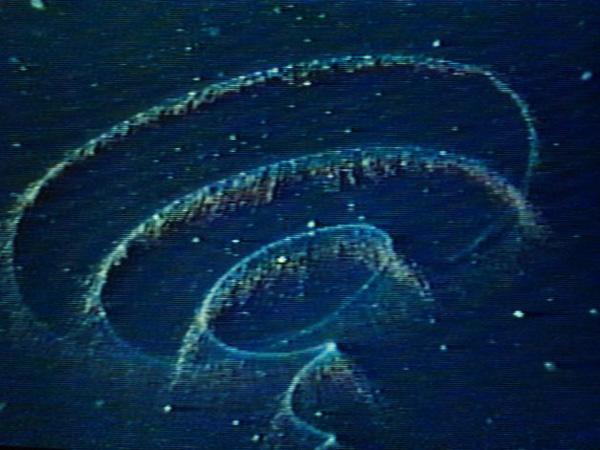

Bioluminescence in the sea.

Photo: North Carolina Sea Grant

There are many creatures that produce bioluminescence. The famous fireflies are one, but most live in the sea. The “phosphorus” we are used to seeing is produced by small single celled plants in a group known as dinoflagellates. When disturbed they emit blue-green light as a flash and then a slow dim. Fish swimming past, waves crashing on the beach, or boat and propeller pushing through the water will disturb them. The warmer the sea, the more dinoflagellates there are, the more amazing the light show is. There are lagoons in the tropical parts of the world where these small plants are trapped due to a small opening in and out of the lagoon. The entire lagoon can light up when the conditions are right.

Noctiluca are one of the dinoflagellates that produce bioluminescence.

Photo: University of New Hampshire.

But it does not stop with dinoflagellates. As you descend into the deep ocean the bioluminescence becomes even more spectacular. All sorts of creatures from jellyfish to squid, to fish, to even fungus and bacteria illuminate. Some species of luminescent marine animals do not produce the light themselves but rather harbor luminescent bacteria on the skin or specially designed skim pockets to hold them. Though blue-green is the dominant color, yellows, oranges, and reds have been produced. It has been suggested that blue-green is much easier to see in the deep so reds and oranges are less likely. That said, it is believed that some marine creatures will produce those colors to assist in capturing prey. They can see the red light, but their prey cannot.

The magical lights of the deep sea.

Photo: NOAA

Either way the illumination of the ocean, like the Christmas illumination of our streets and homes, is beautiful and amazing thing. As you admire the lights on the neighborhood home, find some short videos of bioluminescence online and enjoy the show. Happy Holidays everyone.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 10, 2021

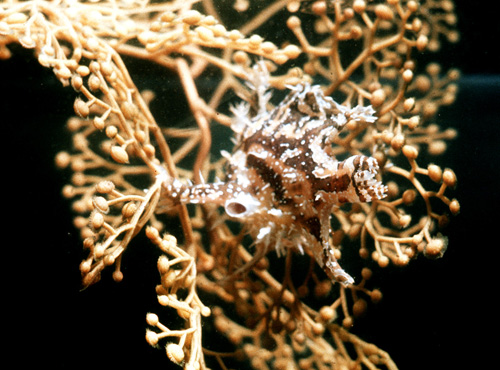

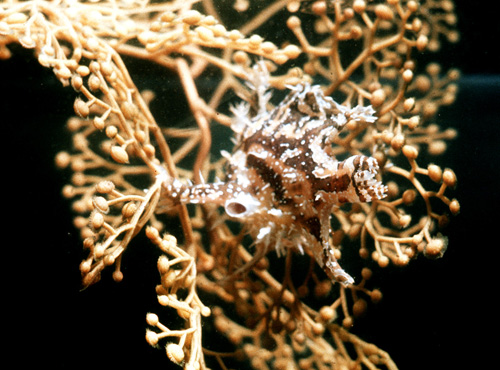

Hoese and Moore1 describes members of the frogfish family as “grotesque”. Well… maybe. I am not sure I would call them grotesque, but they are sort of gelatinous blobs with reduced or missing scales. They feel sort of “mushy”. They have broad shaped fins and a free dorsal spine that serves as a “fishing rod and lure” called the illicium. Maybe they are a little grotesque…maybe.

Being round with broad fins, this is a very slow swimming fish, if you can call how they move swimming. So, to survive, they must blend in with the environment to avoid predators and wait for their prey to come within range before pouncing on them. The illicium lures prey to within range and their “gulp” is like a vacuum cleaner sucking food out of the water.

The family name for the group is Antennariidae, which is appropriate being they have that fishing lure, and is one of the few fish families whose gill opens are behind the pectoral fin. There are 48 species of frogfish found worldwide and most are tropical and subtropical2. Hoese and Moore1 indicate there are three species found in the Gulf of Mexico and all three can be found along the Florida panhandle.

The most commonly encountered frogfish in our area is the Sargassum fish (Histro histro). This small six-inch fish blends in perfectly with the sargassum mats that float in close to shore. Using its fins to brace itself in the seaweed, this fish uses its illicium to attract a variety of small prey that live in the sargassum community. As the sargassum mats are blown close to shore the sargassum fish will leave and move to another mat further out. Finding them on the beach is rare but snorkeling out to a mat just offshore with a small hand net, you might be able to find one by scooping up some sargassum and taking a look.

This sargassum fish is well camelflouged within this mat of sargassum weed.

Photo: Florda Museum of Natural History

The Singlespot Frogfish (Antennarius radiosus) is even smaller at three inches and is found on hard habitats of the middle continental shelf offshore, but occasionally is found along the coastline.

The Splitlure Frogfish (Phrynelox scaber) is five inches in length and not as common on our shelf as the singlespot frogfish. Those that have been found off our coast were further offshore.

The Florida Museum of Natural History includes the Striated Frogfish (Antennarius striatus) as a Gulf species and resident of panhandle waters3.

The distribution of this group is pretty wide throughout the tropical and subtropical waters of the Atlantic Ocean and beyond – suggesting few geographic barriers to dispersal. The sargassum fish, of course, is restricted where sargassum is found – but sargassum is found in a lot of places. The singlespot frogfish seems to have a more restricted home range found in Bermuda, the Atlantic coast of Georgia and Florida, and the Gulf of Mexico. Hoese and Moore does not report this fish in other parts of the Caribbean as the others are1.

They may be grotesque to some, but to others it is an amazing group of fish, much fun in an aquarium, and exciting to find when snorkeling or diving.

1 Hoese H.D., Moore R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M University. College Station TX. Pp. 327.

2 Family Antennariidae – Frogfish. 2012. FishBase. https://www.fishbase.de/summary/FamilySummary.php?ID=192.

3 Antennarius striatus. 2017. Discover Fishes. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/antennarius-striatus/.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 29, 2021

Sargassum washed ashore after a storm on Pensacola Beach. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

I am sure it drives the tourists a little crazy. After daydreaming all year of a week relaxing at the beach, they arrive and find the shores covered in leggy brown seaweed for long stretches. It floats in the shallow water, tickling legs and causing a mild panic—was that a fish? A jellyfish? A shark? Then, of course, high tide washes the seaweed up and strands it at the wrack line, shattering the vision of dreamy white sand beaches.

But for those visitors—and locals—willing to take a closer look, the brown algae known as sargassum is one of the most fascinating organisms in the sea. The next time you are at the beach, pick some up and turn it over in your hands. Sargassum is characterized by its bushy, highly branched stems with numerous leafy blades and berry-like, gas-filled structures. The tiny air sacs serve as flotation devices to keep the algae from sinking. This unique adaptation allows it to fulfill a niche at the top of the water column, instead of growing at the bottom or on another organism.

The sargassum fish blends incredibly well into its home within sargassum mats. It uses handlike pectoral fins to move around. Photo credit: Reef Builders

Sargassum tends to accumulate into large mats that drift through the water in response to wind and currents. These drifting mats create a pelagic habitat that attracts up to 70 species of marine animals. Several of these organisms are adapted specifically to life within the sargassum, reaching full growth at miniature sizes and camouflaged in shape, pattern, and color to blend in. These very specialized fauna include the sargassum crab, the sargassum shrimp, sargassum flatworm, sargassum nudibranch, sargassum anemone, and the sargassum fish! The sargassum fish (Histrio histrio) is in the toadfish family, a group of slow-moving reef fish that pick their way through coral and algae by using their pectoral fins like hands. Sea turtle hatchlings will spend their early years feeding and resting within the relative safety of large mid-ocean sargassum mats.

The small air-filled sacs of sargassum allow it to float on the surface, becoming the basis of a teeming ecosystem. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Over time the air sacs lose buoyancy and the sargassum sinks, providing an important source of food for bottom-dwelling creatures. If washed ashore, many of the animals abandon the sargassum or risk drying out and dying.

In general, most of the larger, familiar seaweeds like sargassum are brown algae. Brown algae (including kelp and rockweed) have colors ranging from brown to brownish yellow-green. These darker colors result from the brown pigment fucoxanthin, which masks the green color of chlorophyll. Extractions from brown algae are commonly used in lotions and even heartburn medication!